William James Bennett, “View of South Street, from Maiden Lane, New York City,” ca. 1827, via Metropolitan Museum of New York

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

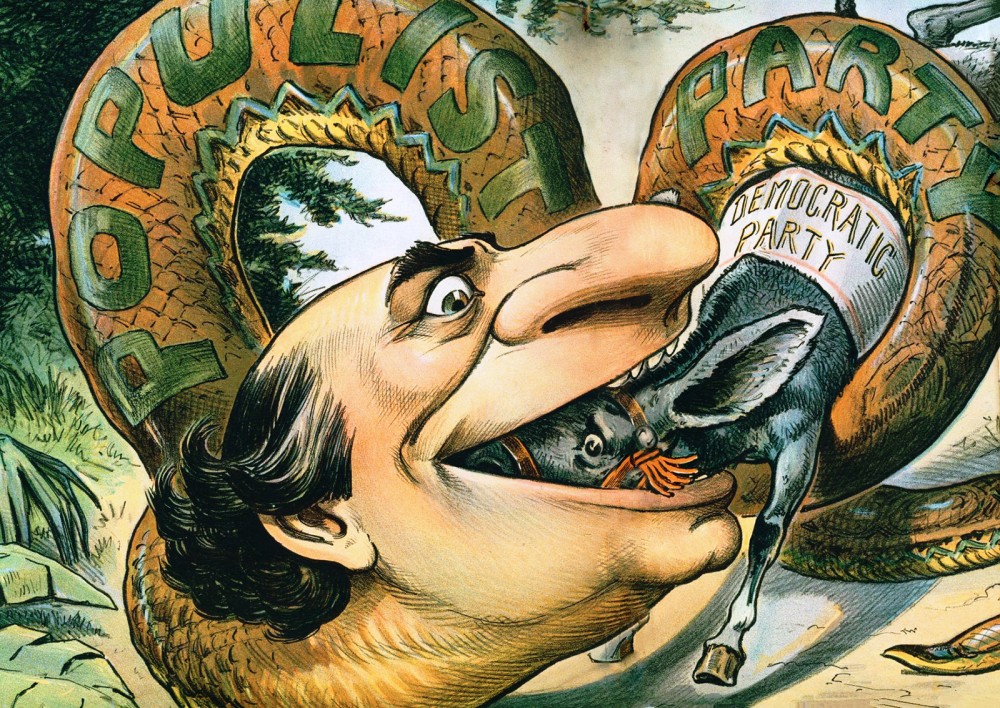

In the early years of the nineteenth century, Americans’ endless commercial ambition—what one Baltimore paper in 1815 called an “almost universal ambition to get forward”—remade the nation. ((Hezekiah Niles, Dec. 2, 1815, Niles’ Weekly Register, Volume 9 (Baltimore: 1816), 238.)) Between the Revolution and the Civil War, an old subsistence world died and a new more-commercial nation was born. Americans integrated the technologies of the Industrial Revolution into a new commercial economy. Steam power, the technology that moved steamboats and railroads, fueled the rise of American industry by powering mills and sparking new national transportation networks. A “market revolution” was busy remaking the nation.

The revolution reverberated across the country. More and more farmers grew crops for profit, not self-sufficiency. Vast factories and cities arose in the North. Enormous fortunes materialized. A new middle class ballooned. And as more men and women worked in the cash economy, they were freed from the bound dependence of servitude. But there were costs to this revolution. As northern textile factories boomed, the demand for southern cotton swelled and the institution of American slavery accelerated. Northern subsistence farmers became laborers bound to the whims of markets and bosses. The market revolution sparked not only explosive economic growth and new personal wealth but also devastating depressions—“panics”—and a growing lower class of property-less workers. Many Americans labored for low wages and became trapped in endless cycles of poverty. Some workers—often immigrant women—worked thirteen hours a day, six days a week. Others labored in slavery. Massive northern textile mills turned southern cotton into cheap cloth. And although northern states washed their hands of slavery, their factories fueled the demand for slave-grown southern cotton that ensured the profitability and continued existence of the American slave system. And so, as the economy advanced, the market revolution wrenched the United States in new directions as it became a nation of free labor and slavery, of wealth and inequality, and of endless promise and untold perils.

II. Early Republic Economic Development

The growth of the American economy reshaped American life in the decades before the Civil War. Americans increasingly produced goods for sale, not for consumption. With a larger exchange network connected by improved transportations, the introduction of labor-saving technology, and the separation of the public and domestic spheres, the market revolution fulfilled the revolutionary generation’s expectations of progress but introduced troubling new trends. Class conflict, child labor, accelerated immigration, and the expansion of slavery followed. These strains required new family arrangements and forged new urban cultures.

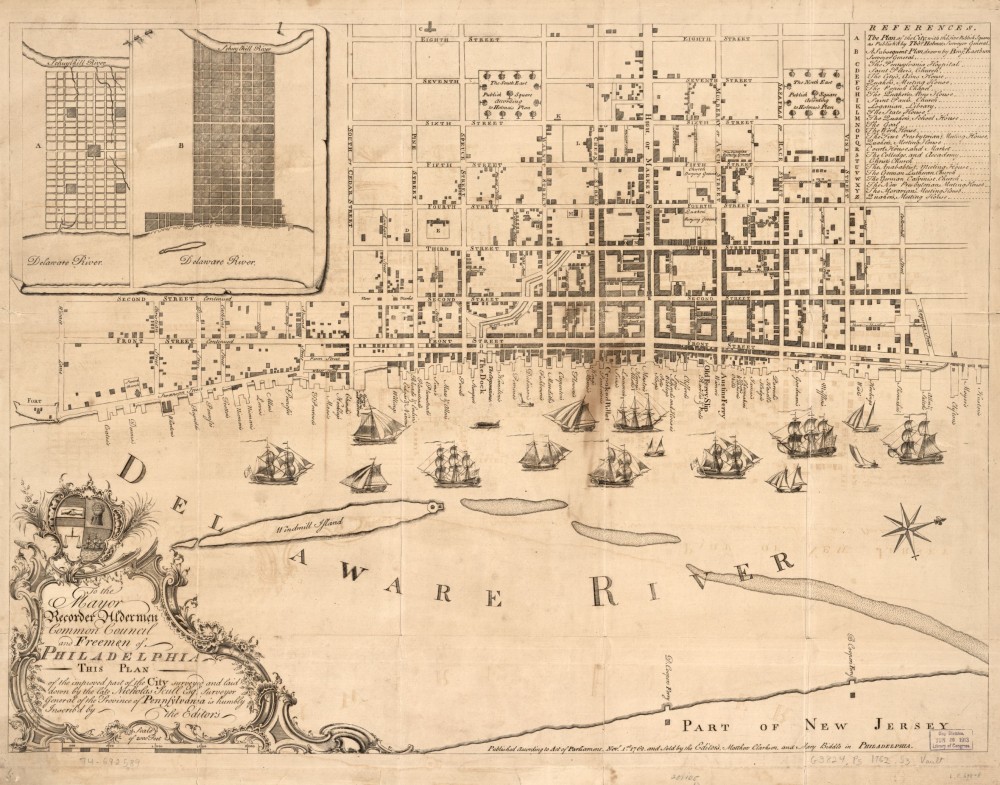

American commerce had proceeded haltingly during the eighteenth century. American farmers increasingly exported foodstuffs to Europe as the French Revolutionary Wars devastated the continent between 1793 and 1815. America’s exports rose in value from $20.2 million in 1790 to $108.3 million by 1807. ((Douglass C. North, Economic Growth in the United States, 1790-1860 (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1961), 25.)) But while exports rose, exorbitant internal transportation costs hindered substantial economic development within the United States. In 1816, for instance, $9 could move one ton of goods across the Atlantic Ocean, but only 30 miles across land. An 1816 Senate Committee Report lamented that “the price of land carriage is too great” to allow the profitable production of American manufactures. But in the wake of the War of 1812, Americans rushed to build a new national infrastructure, new networks of roads, canals, and railroads. In his 1815 annual message to Congress, President James Madison stressed “the great importance of establishing throughout our country the roads and canals which can best be executed under national authority.” ((James Madison, Annual Message to Congress, December 5, 1815.)) State governments continued to sponsor the greatest improvements in American transportation, but the federal government’s annual expenditures on internal improvements climbed to a yearly average of $1,323,000 by Andrew Jackson’s presidency. ((William L. Garrison and David M. Levinson, The Transportation Experience: Policy, Planning, and Deployment (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 51.)).

Clyde Osmer DeLand, “The First Locomotive. Aug. 8th, 1829. Trial Trip of the “Stourbridge Lion,” 1916, via Library of Congress.

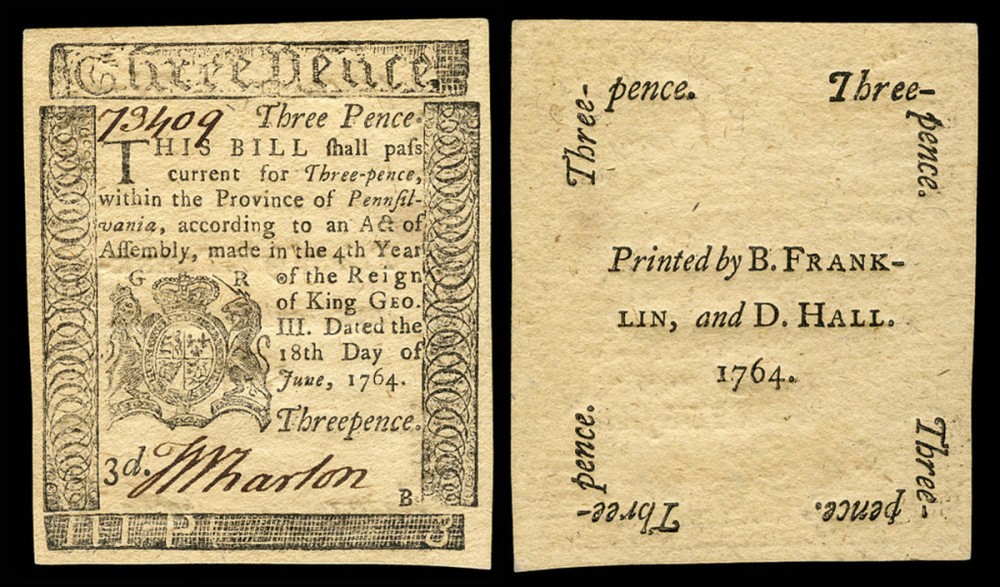

State legislatures meanwhile pumped capital into the economy by chartering banks and the number of state-chartered banks skyrocketed from 1 in 1783, 266 in 1820, 702 in 1840, to 1,371 in 1860. ((Warren E. Weber, “Early State Banks in the United States: How Many Were There and When Did They Exist?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Quarterly Review, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Sept. 2006): 28-40.)) European capital also helped to build American infrastructure. By 1844, one British traveler declared that “the prosperity of America, her railroads, canals, steam navigation, and banks, are the fruit of English capital.” ((John Robert Godley, Letters from America (J. Murray, 1844), 267.))

Economic growth, however, proceeded unevenly. Depressions devastated the economy in 1819, 1837, and 1857. Each followed rampant speculation—bubbles—in various commodities: land in 1819, land and slaves in 1837, and railroad bonds in 1857. The spread of paper currency untethered the economy from physical signifiers of wealth familiar to the colonial generation – namely land. Counterfeit bills were endemic during this early period of banking, as some individuals sought their own way to capitalize on the nation’s quest for wealth. With so many fake bills circulating, Americans were constantly on the lookout for the “confidence man” and other deceptive characters in the urban landscape. Prostitutes and con men could look like regular honest Americans. Advice literature offered young men and women strategies for avoiding hypocrisy in an attempt to restore the social fiber together. Intimacy in the domestic sphere became more important as duplicity proliferated in the public sphere. Fear of the confidence man, counterfeit bills, and a pending bust created anxiety over the foundation of the capitalist economy. But Americans refused to blame the logic of their new commercial system for these depressions. Instead, they kept pushing “to get forward.”

The so-called “Transportation Revolution” opened for Americans the vast lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. In 1810, for instance, before the rapid explosion of American infrastructure, Margaret Dwight left New Haven, Connecticut, in a wagon headed for Ohio Territory. Her trip was less than 500 miles but took six full weeks to complete. The journey was a terrible ordeal, she said. The roads were “so rocky & so gullied as to be almost impassable.” ((Margaret Van Horn Dwight, A Journey to Ohio in 1810, Max Farrand, ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1912), 13.)) Ten days into the journey, at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Dwight said “it appeared to me that we had come to the end of the habitable part of the globe.” She finally concluded that “the reason so few are willing to return from the Western country, is not that the country is so good, but because the journey is so bad.” ((Margaret Van Horn Dwight, A Journey to Ohio in 1810, Max Farrand, ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1912), 37.)) Nineteen years later, in 1829, English traveler Frances Trollope made the reverse journey across the Allegheny Mountains from Cincinnati to the east coast. At Wheeling, Virginia, her coach encountered the National Road, the first federally funded interstate infrastructure project. The road was smooth and her journey across the Alleghenies was a scenic delight. “I really can hardly conceive a higher enjoyment than a botanical tour among the Alleghany Mountains,” she declared. The ninety miles of National Road was to her “a garden.” ((Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, Vol. 1 (London: Whittaker, Treacher & Co., 1832), 274.))

Engraving based on W.H. Bartlett, “Lockport, Erie Canal,” 1839, via Wikimedia.

If the two decades between Margaret Dwight’s and Frances Trollope’s journeys transformed the young nation, the pace of change only accelerated in the following years. If a transportation revolution began with improved road networks, it soon incorporated even greater improvements in the ways people and goods moved across the landscape.

New York State completed the Erie Canal in 1825. The 350 mile-long manmade waterway linked the Great Lakes with the Hudson River—and thereby to the Atlantic Ocean. Soon crops grown in the Great Lakes region were carried by water to eastern cities, and goods from emerging eastern factories made the reverse journey to midwestern farmers. The success of New York’s “artificial river” launched a canal-building boom. By 1840 Ohio created two navigable, all-water links from Lake Erie to the Ohio River.

Robert Fulton established the first commercial steam boat service up and down the Hudson River in New York in 1807. Soon thereafter steamboats filled the waters of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Downstream-only routes became watery two-way highways. By 1830, more than 200 steamboats moved up and down western rivers.

The United States’ first long-distance rail line launched from Maryland in 1827. Baltimore’s city government and the state government of Maryland provided half the start-up funds for the new Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Rail Road Company. The B&O’s founders imagined the line as a means to funnel the agricultural products of the trans-Appalachian West to an outlet on the Chesapeake Bay. Similar motivations led citizens in Philadelphia, Boston, New York City, and Charleston, South Carolina to launch their own rail lines. State and local governments provided the means for the bulk of this initial wave of railroad construction, but economic collapse following the Panic of 1837 made governments wary of such investments. Government supports continued throughout the century, but decades later the public origins of railroads were all but forgotten and the railroad corporation became the most visible embodiment of corporate capitalism.

By 1860 Americans laid more than 30,000 miles of railroads. ((Cathy Matson, Risky Business: Winning and Losing in the Early American Economy, 1780-1850 (Library Company of Philadelphia: 2003), 29.)) The ensuing web of rail, roads, and canals meant that few farmers in the Northeast or Midwest had trouble getting goods to urban markets. Railroad development was slower in the South, but there a combination of rail lines and navigable rivers meant that few cotton planters struggled to transport their products to textile mills in the Northeast and in England.

Such internal improvements not only spread goods, they spread information. The “transportation revolution” was followed by a “communications revolution.” The telegraph redefined the limits of human communication. By 1843 Samuel Morse persuaded Congress to fund a forty-mile telegraph line stretching from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore. Within a few short years, during the Mexican-American War, telegraph lines carried news of battlefield events to eastern newspapers within days, in stark contrast to the War of 1812, when the Battle of New Orleans took place nearly two full weeks after Britain and the United States had signed a peace treaty.

The consequences of the transportation and communication revolutions reshaped the lives of Americans. Farmers who previously produced crops mostly for their own family now turned to the market. They earned cash for what they had previously consumed; they purchased the goods they had previously made or went without. Market-based farmers soon accessed credit through eastern banks, which provided them with both the opportunity to expand their enterprise but left them prone before the risk of catastrophic failure wrought by distant and impersonal market forces. In the Northeast and Midwest, where farm labor was ever in short supply, ambitious farmers invested in new technologies that promised to increase the productivity of the limited labor supply. The years between 1815 and 1850 witnessed an explosion of patents on agricultural technologies. The most famous of these, perhaps, was Cyrus McCormick’s horse-drawn mechanical reaper, which partially mechanized wheat harvesting, and John Deere’s steel-bladed plough, which more easily allowed for the conversion of unbroken ground into fertile farmland.

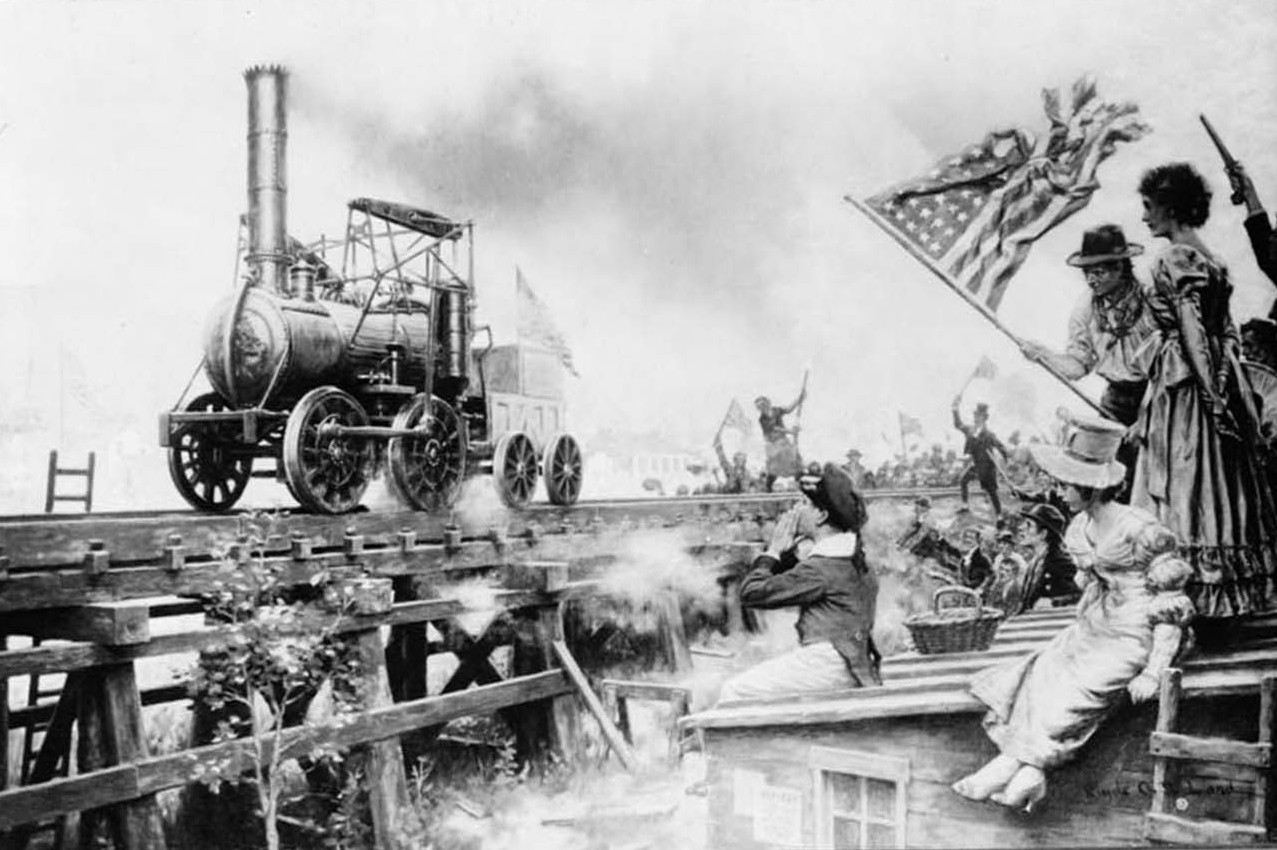

A. Janicke & Co., “Our City, (St. Louis, Mo.),” 1859, via Library of Congress.

Most visibly, the market revolution encouraged the growth of cities and reshaped the lives of urban workers. In 1820, only two cities in the United States—New York and Philadelphia—had over 100,000 inhabitants. By 1850, six American cities met that threshold, including Chicago, which had been founded fewer than two decades earlier. ((Leonard P. Curry, The Corporate City: The American City as a Political Entity, 1800-1850 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing, 1997), 46.)) New technology and infrastructure paved the way for such growth. The Erie Canal captured the bulk of the trade emerging from the Great Lakes region, securing New York City’s position as the nation’s largest and most economically important city. The steamboat turned St. Louis and Cincinnati into centers of trade, and Chicago rose as it became the railroad hub of the western Great Lakes and Great Plains regions. The geographic center of the nation shifted westward. The development of steam power and the exploitation of Pennsylvania coalfields shifted the locus of American manufacturing. By the 1830s, for instance, New England was losing its competitive advantage as new sources and locations of power opened up in other regions.

Meanwhile, the cash economy eclipsed the old, local, informal systems of barter and trade. Income became the measure of economic worth. Productivity and efficiencies paled before the measure of income. Cash facilitated new impersonal economic relationships and formalized new means of production. Young workers might simply earn wages, for instance, rather than receiving room and board and training as part of apprenticeships. Moreover, a new form of economic organization appeared: the business corporation.

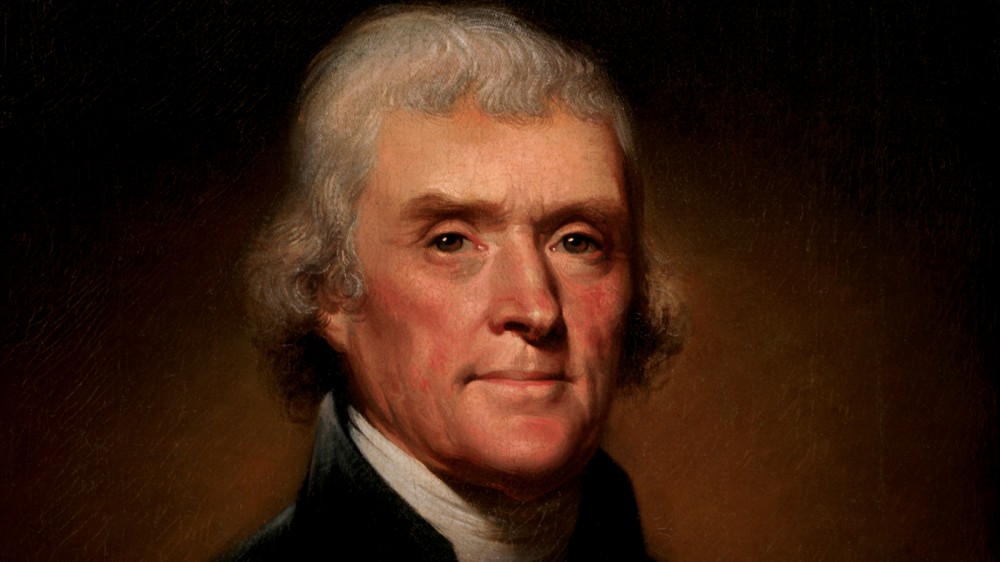

To protect the fortunes and liabilities of entrepreneurs who invested in early industrial endeavors, states offered the privileges of incorporation. A corporate charter allowed investors and directors to avoid personal liability for company debts. The legal status of incorporation had been designed to confer privileges to organizations embarking upon expensive projects explicitly designed for the public good, such as universities, municipalities, and major public works projects. The business corporation was something new. Many Americans distrusted these new, impersonal business organizations whose officers lacked personal responsibility while nevertheless carrying legal rights. Many wanted limits. Thomas Jefferson himself wrote in 1816 that “I hope we shall crush in its birth the aristocracy of our monied corporations which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength, and bid defiance to the laws of our country.” ((Jefferson to George Logan, 12 Nov 1816 Works of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Paul Leicester Ford, Federal Edition, 12 vols. (New York: 1904), 12:43)) But in Dartmouth v. Woodward (1819) the Supreme Court upheld the rights of private corporations when it denied the government of New Hampshire’s attempt to reorganize Dartmouth College on behalf of the common good. Still, suspicions remained. A group of journeymen cordwainers in New Jersey publically declared in 1835 that they “entirely disapprov[ed] of the incorporation of Companies, for carrying on manual mechanical business, inasmuch as we believe their tendency is to eventuate and produce monopolies, thereby crippling the energies of individual enterprise.” ((Quoted in Michael Zakim and Gary John Kornblith, eds., Capitalism Takes Command: The Social Transformation of Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 158.))

III. The Decline of Northern Slavery and the Rise of the Cotton Kingdom

The market revolution economic depended upon not just free-labor factories in the north, but slave-labor plantations in the south. By 1832, textile companies made up 88 out of 106 American corporations valued at over $100,000. ((Philip Scranton, Proprietary Capitalism: The Textile Manufacture at Philadelphia, 800-1885 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 12.)) These textile mills, worked by free labor, nevertheless depended upon southern cotton and the vast new market economy spurred the expansion of the plantation South.

By the early-nineteenth century, states north of the Mason-Dixon Line had taken steps to abolish slavery. Vermont included abolition as a provision of its 1777 state constitution. Pennsylvania’s emancipation act of 1780 stipulated that freed children serve an indenture term of twenty-eight years. Gradualism prompted emancipation but defended the interests of Northern masters and controlled still another generation of black Americans. In 1804 New Jersey became the last of the northern states to adopt gradual emancipation plans. There was no immediate moment of jubilee, as many northern states only promised to liberate future children born to enslaved mothers. Such laws also stipulated that such children remain in indentured servitude to their mother’s master in order to compensate the slaveholder’s loss. James Mars, a young man indentured under this system in Connecticut, risked being thrown in jail when he protested the arrangement that kept him bound to his mother’s master until age twenty five. ((Robert J. Cottrol, ed., From African to Yankee: Narratives of Slavery and Freedom in Antebellum New England (Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe, 1998), 62.))

Quicker routes to freedom included escape or direct emancipation by masters. But escape was dangerous and voluntary manumission rare. Congress, for instance, made the harboring of a fugitive slave a federal crime by 1793. Hopes for manumission were even slimmer, as few Northern slaveholders emancipated their own slaves. For example, roughly one-fifth of the white families in New York City owned slaves and yet fewer than 80 slaveholders in the city voluntarily manumitted slaves between 1783 and 1800. By 1830, census data suggests that at least 3,500 people were still enslaved in the North. Elderly Connecticut slaves remained in bondage as late as 1848 and in New Jersey until after the Civil War. ((The 1830 census enumerates 3,568 enslaved people in the northern states (designation of Northern States in 1830 includes Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont). 1830 US Census data taken from Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. Accessible online: http://www.nhgis.org; David Menschel, “Abolition Without Deliverance: The Law of Connecticut Slavery 1784-1848,” Yale Law Journal. Vol. 111 Is. 1, (Oct 2001), 191; James J. Gigantino II, The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey 1775-1865 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 248.))

Emancipation proceeded slowly, but proceeded nonetheless. A free black population of fewer than 60,000 in 1790 increased to more than 186,000 by 1810. Growing free black communities fought for their civil rights. In a number of New England locales, free African Americans could vote and send their children to public schools. Most northern states granted black citizens property rights and trial by jury. African Americans owned land and businesses, founded mutual aid societies, established churches, promoted education, developed print culture, and voted.

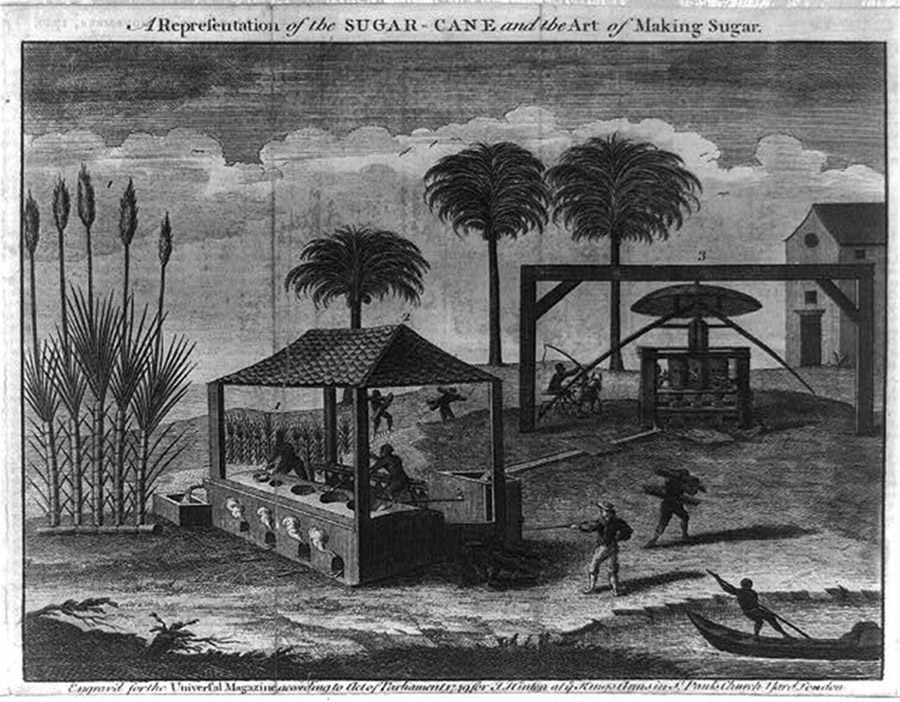

Nationally, however, the slave population continued to grow, from less than 700,000 in 1790 to more than 1.5 million unfree persons by 1820. ((Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. Accessible online: http://www.nhgis.org.)) The growth of abolition in the north and the acceleration of slavery in the South created growing divisions between North and South. Slavery declined in the North, but became more deeply entrenched in the South, owing in great part to the development of a new profitable staple crop: cotton. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, a simple hand-cranked device designed to mechanically remove sticky green seeds from short staple cotton, allowed southern planters to dramatically expand cotton production for the national and international markets. Technological innovations elsewhere—water-powered textile factories in England and the American northeast, which could rapidly turn raw cotton into cloth—increased demand for southern cotton and encouraged white Southerners to expand cultivation farther west, to Mississippi River and beyond. Slavery’s profitability had lagged in tobacco planting, but cotton gave it new life. Eager cotton planters invested their new profits in new slaves.

The cotton boom fueled speculation in slavery. Many slave owners leveraged potential profits into loans used to purchase ever increasing numbers of slaves. For example, one 1840 Louisiana Courier ad warned “it is very difficult now to find persons willing to buy slaves from Mississippi or Alabama on account of the fears entertained that such property may be already mortgaged to the banks of the above named states.” ((Louisiana Courier, 12 Feb 1840.))

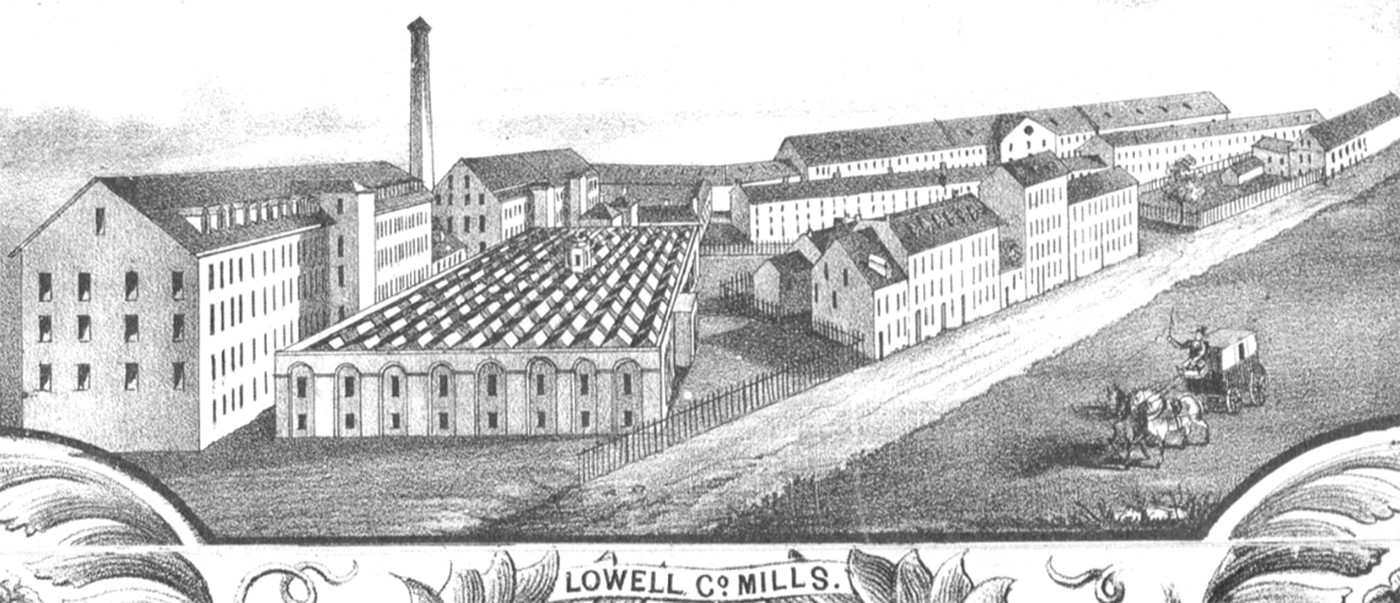

Sidney & Neff, Detail from “Plan of the City of Lowell, Massachusetts,” 1850, via Wikimedia Commons.

New national and international markets fueled the plantation boom. American cotton exports rose from 150,000 bales in 1815 to 4,541,000 bales in 1859. The Census Bureau’s 1860 Census of Manufactures stated that “the manufacture of cotton constitutes the most striking feature of the industrial history of the last fifty years.” ((United States Census Office 8th Census 1860 and James Madison Edmunds, Manufactures of the United States in 1860: Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census, Under the Direction of the Secretary of the Interior (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1865).)) Slave owners shipped their cotton north to textile manufacturers and to northern financers for overseas shipments. Northern insurance brokers and exporters in the Northeast profited greatly.

While the United States ended its legal participation in the global slave trade in 1808, slave traders moved 1,000,000 slaves from the tobacco-producing Upper South to cotton fields in the Lower South between 1790 and 1860. ((Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 168-169.)) This harrowing trade in human flesh supported middle-class occupations North and South: bankers, doctors, lawyers, insurance brokers, and shipping agents all profited. And of course it facilitated the expansion of northeastern textile mills.

IV. Changes in Labor Organization

While industrialization bypassed much of the American South, southern cotton production nevertheless nurtured industrialization in the Northeast and Midwest. The drive to produce cloth transformed the American system of labor. In the early republic, laborers in manufacturing might typically have been expected to work at every stage of production. But a new system, “piece work,” divided much of production into discrete steps performed by different workers. In this new system, merchants or investors sent or “put-out” materials to individuals and families to complete at home. These independent laborers then turned over the partially finished goods to the owner to be given to another laborer to finish.

As early as the 1790s, however, merchants in New England began experimenting with machines to replace the “putting-out” system. To effect this transition, merchants and factory owners relied on the theft of British technological knowledge to build the machines they needed. In 1789, for instance, a textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island contracted twenty-one-year-old British immigrant Samuel Slater to build a yarn-spinning machine and then a carding machine because he had apprenticed in an English mill and was familiar with English machinery. The fruits of American industrial espionage peaked in 1813 when Francis Cabot Lowell and Paul Moody recreated the powered loom used in the mills of Manchester, England. Lowell had spent two years in Britain observing and touring mills in England. He committed the design of the powered loom to memory so that, no matter how many times British customs officials searched his luggage, he could smuggle England’s industrial know-how into New England.

Lowell’s contribution to American industrialism was not only technological, it was organizational. He helped reorganize and centralize the American manufacturing process. A new approach, the Waltham-Lowell System, created the textile mill that defined antebellum New England and American industrialism before the Civil War. The modern American textile mill was fully realized in the planned mill town of Lowell in 1821, four years after Lowell himself died. Powered by the Merrimack River in northern Massachusetts and operated by local farm girls, the mills of Lowell centralized the process of textile manufacturing under one roof. The modern American factory was born. Soon ten thousand workers labored in Lowell alone. Sarah Rice, who worked at the nearby Millbury factory, found it “a noisy place” that was “more confined than I like to be.” ((Sarah “Sally” Rice to her father, 23 Feb 1845, published in The New England Mill Village, 1790-1860 (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1982), 390.)) Working conditions were harsh for the many desperate “mill girls” who operated the factories relentlessly from sun-up to sun-down. One worker complained that “a large class of females are, and have been, destined to a state of servitude.” ((Factory Tracts. Factory Life As It Is, Number One, [(Lowell, MA, 1845)].)) Women struck. They lobbied for better working hours. But the lure of wages was too much. As another worker noted, “very many Ladies…have given up millinery, dressmaking & school keeping for work in the mill.” ((Malenda M. Edwards to Sabrina Bennett, 4 Apr 1839, quoted in Thomas Dublin, ed., Farm to Factory Women’s Letters, 1830-1860 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 74.)) With a large supply of eager workers, Lowell’s vision brought a rush of capital and entrepreneurs into New England and the first manufacturing boom in the new republic.

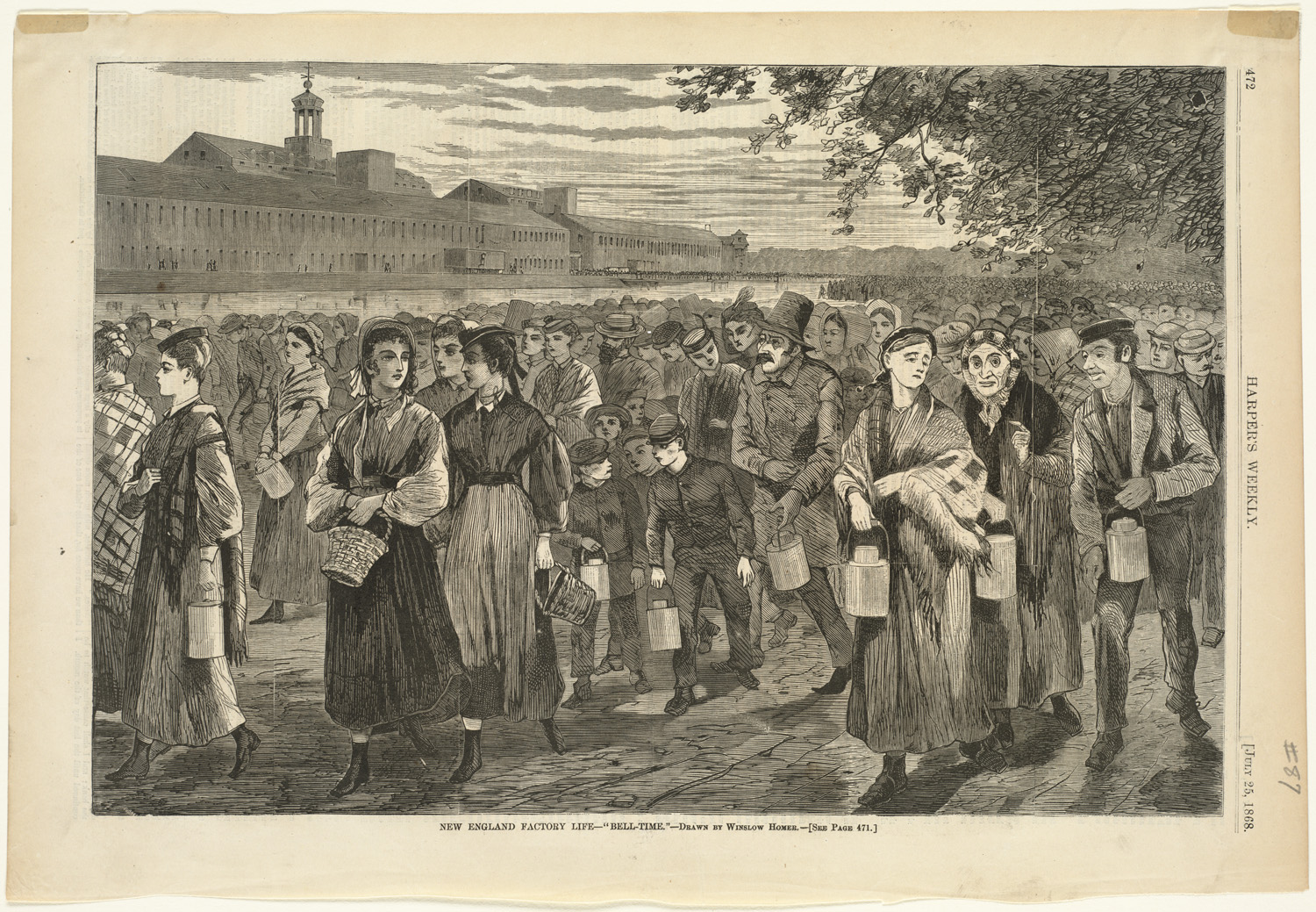

Winslow Homer, “Bell-Time,” Harper’s Weekly vol. XII (July 1868): p. 472, via Wikimedia.

The market revolution shook other industries as well. Craftsmen began to understand that new markets increased the demand for their products. Some shoemakers, for instance, abandoned the traditional method of producing custom-built shoes at their home workshop and instead began producing larger quantities of shoes in ready-made sizes to be shipped to urban centers. Manufacturers wanting increased production abandoned the old personal approach of relying upon a single live-in apprentice for labor and instead hired unskilled wage laborers who did not have to be trained in all aspects of making shoes but could simply be assigned a single repeatable aspect of the task. Factories slowly replaced shops. The old paternalistic apprentice system, which involved long-term obligations between apprentice and master, gave way to a more impersonal and more flexible labor system in which unskilled laborers could be hired and fired as the market dictated. A writer in the New York Observer in 1826 complained, “The master no longer lives among his apprentices [and] watches over their moral as well as mechanical improvement.” ((“Apprentices No. 2,” New York Observer October 14, 1826.)) Masters-turned-employers now not only had fewer obligations to their workers, they had a lesser attachment. They no longer shared the bonds of their trade but were subsumed under a new class-based relationships: employers and employees, bosses and workers, capitalists and laborers. On the other hand, workers were freed from the long-term, paternalistic obligations of apprenticeship or the legal subjugation of indentured servitude. They could—theoretically—work when and where they wanted. When men or women made an agreement with an employer to work for wages, they were “left free to apportion among themselves their respective shares, untrammeled…by unwise laws,” as Reverend Alonzo Potter rosily proclaimed in 1840. ((Reverend Alonzo Potter, Political Economy: Its Objects, Uses, and Principles, 1840, 92.)) But while the new labor system was celebrated throughout the northern United States as “free labor,” it was simultaneously lamented by a growing powerless class of laborers.

As the northern United States rushed headlong toward commercialization and an early capitalist economy, many Americans grew uneasy with the growing gap between wealthy businessmen and impoverished wage laborers. Elites like Daniel Webster might defend their wealth and privilege by insisting that all workers could achieve “a career of usefulness and enterprise” if they were “industrious and sober,” but labor activist Seth Luther countered that capitalism created “a cruel system of extraction on the bodies and minds of the producing classes…for no other object than to enable the ‘rich’ to ‘take care of themselves’ while the poor must work or starve.” ((Daniel Webster, “Lecture Before the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge,” in The Writings and Speeches of Daniel Webster: Writings and Speeches Hitherto Uncollected, v. 1. Addresses on Various Occasions, ed. Edward Everett (Little, Brown, 1903); Carl Siracusa, A Mechanical People: Perceptions of the Industrial Order in Massachusetts, 1815-1880 (Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan University Press, 1979), 157.))

Americans embarked upon their industrial revolution with the expectation that all men could start their careers as humble wage workers but later achieve positions of ownership and stability with hard work. Wage work had traditionally been looked-down upon as a state of dependence, suitable only as a temporary waypoint for young men without resources on their path toward the middle class and the economic success necessary to support a wife and children ensconced within the domestic sphere. Children’s magazines – such as Juvenile Miscellany and Parley’s Magazine – glorified the prospect of moving up the economic ladder. This “free labor ideology” provided many Northerners with a keen sense of superiority over the slave economy of the southern states. ((Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men : The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).))

But the commercial economy often failed in its promise of social mobility. Depressions and downturns might destroy businesses and reduce owners to wage work, but even in times of prosperity unskilled workers might perpetually lack good wages and economic security and therefore had to forever depend upon supplemental income from their wives and young children.

Wage workers—a population disproportionately composed of immigrants and poorer Americans—faced low wages, long hours, and dangerous working conditions. Class conflict developed. Instead of the formal inequality of a master-servant contract, employer and employee entered a contract presumably as equals. But hierarchy was evident: employers had financial security and political power; employees faced uncertainty and powerlessness in the workplace. Dependent upon the whims of their employers, some workers turned to strikes and unions to pool their resources. In 1825 a group of journeymen in Boston formed a Carpenters’ Union to protest their inability “to maintain a family at the present time, with the wages which are now usually given.” ((“Notice to House Carpenters in the Country,” Columbian Centinel, 23 Apr 1825.)) Working men organized unions to assert themselves and win both the respect and the resources due to a breadwinner and a citizen.

For the middle-class managers and civic leaders caught between workers and owners, unions enflamed a dangerous antagonism between employers and employees. They countered any claims of inherent class conflict with the ideology of social mobility. Middle-class owners and managers justified their economic privilege as the natural product of superior character traits, including their wide decision-making and hard work. There were not classes of capitalists and laborers in America, they said, there was simply a steady ladder carrying laborers upward into management and ownership. One group of master carpenters denounced their striking journeyman in 1825 with the claim that workers of “industrious and temperate habits, have, in their turn, become thriving and respectable Masters, and the great body of our Mechanics have been enabled to acquire property and respectability, with a just weight and influence in society.” ((John R. Commons, ed., A Documentary History of American Industrial Society (New York: Russell & Russell, 1958), VI: 79.)) In an 1856 speech in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Abraham Lincoln had to assure his audience that the country’s commercial transformation had not reduced American laborers to slavery. Southerners, he said “insist that their slaves are far better off than Northern freemen. What a mistaken view do these men have of Northern labourers! They think that men are always to remain labourers here – but there is no such class. The man who laboured for another last year, this year labours for himself. And next year he will hire others to labour for him.” ((Abraham Lincoln, Speech at Kalamazoo, Michigan, Aug. 27, 1856, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. II (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 364.)) It was this essential belief that undergirded the northern commitment to “free labor” and won the market revolution much widespread acceptance.

V. Changes in Gender Roles and Family Life

In the first half of the nineteenth century, families in the northern United States increasingly participated in the cash economy created by the market revolution. The first stirrings of industrialization shifted work away from the home. These changes transformed Americans’ notions of what constituted work, and therefore shifted what it meant to be an American woman and an American man. As Americans encountered more goods in stores and produced fewer at home, the ability to remove women and children from work determined a family’s class status. This ideal, of course, ignored the reality of women’s work at home and was possible for only the wealthy. The market revolution therefore not only transformed the economy, it changed the nature of the American family. As the market revolution thrust workers into new systems of production, it redefined gender roles. The market integrated families into a new cash economy, and as Americans purchased more goods in stores and produced fewer at home, the activities of the domestic sphere—the idealized realm of women and children—increasingly signified a family’s class status.

Women and children worked to supplement the low wages of many male workers. Around age eleven or twelve, boys could take jobs as office runners or waiters, earning perhaps a dollar a week to support their parents’ incomes. The ideal of an innocent and protected childhood was a privilege for middle- and upper-class families, who might look down upon poor families. Joseph Tuckerman, a Unitarian minister who served poor Bostonians, lamented the lack of discipline and regularity among poor children: “At one hour they are kept at work to procure fuel, or perform some other service; in the next are allowed to go where they will, and to do what they will.” ((Joseph Tuckerman, Mr. Tuckerman’s Eight Semiannual Report in his service as a Minister at Large in Boston (Boston: Gray and Bowen, 1831), 21.)) Prevented from attending school, poor children served instead as economic assets for their destitute families.

Meanwhile, the education received by middle-class children provided a foundation for future economic privilege. As artisans lost control over their trades, young men had a greater incentive to invest time in education to find skilled positions later in life. Formal schooling was especially important for young men who desired apprenticeships in retail or commercial work. Enterprising instructors established schools to assist “young gentlemen preparing for mercantile and other pursuits, who may wish for an education superior to that usually obtained in the common schools, but different from a college education, and better adapted to their particular business,” such as that organized in 1820 by Warren Colburn of Boston. ((Warren Colburn, “Advertisement for Colburn’s school for young gentlemen preparing for mercantile and other pursuits, 19 Sep 1820,” (Boston), Massachusetts Historical Society.)) In response to this need, the Boston School Committee created the English High School (as opposed to the Latin School) that could “give a child an education that shall fit him for active life, and shall serve as a foundation for eminence in his profession, whether Mercantile or Mechanical” beyond that “which our public schools can now furnish.” ((Proceedings of the School Committee, of the Town of Boston, respecting an English Classical School (Boston: The Committee, 1820).))

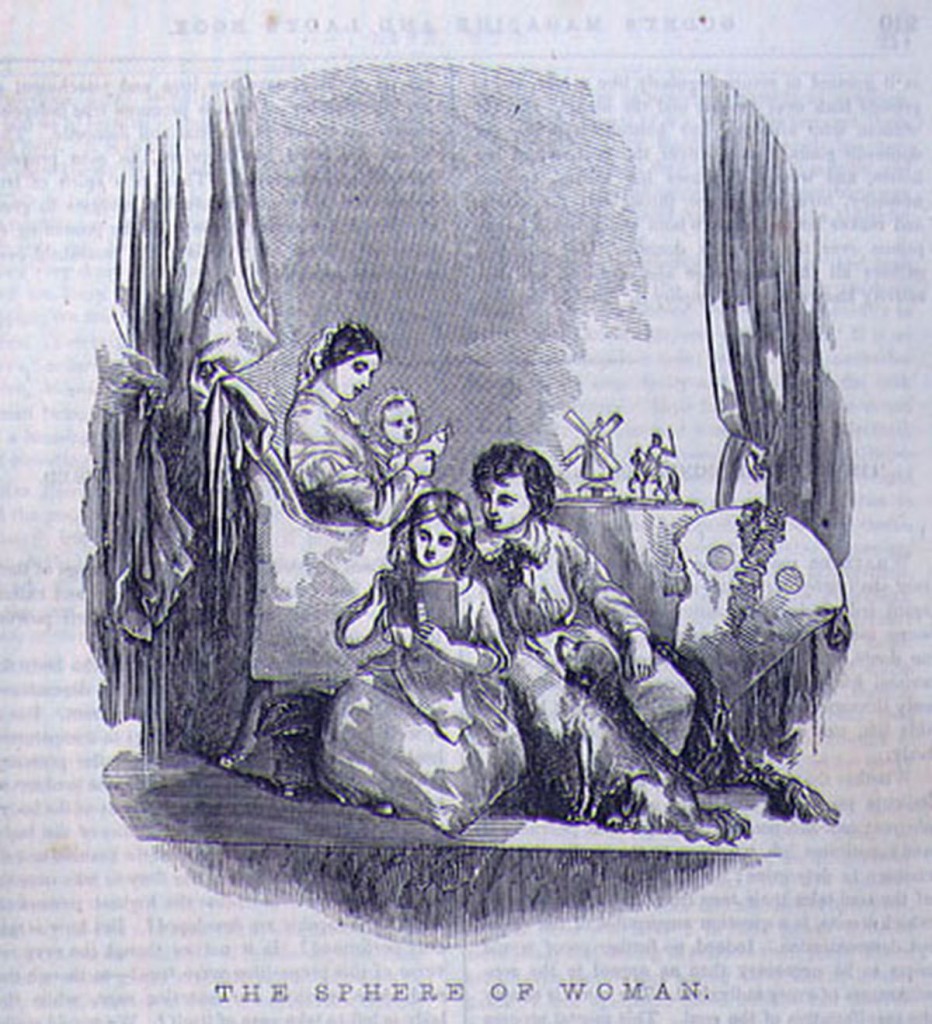

“The Sphere of Woman,” Godey’s Lady’s Book vol. 40 (March 1850): p. 209, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/sentimnt/gallgodyf.html.

Education equipped young women with the tools to live sophisticated, gentile lives. After sixteen-year-old Elizabeth Davis left home in 1816 to attend school, her father explained that the experience would “lay a foundation for your future character & respectability.” ((William Davis to Elizabeth Davis, 21 Mar 1816, 23 Jun 1816, 17 No 1816, Davis Family Papers, MHS)) After touring the United States in the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville praised the independence granted to the young American woman, who had “the great scene of the world…open to her” and whose education prepare her to exercise both reason and moral sense. ((Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Chapter IX.)) Middling young women also utilized their education to take positions as school teachers in the expanding common school system. Bristol Academy in Tauten, Maine, for instance, advertised “instruction…in the art of teaching” for female pupils. ((A Catalogue of the Officers, Teachers, and Pupils in Bristol Academy (Tauton, Mass.: Bradford & Amsbury, 1837).)) In 1825, Nancy Denison left Concord Academy with references indicating that she was “qualified to teach with success and profit” and “very cheerfully recommend[ed]” for “that very responsible employment.” ((Nancy Denison recommendation, May 1825; Titus Orcott Brown Papers, Maine Historical Society.))

As middle-class youths found opportunities for respectable employment through formal education, poor youths remained in marginalized positions. Their families’ desperate financial state kept them from enjoying the fruits of education. When pauper children did receive teaching through institutions such the House of Refuge in New York City, they were often simultaneously indentured to successful families to serve as field hands or domestic laborers. The Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents in New York City sent its wards to places like Sylvester Lusk’s farm in Enfield, Connecticut. Lusk took boys to learn “the trade and mystery of farming” and girls to learn “the trade and mystery of housewifery.” In exchange for “sufficient Meat, Drink, Apparel, Lodging, and Washing, fitting for an Apprentice,” and a rudimentary education, the apprentices promised obedience, morality, and loyalty. ((Indentures and Other Documents Binding Minor Wards of the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents of the City of New York as apprentices to Sylvester Lusk of Enfield, 1828-1838, Sylvester Lusk Papers, Connecticut Historical Society.)) Poor children also found work in factories such as Samuel Slater’s textile mills in southern New England. Slater published a newspaper advertisement for “four or five active Lads, about 15 Years of Age to serve as Apprentices in the Cotton Factory.” ((Advertisement in Providence Gazette, 1794.))

And so, during the early-nineteenth century, opportunities for education and employment often depended on a given family’s class. In colonial America, nearly all children worked within their parent’s chosen profession, whether it be agricultural or artisanal. During the market revolution, however, more children were able to postpone employment. Americans aspired to provide a “Romantic Childhood” – a period in which boys and girls were sheltered within the home and nurtured through primary schooling. ((Steven Mintz, Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004).)) This ideal was available to families that could survive without their children’s labor. And as such sheltered boys and girls matured, their early experiences often determined whether they entered respectable, well-paying positions or remained as dependent workers with little prospects for social mobility.

Just as children were expected to be sheltered from the adult world of work, American culture expected men and women to assume distinct gender roles as they prepared for marriage and family life. An ideology of “separate spheres” set the public realm—the world of economic production and political life—apart as a male domain, and the world of consumers and domestic life as a female one. (Even non-working women labored by shopping for the household, producing food and clothing, cleaning, educating children, and performing similar activities. But these were considered “domestic” because they did not bring money into the household, although they too were essential to the household’s economic viability.) While reality muddied the ideal, the divide between a private, female world of home and a public, male world of business defined American gender hierarchy.

The idea of separate spheres also displayed a distinct class bias. Middle- and upper-classes reinforced their status by shielding “their” women from the harsh realities of wage labor. Women were to be mothers and educators, not partners in production. But lower-class women continued to contribute directly to the household economy. The middle- and upper-class ideal was only feasible in households where women did not need to engage in paid labor. In poorer households, women engaged in wage labor as factory workers, piece-workers producing items for market consumption, tavern and inn keepers, and domestic servants. While many of the fundamental tasks women performed remained the same—producing clothing, cultivating vegetables, overseeing dairy production, and performing any number of other domestic labors—the key difference was whether and when they performed these tasks for cash in a market economy.

Domestic expectations constantly changed and the market revolution transformed many women’s traditional domestic tasks. Cloth production, for instance, advanced throughout the market revolution as new mechanized production increased the volume and variety of fabrics available to ordinary people. This relieved many better-off women of a traditional labor obligation. As cloth production became commercialized, women’s home-based cloth production became less important to household economies. Purchasing cloth, and later, ready-made clothes, began to transform women from producers to consumers. One woman from Maine, Martha Ballard, regularly referenced spinning, weaving, and knitting in the diary she kept from 1785 to 1812. ((Laurel Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 (New York: Knopf, 1990).)) Martha, her daughters, and female neighbors spun and plied linen and woolen yarns and used them to produce a variety of fabrics to make clothing for her family. The production of cloth and clothing was a year-round, labor-intensive process, but it was for home consumption, not commercial markets.

In cities, where women could buy cheap imported cloth to turn into clothing, they became skilled consumers. They stewarded their husbands’ money by comparing values and haggling over prices. In one typical experience, Mrs. Peter Simon, a captain’s wife, inspected twenty-six yards of Holland cloth to ensure it was worth the £130 price. ((Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor, Ties That Buy: Women and Commerce in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 138.)) Even wealthy women shopped for high-value goods. While servants or slaves routinely made low-value purchases, the mistress of the household trusted her discriminating eye alone for expensive or specific purchases.

Women might also parlay their feminine skills into businesses. In addition to working as seamstresses, milliners, or laundresses, women might undertake paid work for neighbors or acquaintances or combine clothing production with management of a boarding house. Even slaves with particular skill at producing clothing could be hired out for a higher price, or might even negotiate to work part-time for themselves. Most slaves, however, continued to produce domestic items, including simpler cloths and clothing, for home consumption.

Similar domestic expectations played out in the slave states. Enslaved women labored in the fields. Whites argued that African American women were less delicate and womanly than white women and therefore perfectly suited for agricultural labor. The southern ideal meanwhile established that white plantation mistresses were shielded from manual labor because of their very whiteness. Throughout the slave states, however, aside from the minority of plantations with dozens of slates, the majority of white women by necessity continued to assist with planting, harvesting, and processing agricultural projects despite the cultural stigma attached to it. White southerners continued to produce large portions of their food and clothing at home. Even when they were market-oriented producers of cash crops, white southerners still insisted that their adherence to plantation slavery and racial hierarchy made them morally superior to greedy Northerners and their callous, cutthroat commerce. Southerners and northerners increasingly saw their ways of life as incompatible.

While the market revolution remade many women’s economic roles, their legal status remained essentially unchanged. Upon marriage, women were rendered legally dead by the notion of coverture, the custom that counted married couples as a single unit represented by the husband. Without special precautions or interventions, women could not earn their own money, own their own property, sue, or be sued. Any money earned or spent belonged by law to their husbands. Women shopped on their husbands’ credit and at any time husbands could terminate their wives’ access to their credit. Although a handful of states made divorce available—divorce had before only been legal in Congregationalist states such as Massachusetts and Connecticut, where marriage was strictly a civil contract, rather than a religious one—it remained extremely expensive, difficult, and rare. Marriage was typically a permanently binding legal contract.

Ideas of marriage, if not the legal realities, began to change. This period marked the beginning of the shift from “institutional” to “companionate” marriage. ((Anya Jabour, Marriage in the Early Republic: Elizabeth and William Wirt and the Companionate Ideal (Baltimore, Md: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).)) Institutional marriages were primarily labor arrangements that maximized the couple’s and their children’s chances of surviving and thriving. Men and women assessed each other’s skills as they related to household production, although looks and personality certainly entered into the equation. But in the late-eighteenth century, under the influence by Enlightenment thought, young people began to privilege character and compatibility in their potential partners. Money was still essential: marriages prompted the largest redistributions of property prior to the settling of estates at death. But the means of this redistribution was changing. Especially in the North, land became a less important foundation for matchmaking as wealthy young men became not only farmers and merchants but bankers, clerks, or professionals. The increased emphasis on affection and attraction that young people embraced was facilitated by an increasingly complex economy that offered new ways to store, move, and create wealth, which liberalized the criteria by which families evaluated potential in-laws.

To be considered a success in family life, a middle-class American man typically aspired to own a comfortable home and to marry a woman of strong morals and religious conviction who would take responsibility for raising virtuous, well-behaved children. The duties of the middle-class husband and wife would be clearly delineated into separate spheres. The husband alone was responsible for creating wealth and engaging in the commerce and politics—the public sphere. The wife was responsible for the private—keeping a good home, being careful with household expenses, raising children, and inculcating them with the middle class virtues that would ensure their future success. But for poor families sacrificing the potential economic contributions of wives and children was an impossibility.

VI. The Rise of Industrial Labor in Antebellum America

More than five million immigrants arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1860. Irish, German, and Jewish immigrants sought new lives and economic opportunities. By the Civil War, nearly one out of every eight Americans had been born outside of the United States. A series of push and pull factors drew immigrants to the United States.

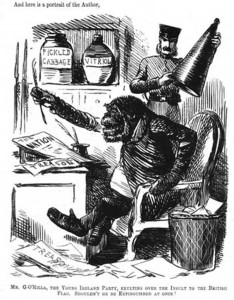

In England, an economic slump prompted Parliament to modernize British agriculture by revoking common land rights for Irish farmers. These policies generally targeted Catholics in the southern counties of Ireland and motivated many to seek greater opportunity and the booming American economy pulled Irish immigrants towards ports along the eastern United States. Between 1820 and 1840, over 250,000 Irish immigrants arrived in the United States. ((Bill Ong Hing, Defining America through Immigration Policy (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), p. 278-284.)) Without the capital and skills required to purchase and operate farms, Irish immigrants settled primarily in northeastern cities and towns and performed unskilled work. Irish men usually emigrated alone and, when possible, practiced what became known as chain migration. Chain migration allowed Irish men to send portions of their wages home, which would then be used to either support their families in Ireland or to purchase tickets for relatives to come to the United States. Irish immigration followed this pattern into the 1840s and 1850s, when the infamous Irish Famine sparked a massive exodus out of Ireland. Between 1840 and 1860, 1.7 million Irish fled starvation and the oppressive English policies that accompanied it. ((John Powell, Encyclopedia of North American Immigration (New York: Facts on File, 005), 154.)) As they entered manual, unskilled labor positions in urban America’s dirtiest and most dangerous occupations, Irish workers in northern cities were compared to African Americans and nativist newspapers portrayed them with ape-like features. Despite hostility, Irish immigrants retained their social, cultural, and religious beliefs and left an indelible mark on American culture.

.

John Tenniel, “Mr. G’Orilla,” c. 1845-52, via Wikimedia.

While the Irish settled mostly in coastal cities, most German immigrants used American ports and cities as temporary waypoints before settling in the rural countryside. Over 1.5 million immigrants from the various German states arrived in the United States during the antebellum era. Although some southern Germans fled declining agricultural conditions and repercussions of the failed revolutions of 1848, many Germans simply sought steadier economic opportunity. German immigrants tended to travel as families and carried with them skills and capital that enabled them to enter middle class trades. Germans migrated to the Old Northwest to farm in rural areas and practiced trades in growing communities such as St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Milwaukee, three cities that formed what came to be called the German Triangle.

Most German immigrants were Catholics, but many were Jewish. Although records are sparse, New York’s Jewish population rose from approximately 500 in 1825 to 40,000 in 1860. ((H.B. Grinstein, The Rise of the Jewish Community in New York, 1654-1860 (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1945), 469.)) Similar gains were seen in other American cities. Jewish immigrants, hailing from southwestern Germany and parts of occupied Poland, moved to the United States through chain migration and as family units. Unlike other Germans, Jewish immigrants rarely settled in rural areas. Once established, Jewish immigrants found work in retail, commerce, and artisanal occupations such as tailoring. They quickly found their footing and established themselves as an intrinsic part of the American market economy. Just as Irish immigrants shaped the urban landscape through the construction of churches and Catholic schools, Jewish immigrants erected synagogues and made their mark on American culture.

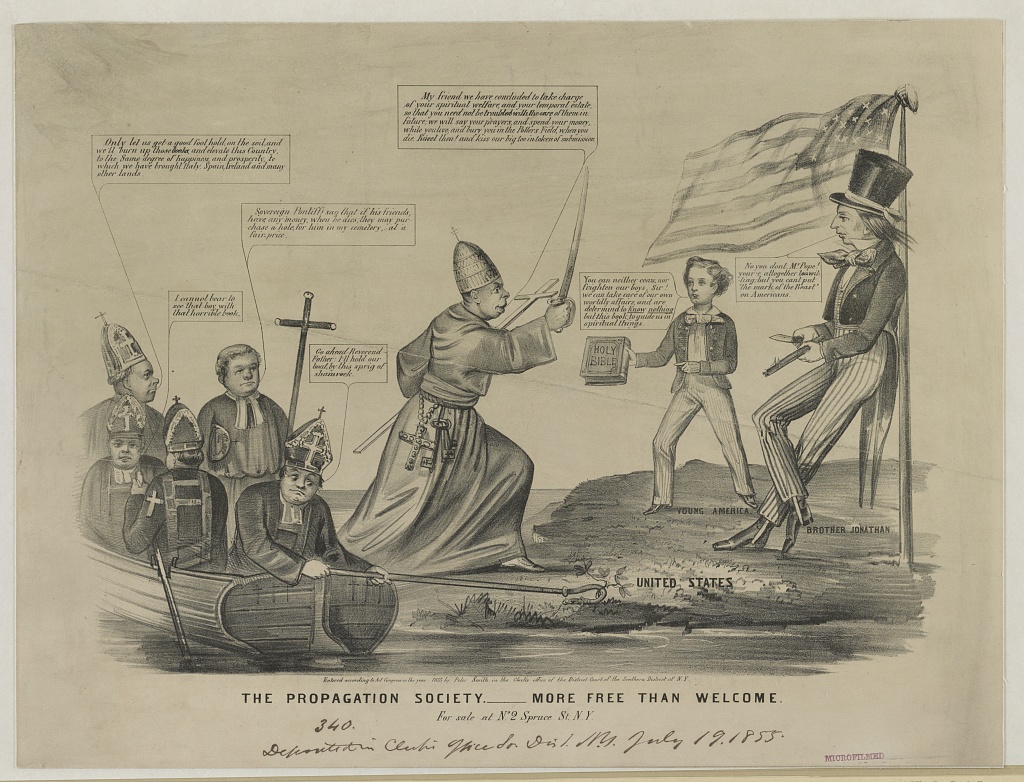

The sudden influx of immigration triggered a backlash among many native-born Anglo-Protestant Americans. This nativist movement, especially fearful of the growing Catholic presence, sought to limit European immigration and prevent Catholics from establishing churches and other institutions. Popular in northern cities such as Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other cities with large Catholic populations, nativism even spawned its own political party in the 1850s. The American Party, more commonly known as the “Know-Nothing Party,” found success in local and state elections throughout the North. The party even nominated candidates for President in 1852 and 1856. The rapid rise of the Know-Nothings, reflecting widespread anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment, slowed European immigration. Immigration declined precipitously after 1855 as nativism, the Crimean War, and improving economic conditions in Europe discouraged potential migrants from traveling to the United States. Only after the American Civil War would immigration levels match, and eventually surpass, the levels seen in the 1840s and 1850s.

In industrial northern cities, Irish immigrants swelled the ranks of the working class and quickly encountered the politics of industrial labor. Many workers formed trade unions during the early republic. Organizations such as the Philadelphia’s Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers or the Carpenters’ Union of Boston operated in within specific industries in major American cities and worked to protect the economic power of their members by creating closed shops—workplaces wherein employers could only hire union members—and striking to improve working conditions. Political leaders denounced these organizations as unlawful combinations and conspiracies to promote the narrow self-interest of workers above the rights of property holders and the interests of the common good. Unions did not become legally acceptable—and then only haltingly—until 1842 when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of a union organized among Boston bootmakers, arguing that the workers were capable of acting “in such a manner as best to subserve their own interests.” ((Commonwealth v. Hunt, 45 Mass. 111 (1842).))

N. Currier, “The Propagation Society, More Free than Welcome,” 1855, via Library of Congress.

In the 1840s, labor activists organized to limit working hours and protect children in factories. The New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workingmen (NEA) mobilized to establish a ten-hour day across industries. They argued that the ten-hour day would improve the immediate conditions of laborers by allowing “time and opportunities for intellectual and moral improvement.” ((The Artisan, 8 Mar 1832.)) After a city-wide strike in Boston in 1835, the Ten-Hour Movement quickly spread to other major cities such as Philadelphia. The campaign for leisure time was part of the male working-class effort to expose the hollowness of the paternalistic claims of employers and their rhetoric of moral superiority. ((Teresa Anne Murphy, Ten Hours’ Labor: Religion, Reform, and Gender in Early New England (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992).))

Women, a dominant labor source for factories since the early 1800s, launched some of the earliest strikes for better conditions. Textile operatives in Lowell, Massachusetts, “turned-out” (walked off) their jobs in 1834 and 1836. During the Ten-Hour Movement of the 1840s, female operatives provided crucial support. Under the leadership of Sarah Bagley, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association organized petition drives that drew thousands of signatures from “mill girls.” Like male activists, Bagley and her associates used the desire for mental improvement as a central argument for reform. An 1847 editorial in the Voice of Industry, a labor newspaper published by Bagley, asked “who, after thirteen hours of steady application to monotonous work, can sit down and apply her mind to deep and long continued thought?” (([Sarah Bagley], “The Blindness of the Age,” Voice of Industry, 23 Apr 1847.)) Despite the widespread support for a ten-hour day, the movement achieved only partial success. President Van Buren established a ten-hour-day policy for laborers on federal public works projects. New Hampshire passed a state-wide law in 1847 and Pennsylvania following a year later. Both states, however, allowed workers to voluntarily consent to work more than ten hours per day.

In 1842, child labor became a dominant issue in the American labor movement. The protection of child laborers gained more middle-class support, especially in New England, than the protection of adult workers. A petition from parents in Fall River, a southern Massachusetts mill town that employed a high portion of child workers, asked the legislature for a law “prohibiting the employment of children in manufacturing establishments at an age and for a number of hours which must be permanently injurious to their health and inconsistent with the education which is essential to their welfare.” ((Legislative Documents, 1842, House, No. 4, p. 3, in Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis Otey, The Beginnings of Child Labor Legislation in Certain States: a Comparative Study (New York: Arno Press, 1974), 78.)) Massachusetts quickly passed a law prohibiting children under the age of twelve from working more than ten hours a day. By the mid-nineteenth century, every state in New England had followed Massachusetts’ lead. Between the 1840s and 1860s, these statutes slowly extended the age of protection of labor and the assurance of schooling. Throughout the region, public officials agreed that young children (between nine and twelve years) should be prevented from working in dangerous occupations, and older children (between twelve and fifteen years) should balance their labor with education and time for leisure. ((Miriam E. Loughran, “The Historical Development of Child-Labor Legislation in the United States” (PhD diss., Catholic University of America, 1921), 67.))

Male workers, sought to improve their income and working conditions to create a household that kept women and children protected within the domestic sphere. But labor gains were limited and movement itself remained moderate. Despite its challenge to industrial working conditions, labor activism in antebellum America remained largely wedded to the free labor ideal. The labor movement supported the northern free soil movement, which challenged the spread of slavery, that emerged during the 1840s, simultaneously promoting the superiority of the northern system of commerce over the southern institution of slavery while trying, much less successfully, to reform capitalism.

VII. Conclusion

During the early nineteenth century, southern agriculture produced by slaves fueled northern industry produced by wage workers and managed by the new middle class. New transportation, new machinery, and new organizations of labor integrated the previously isolated pockets of the colonial economy into a national industrial operation. Industrialization and the cash economy tied diverse regions together at the same time ideology was driving Americans apart. By celebrating the freedom of contract that distinguished the wage worker from the indentured servant of previous generations or the slave in the southern cotton field, political leaders claimed the American Revolution’s legacy for the North. But the rise of industrial child labor, the demands of workers to unionize, the economic vulnerability of women, and the influx of non-Anglo immigrants left many Americans questioning the meaning of liberty after the market revolution.

Contributors

This chapter was edited by Jane Fiegen Green, with content contributions by Kelly Arehart, Myles Beaurpre, Kristin Condotta, Jane Fiegen Green, Nathan Jeremie-Brink, Lindsay Keiter, Brenden Kennedy, William Kerrigan, Chris Sawulla, David Schley, and Evgenia Shayder Shoop.

Recommended Reading

- Balleisen, Edward J. Navigating Failure: Bankruptcy and Commercial Society in Antebellum America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Blewett, Mary H. Men, Women, and Work: Class, Gender, and Protest in the New England Shoe Industry, 1780-1910. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

- Blumin, Stuart M. The Emergence of the Middle Class: Social Experience in the American City, 1760-1900. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Boydston, Jeanne. Home and Work: Housework, Wages, and the Ideology of Labor in the Early Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Dublin, Thomas. Transforming Women’s Work: New England Lives in the Industrial Revolution. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Faler, Paul G. Mechanics and Manufacturers in the Early Industrial Revolution: Lynn, Massachusetts, 1760-1860. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1981.

- Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Glickstein, Jonathan A. Concepts of Free Labor in Antebellum America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991.

- Greenberg, Joshua R. Advocating the Man: Masculinity, Organized Labor, and the Household in New York, 1800-1840. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Karen Halttunen. Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870. Yale University Press, 1982.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Innes, Stephen, ed. Work and Labor in Early America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

- Larson, John Lauritz. The Market Revolution in America: Liberty, Ambition, and the Eclipse of the Common Good. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Levy, Jonathan. Freaks of Fortune: The Emerging World of Capitalism and Risk in America. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Luskey, Brian P. On the Make: Clerks and the Quest for Capital in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: New York University Press, 2010.

- Melish, Joanne Pope. Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998.

- Stephen Mihm. A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States. Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Montgomery, David. Citizen Worker: The Experience of Workers in the United States with Democracy and the Free Market During the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Murphy, Teresa Anne. Ten Hours’ Labor: Religion, Reform, and Gender in Early New England. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

- Rice, Stephen P. Minding the Machine: Languages of Class in Early Industrial America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

- Rothenberg, Winifred Barr. From Market-Places to a Market Economy: The Transformation of Rural Massachusetts, 1750-1850. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Ryan, Mary P. Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County, New York, 1790-1865. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- Sellers, Charles Grier. The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Tucker, Barbara M. Samuel Slater and the Origins of the American Textile Industry, 1790-1860. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

- Zakim, Michael, and Gary John Kornblith, eds. Capitalism Takes Command: The Social Transformation of Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Zonderman, David A. Aspirations and Anxieties: New England Workers and the Mechanized Factory System, 1815-1850. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

![Buffalo Soldiers, the nickname given to African-American cavalrymen by the native Americans they fought, were the first peacetime all-black regiments in the regular United States army. These soldiers regularly confronted racial prejudice from other Army members and civilians, but were an essential part of American victories during the Indian Wars of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “[Buffalo soldiers of the 25th Infantry, some wearing buffalo robes, Ft. Keogh, Montana] / Chr. Barthelmess, photographer, Fort Keogh, Montana,” 1890. Library of Congress.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/11406v-1000x635.jpg)

![This photograph, taken only two years after the establishment of South Dakota, shows the dire situation of the Lakota people on what was formerly their own land. John C. Grabill, “[A young Oglala girl sitting in front of a tipi, with a puppy beside her, probably on or near Pine Ridge Reservation],” 1891. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99613799/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/02515v-500x658.jpg)

![American frontierswoman and professional scout Martha Jane Canary was better known to America as Calamity Jane. A figure in western folklore during her life and after, Calamity Jane was a central character in many of the increasingly popular novels and films that romanticized western life in the twentieth century. “[Martha Canary, 1852-1903, ("Calamity Jane"), full-length portrait, seated with rifle as General Crook's scout],” c. 1895. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005689345/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3a53082v-500x629.jpg)

![Conservative William McKinley promised prosperity to ordinary Americans through his “sound money” initiative, a policy he ran on during his election campaigns in 1896 and again in 1900. This election poster touts McKinley’s gold standard policy as bringing “Prosperity at Home, Prestige Abroad.” “Prosperity at home, prestige abroad,” [between 1895 and 1900]. Library of Congress,.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/18_McKinley_LC-USZC4-1329-1000x562.jpg)