From an undated William Jennings Bryan campaign print, “Shall the People Rule?” Library of Congress.

*The American Yawp is currently in beta draft. Please click here to help improve this chapter*

I. Introduction

“Never in the history of the world was society in so terrific flux as it is right now,” Jack London wrote in Iron Heel, his 1908 dystopian novel in which a corporate oligarchy comes to rule the United States. He wrote, “The swift changes in our industrial system are causing equally swift changes in our religious, political, and social structures. An unseen and fearful revolution is taking place in the fiber and structure of society. One can only dimly feel these things, but they are in the air, now, today.”

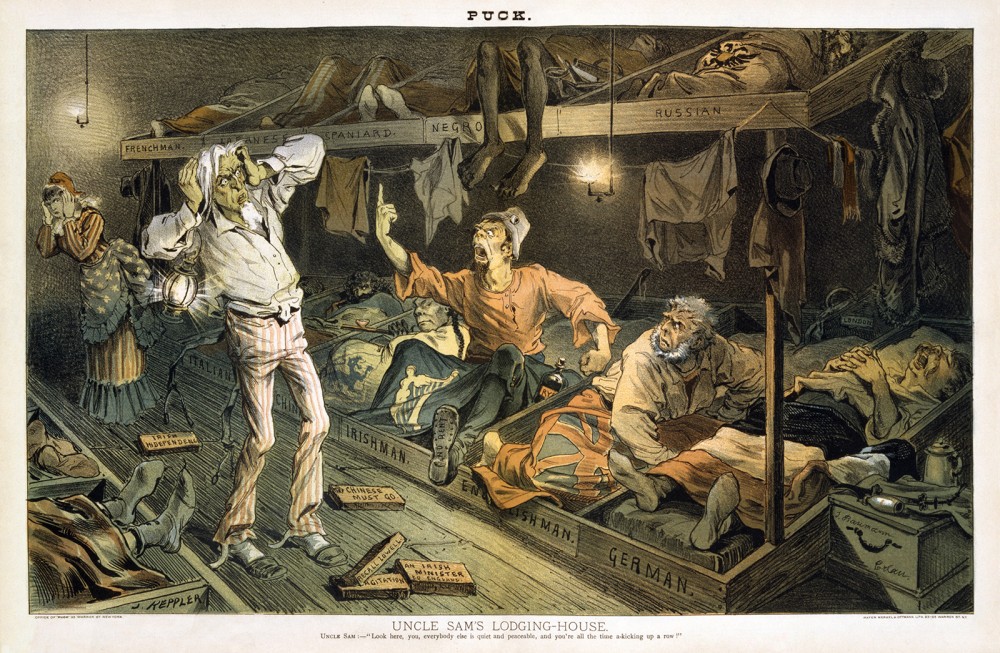

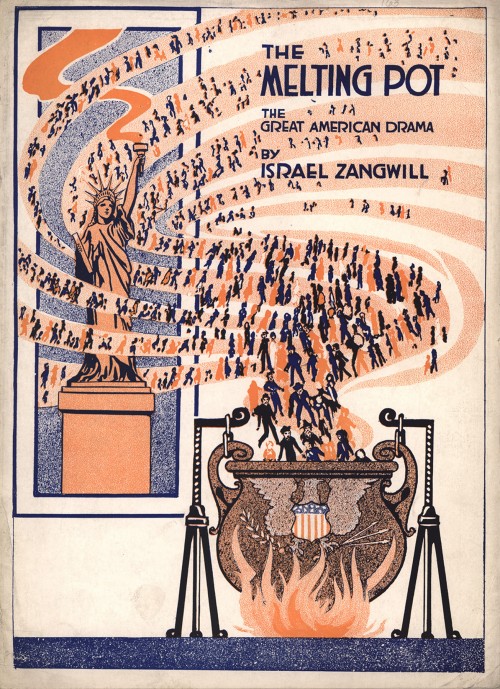

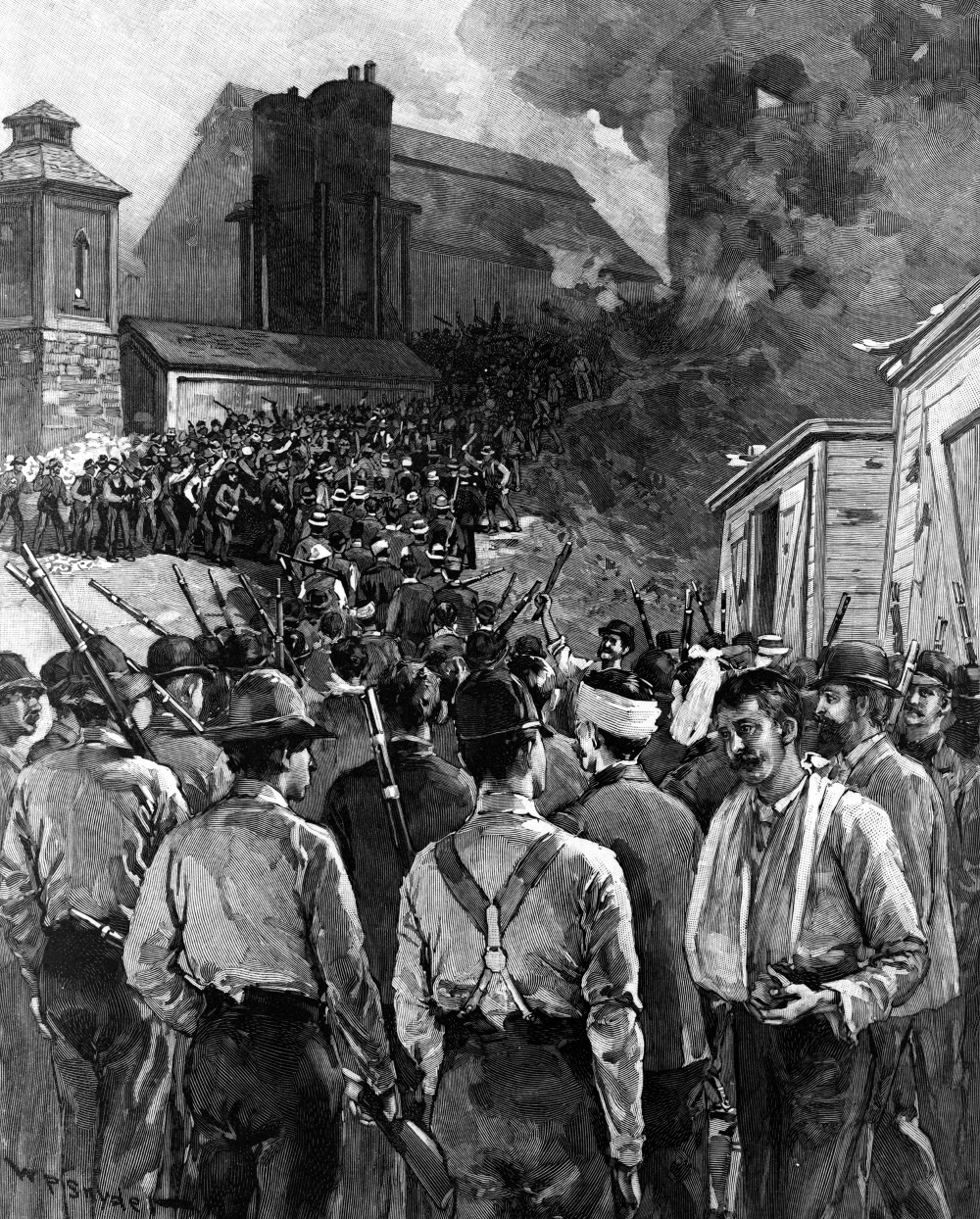

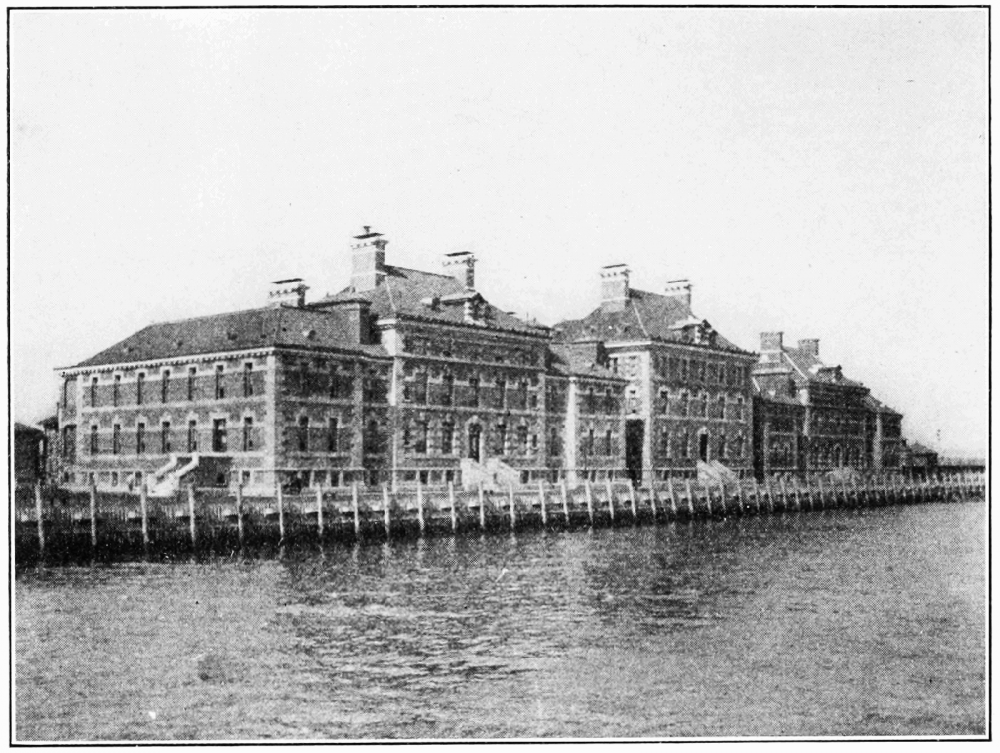

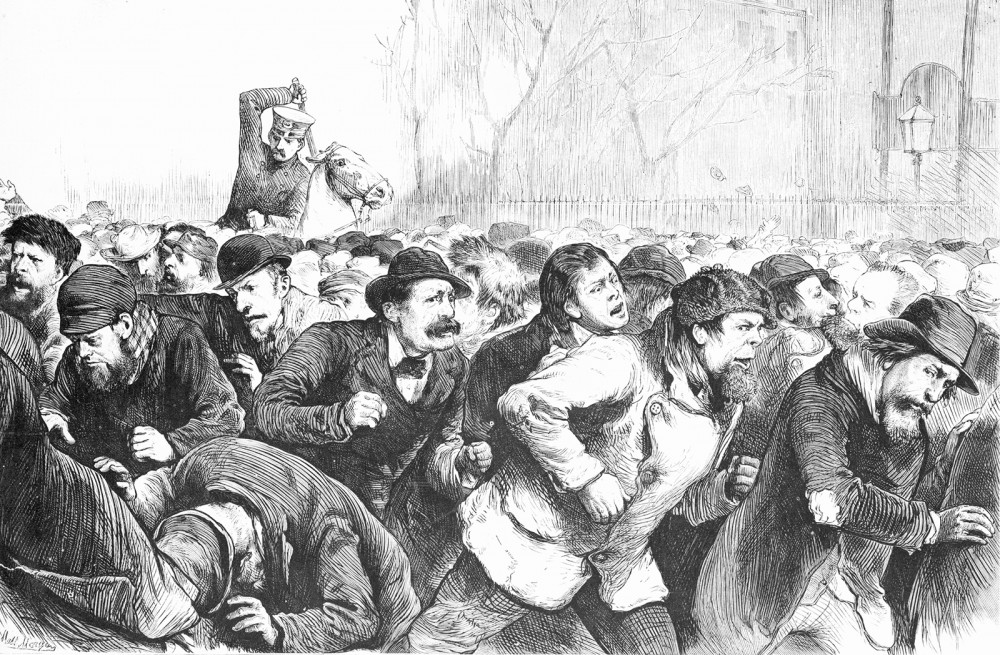

The many problems associated with the Gilded Age—the rise of unprecedented fortunes and unprecedented poverty, controversies over imperialism, urban squalor, a near-war between capital and labor, loosening social mores, unsanitary food production, the onrush of foreign immigration, environmental destruction, and the outbreak of political radicalism—confronted Americans. Terrible forces seemed out of control and the nation seemed imperiled. Farmers and workers had been waging political war against capitalists and political conservatives for decades, but then, slowly, toward the end of the nineteenth century a new generation of middle class Americans interjected themselves into public life and advocated new reforms to tame the runaway world of the Gilded Age.

Widespread dissatisfaction with new trends in American society spurred the Progressive Era, named for the various “progressive” movements that attracted various constituencies around various reforms. Americans had many different ideas about how the country’s development should be managed and whose interests required the greatest protection. Reformers sought to clean up politics, black Americans continued their long struggle for civil rights, women demanded the vote with greater intensity while also demanding a more equal role in society at large, and workers demanded higher wages, safer workplaces and the union recognition that would guarantee these rights. Whatever their goals, “reform” became the word of the age, and the sum of their efforts, whatever their ultimate impact or original intentions, gave the era its name.

II. Mobilizing for Reform

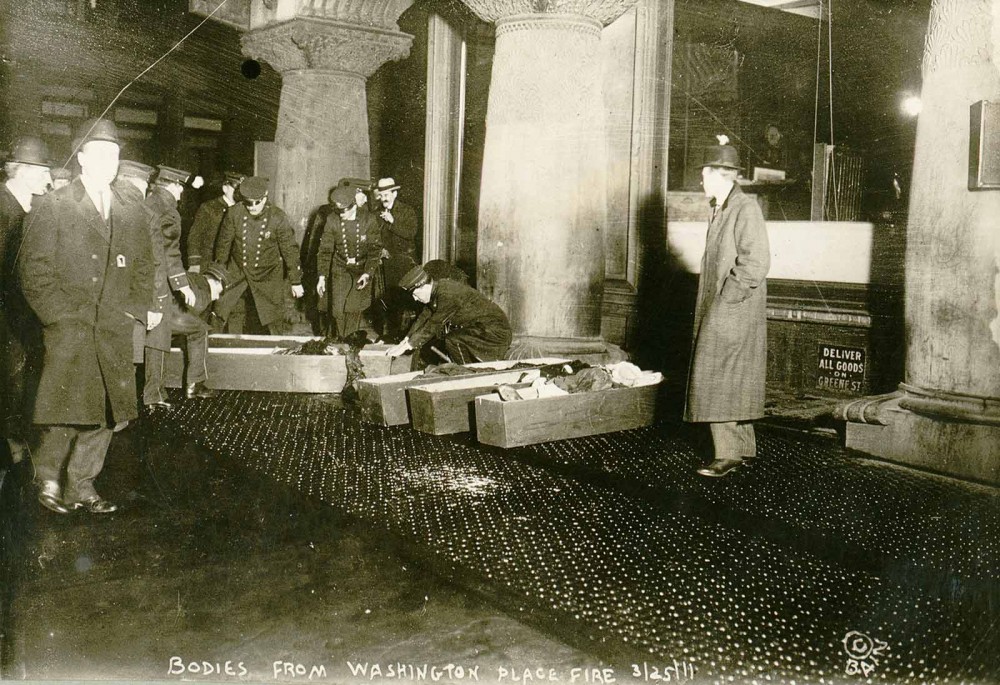

In 1911 the Triangle Shirtwaist factory in Manhattan caught fire. The doors of the factory had been chained shut to prevent employees from taking unauthorized breaks (the managers who held the keys saved themselves, but left over 200 women behind). A rickety fire ladder on the side of the building collapsed immediately. Women lined the rooftop and windows of the ten story building and jumped, landing in a “mangled, bloody pulp.” Life nets held by firemen tore at the impact of the falling bodies. Among the onlookers, “women were hysterical, scores fainted; men wept as, in paroxysms of frenzy, they hurled themselves against the police lines.” By the time the fire burned itself out 71 workers were injured and 146 had died.

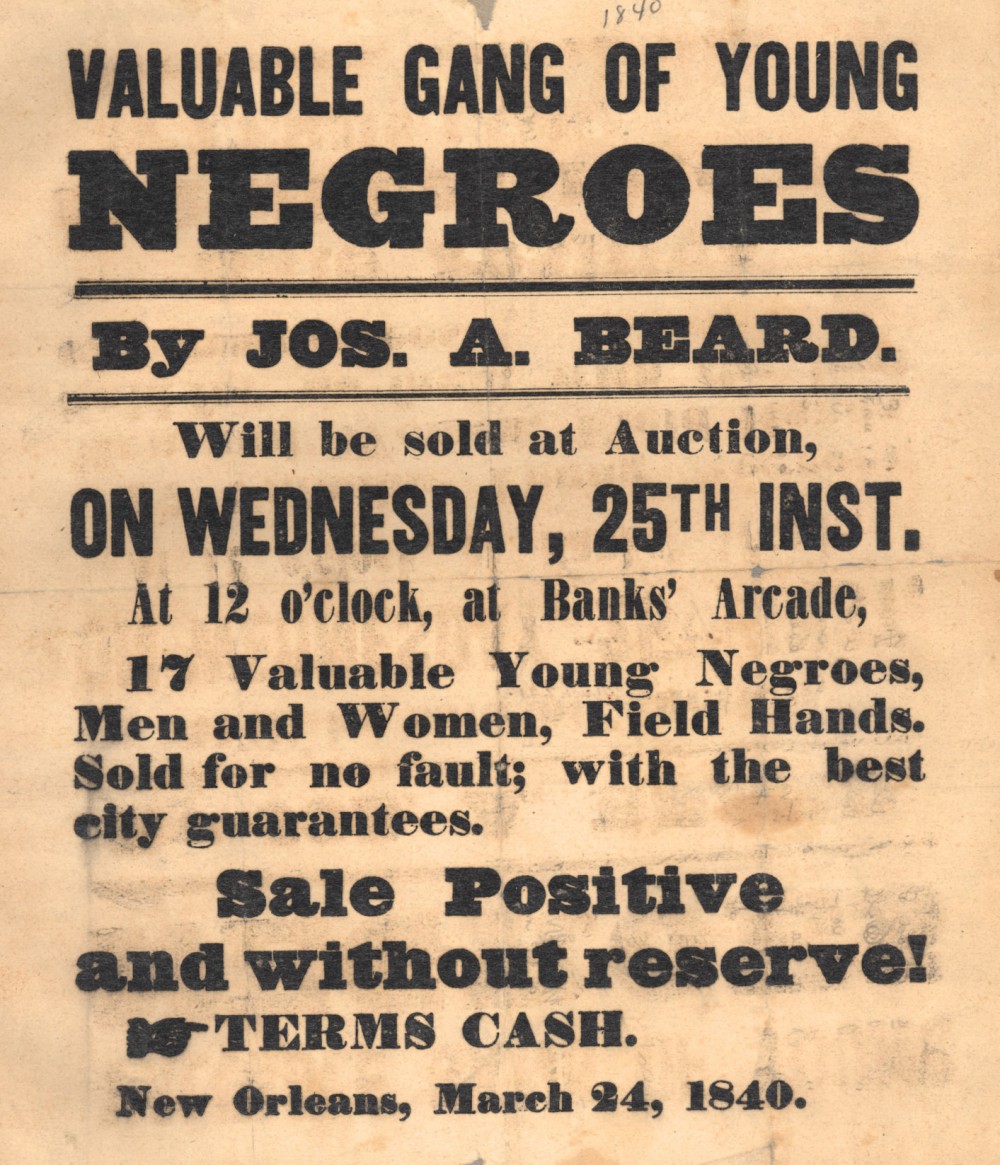

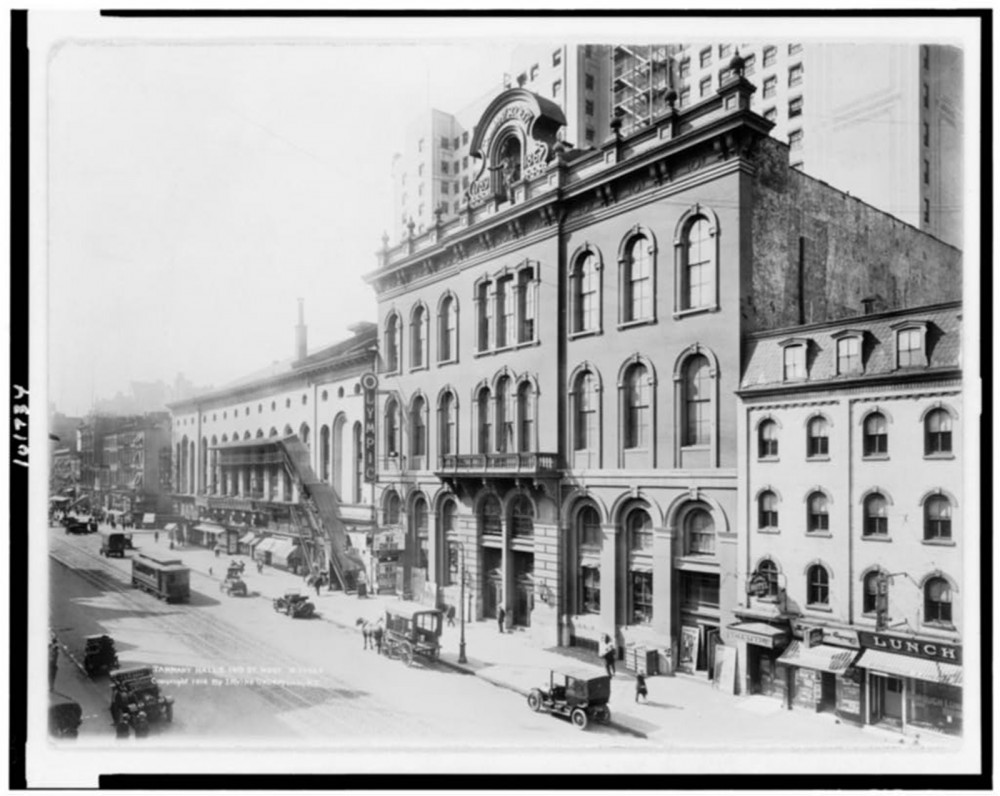

Photographs like this one made real the potential atrocities resulting from unsafe working conditions, as policemen place the bodies of workers burnt alive in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist fire into coffins. “Bodies from Washington Place fire, Mar 1911,” March 25, 1911. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98502780/.

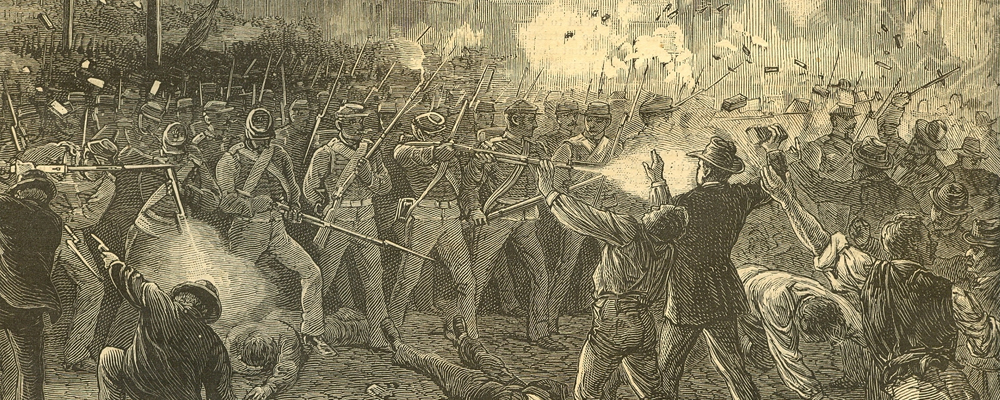

A year before, the Triangle workers had gone out on strike demanding union recognition, higher wages, and better safety conditions. Remembering their workers’ “chief value,” the owners of the factory decided that a viable fire escape and unlocked doors were too expensive and called in the city police to break up the strike. After the 1911 fire, reporter Bill Shepherd reflected, “I looked upon the heap of dead bodies and I remembered these girls were shirtwaist makers. I remembered their great strike last year in which the same girls had demanded more sanitary conditions and more safety precautions in the shops. These dead bodies were the answer.” Former Triangle worker and labor organizer Rose Schneiderman said, “This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in this city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers… the life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred! There are so many of us for one job, it matters little if 140-odd are burned to death.” After the fire Triangle owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris were brought up on manslaughter charges. They were acquitted after less than two hours of deliberation. The outcome continued a trend in the industrializing economy that saw workers’ deaths answered with little punishment of the business owners responsible for such dangerous conditions. But as such tragedies mounted and working and living conditions worsened and inequality grew, it became increasingly difficult to develop justifications for this new modern order.

Events such as the Triangle Shirtwaist fire convinced many Americans of the need for reform, but the energies of activists were needed to spread a new commitment to political activism and government interference in the economy. Politicians, journalists, novelists, religious leaders, and activists all raised their voices to push Americans toward reform.

Reformers turned to books and mass-circulation magazines to publicize the plight of the nation’s poor and the many corruptions endemic to the new industrial order. Journalists who exposed business practices, poverty, and corruption—labeled by Theodore Roosevelt as “Muckrakers”— aroused public demands for reform. Magazines such as McClure’s detailed political corruption and economic malfeasance. The Muckrakers confirmed Americans’ suspicions about runaway wealth and political corruption. Ray Stannard Baker, a journalist whose reports on United States Steel exposed the underbelly of the new corporate capitalism, wrote, “I think I can understand now why these exposure articles took such a hold upon the American people. It was because the country, for years, had been swept by the agitation of soap-box orators, prophets crying in the wilderness, and political campaigns based upon charges of corruption and privilege which everyone believed or suspected had some basis of truth, but which were largely unsubstantiated.”

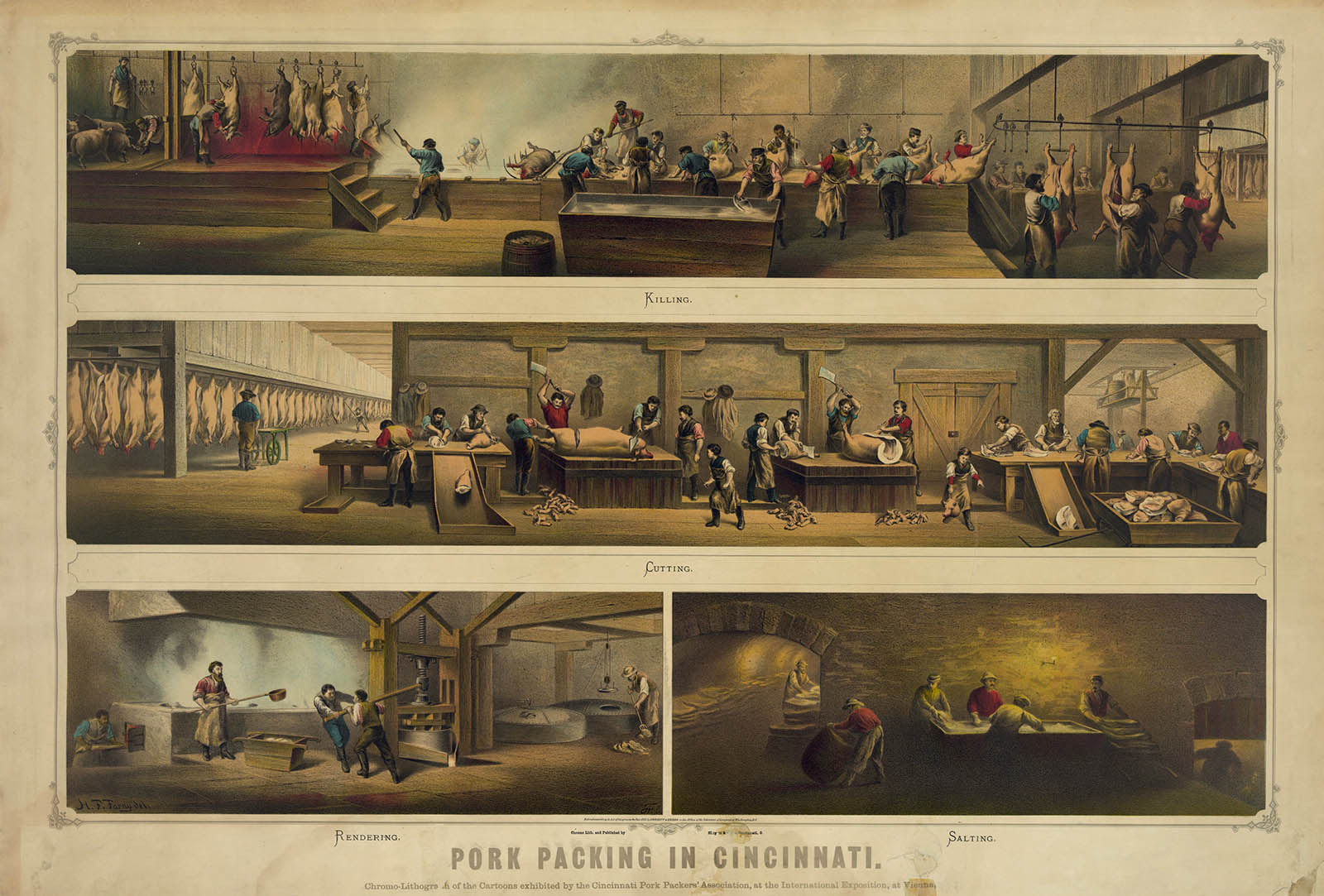

Journalists shaped popular perceptions of Gilded Age injustice. In 1890, New York City journalist Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives, a scathing indictment of living and working conditions in the city’s slums. Riis not only vividly described the squalor he saw, he documented it with photography, giving readers an unflinching view of urban poverty. Riis’s book led to housing reform in New York and other cities, and helped instill the idea that society bore at least some responsibility for alleviating poverty. In 1906, Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, a novel dramatizing the experiences of a Lithuanian immigrant family who moved to Chicago to work in the Stock Yards. Although Sinclair intended the novel to reveal the brutal exploitation of labor in the meatpacking industry, and thus to build support for the socialist movement, its major impact was to lay bare the entire process of industrialized food production. The growing invisibility of slaughterhouses and livestock production for urban consumers had enabled unsanitary and unsafe conditions. “The slaughtering machine ran on, visitors or no visitors,” wrote Sinclair, “like some horrible crime committed in a dungeon, all unseen and unheeded, buried out of sight and of memory.” Sinclair’s exposé led to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906.

“Home of an Italian Ragpicker.” Via Preus Museum

Of course, it was not only journalists who raised questions about American society. One of the most popular novels of the nineteenth century, Edward Bellamy’s 1888 Looking Backward, was a national sensation. In it, a man falls asleep in Boston in 1887 and awakens in 2000 to find society radically altered. Poverty and disease and competition gave way as new industrial armies cooperated to build a utopia of social harmony and economic prosperity. Bellamy’s vision of a reformed society enthralled readers, inspired hundreds of Bellamy clubs, and pushed many young readers onto the road to reform.

“I am aware that you called yourselves free in the nineteenth century. The meaning of the word could not then, however, have been at all what it is at present, or you certainly would not have applied it to a society of which nearly every member was in a position of galling personal dependence upon others as to the very means of life, the poor upon the rich, or employed upon employer, women upon men, children upon parents.” Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward

But Americans were urged to action not only by books and magazines but by preachers an theologians, too. Confronted by both the benefits and the ravages of industrialization, many Americans asked themselves, “What Would Jesus Do?” In 1896 Charles Sheldon, a Congregational minister in Topeka, Kansas, published In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do? The novel told the story of Henry Maxwell, a pastor in a small Midwestern town one day confronted by an unemployed migrant who criticized his congregation’s lack of concern for the poor and downtrodden. Moved by the man’s plight, Maxwell preached a series of sermons in which he asked his congregation: “Would it not be true, think you, that if every Christian in America did as Jesus would do, society itself, the business world, yes, the very political system under which our commercial and government activity is carried on, would be so changed that human suffering would be reduced to a minimum?” Sheldon’s novel became a best seller, not only because of its story but because the book’s plot connected with a new movement transforming American religion: the social gospel.

The social gospel emerged within Protestant Christianity at the end of the nineteenth century. It emphasized the need for Christians to be concerned for the salvation of society, and not simply individual souls. Instead of just caring for family or fellow church members, social gospel advocates encouraged Christians to engage society, challenge social, political, and economic structures, and help those less fortunate than themselves. Responding to the developments of the industrial revolution in America and the increasing concentration of people in urban spaces, with its attendant social and economic problems, some social gospelers went so far as to advocate a form of Christian socialism, but all urged Americans to confront the sins of their society.

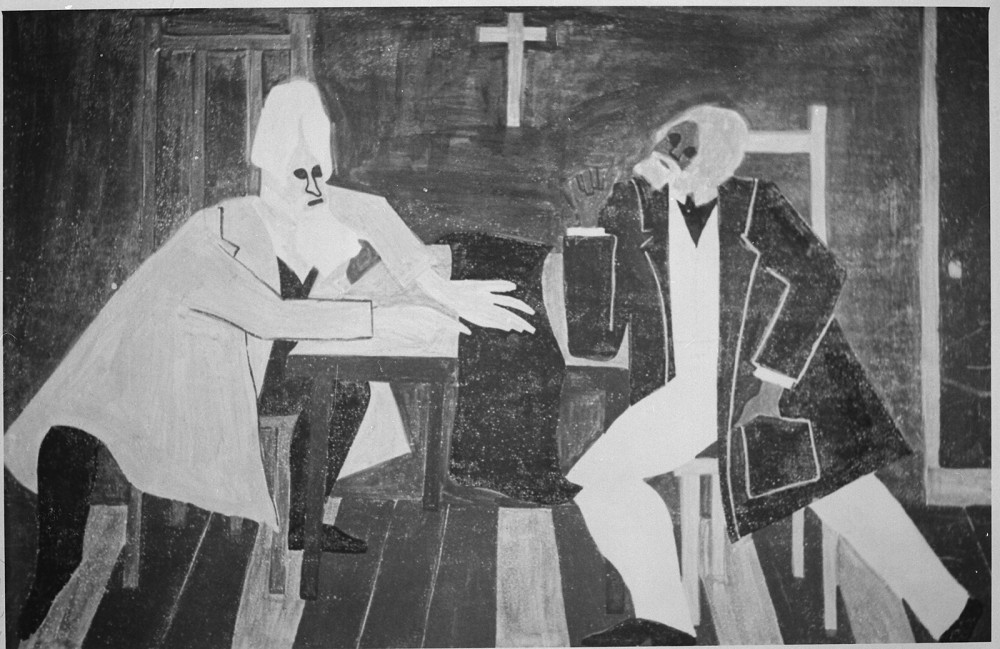

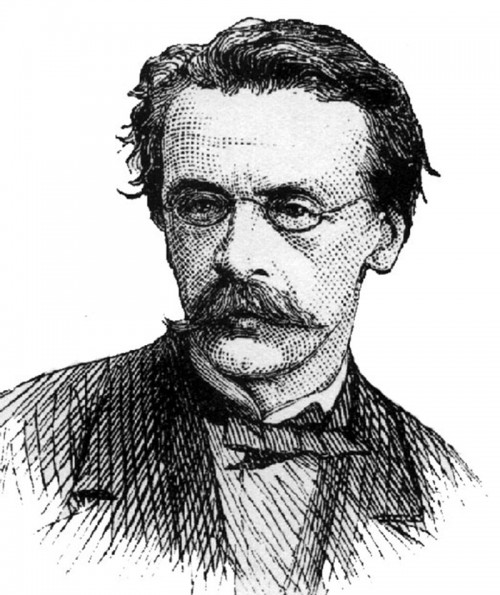

One of the most notable advocates of the social gospel was Walter Rauschenbusch. After graduating from Rochester Theological Seminary, in 1886 Rauschenbusch accepted the pastorate of a German Baptist church in the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York City, where he was confronted by rampant crime and stark poverty, problems not adequately addressed by the political leaders of the city. Rauschenbusch joined with fellow reformers to elect a new mayoral candidate, but he also realized that a new theological framework had to reflect his interest in society and its problems. He revived Jesus’ phrase, “the Kingdom of God,” claiming that it encompassed every aspect of life and made every part of society a purview of the proper Christian. Like Charles Sheldon’s Rev. Maxwell, Rauschenbusch believed that every Christian, whether they were a businessperson, a politician, or stay-at-home parent, should ask themselves what they could to enact the kingdom of God on Earth.

“The social gospel is the old message of salvation, but enlarged and intensified. The individualistic gospel has taught us to see the sinfulness of every human heart and has inspired us with faith in the willingness and power of God to save every soul that comes to him. But it has not given us an adequate understanding of the sinfulness of the social order and its share in the sins of all individuals within it. It has not evoked faith in the will and power of God to redeem the permanent institutions of human society from their inherited guilt of oppression and extortion. Both our sense of sin and our faith in salvation have fallen short of the realities under its teaching. The social gospel seeks to bring men under repentance for their collective sins and to create a more sensitive and more modern conscience. It calls on us for the faith of the old prophets who believed in the salvation of nations.” Walter Rauschenbush, A Theology For The Social Gospel, 1917

Glaring blindspots persisted within the proposals of most social gospel advocates. As men, they often ignored the plight of women and thus most refused to support women’s suffrage. Many were also silent on the plight of African Americans, Native Americans, and other oppressed minority groups. However, Rauschenbusch and other social gospel proponents’ writings would have a profound influence upon twentieth-century American life, not only most immediately in progressive reform but later, too, inspiring Martin Luther King, Jr., for instance, to envision a “beloved community” that resembled Rauschenbusch’s “Kingdom of God.”

III. Women’s Movements

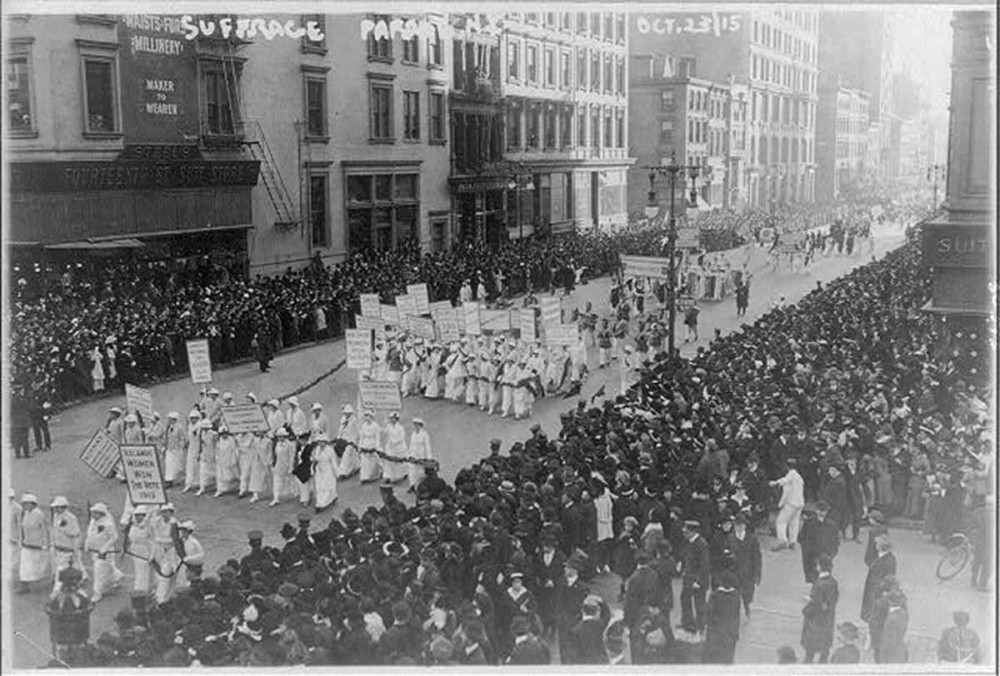

Suffragists campaigned tirelessly for the vote in the first two decades of the twentieth century, taking to the streets in public displays like this 1915 pre-election parade in New York City. During this one event, 20,000 women defied the gender norms that tried to relegate them to the private sphere and deny them the vote. Photograph, 1915. Wikimedia.

Reform opened new possibilities for women’s activism in American public life and gave new impetus to the long campaign for women’s suffrage. Much energy for women’s work came from female “clubs,” social organizations devoted to various purposes. Some focused on intellectual development, others emphasized philanthropic activities. Increasingly, these organizations looked outwards, to their communities, and to the place of women in the larger political sphere.

Women’s clubs flourished in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. In 1890s women formed national women’s club federations. Particularly significant in campaigns for suffrage and women’s rights were the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (formed in New York City in 1890) and the National Association of Colored Women (organized in Washington, D.C., in 1896), both of which were dominated by upper-middle-class, educated, northern women. Few of these organizations were bi-racial, a legacy of the sometimes uneasy mid-nineteenth-century relationship between socially active African Americans and white women. Rising American prejudice led many white female activists to ban inclusion of their African American sisters. The segregation of black women into distinct clubs nonetheless still produced vibrant organizations that could promise racial uplift and civil rights for all blacks, as well as equal rights for women.

Other women worked through churches and moral reform organizations to clean up American life. And still others worked as moral vigilantes. The fearsome Carrie A. Nation, an imposing woman who believed she worked God’s will, won headlines for destroying saloons. In Wichita, Kansas, on December 27, 1900, Nation took a hatchet and broke bottles and bars at the luxurious Carey Hotel. Arrested and charged with $3000 in damages, Nation spent a month in jail before the county dismissed the charges on account of “a delusion to such an extent as to be practically irresponsible.” But Nation’s “hatchetation” drew national attention. Describing herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like,” she continued her assaults, and days later smashed two more Wichita bars.

Few women followed in Nation’s footsteps, and many more worked within more reputable organizations. Nation, for instance, had founded a chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, (WCTU) but the organizations’ leaders described her as “unwomanly and unchristian.” The WCTU was founded in 1874 as a modest temperance organization devoted to combatting the evils of drunkenness. But then, from 1879 to 1898, Frances Willard invigorated the organization by transforming it into a national political organization, embracing a “do everything” policy that adopted any and all reasonable reforms that would improve social welfare and advance women’s rights. Temperance, and then the full prohibition of alcohol, however, always loomed large.

Many American reformers associated alcohol with nearly every social ill. Alcohol was blamed for domestic abuse, poverty, crime, and disease. The 1912 Anti-Saloon League Yearbook, for instance, presented charts indicating comparable increases in alcohol consumption alongside rising divorce rates. The WCTU called alcohol of being a “home wrecker.” More insidiously, perhaps, reformers also associated alcohol with cities and immigrants, necessarily maligning America’s immigrants, Catholics, and working classes in their crusade against liquor. Still, reformers believed that the abolition of “strong drink” would bring about social progress, would obviate the need for prisons and insane asylums, would save women and children from domestic abuse, and usher in a more just, progressive society.

From the club movement and temperance campaigns emerged powerful, active, female activists. Perhaps no American reformer matched Jane Addams’ in fame, energy, and innovation. Born in Cedarville, Illinois, in 1860, Addams lost her mother by the age of two and lived under the attentive care of her father. At seventeen, she left home to attend Rockford Female Seminary. An idealist, Addams sought the means to make the world a better place. She believed that well-educated women of means, such as herself, lacked practical strategies for engaging everyday reform. After four years at Rockford, Addams embarked upon on a multi-year “grand tour” of Europe. Jane found herself drawn to English settlement houses, a kind of prototype for social work in which philanthropists embedded themselves within communities and offered services to disadvantaged populations. After visiting London’s Toynbee Hall, the first settlement house, in 1887, Addams returned to the US and in 1889 founded Hull House in Chicago with her longtime confidant and companion Ellen Gates Starr.

The Settlement … is an experimental effort to aid in the solution of the social and industrial problems which are engendered by the modern conditions of life in a great city. It insists that these problems are not confined to any one portion of the city. It is an attempt to relieve, at the same time, the overaccumulation at one end of society and the destitution at the other … It must be grounded in a philosophy whose foundation is on the solidarity of the human race, a philosophy which will not waver when the race happens to be represented by a drunken woman or an idiot boy. Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House

Hull House workers provided for their neighbors by running a nursery and a kindergarten, administering classes for parents and clubs for children, and organizing social and cultural events for the community. Florence Kelley stayed at Hull House from 1891 to 1899, taking the settlement house model to New York and founding the Henry Street Settlement there. But Kelley also influenced Addams, convincing her to move into the realm of social reform. Hull House began exposing sweat shop conditions and advocating for worker organization. She called the conditions caused by urban poverty and industrialization a “social crime.” Hull House workers surveyed their community and produced statistics of poverty, disease, and living conditions that proved essential for reformers. Addams began pressuring politicians. Together Kelley and Addams petitioned legislators to pass anti-sweatshop legislation passed that limited the hours of work for women and children to eight per day. Yet Addams was an upper class white Protestant women who had faced limits, like many reformers, in embracing what seemed to them radical policies. While Addams called labor organizing a “social obligation,” she also warned the labor movement against the “constant temptation towards class warfare.” Addams, like many reformers, favored cooperation between rich and poor and bosses and workers, whether cooperation was a realistic possibility or not.

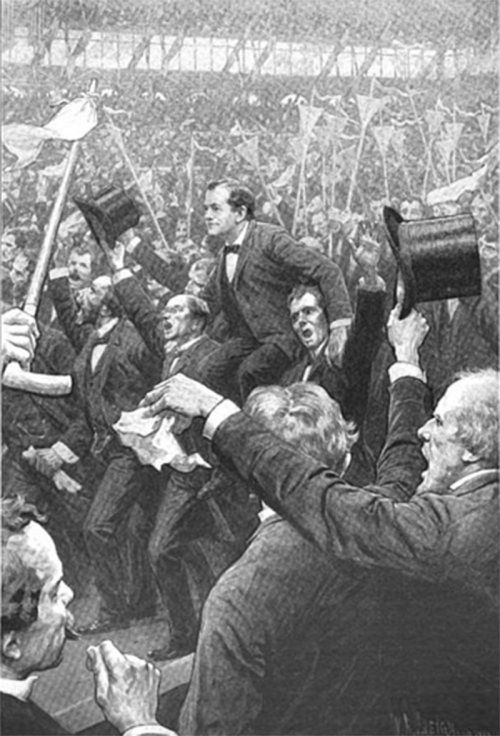

Addams became a kind of celebrity. In 1912, she became the first woman to give a nominating speech at a major party convention when she seconded the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt as the Progressive Party’s candidate for president. Her campaigns for social reform and women’s rights won headlines and her voice became ubiquitous in progressive politics.

Addams’ concerns grew beyond domestic concerns. Beginning with her work in the Anti-Imperialist League during the Spanish-American War Addams increasingly began to see militarism as a drain on resources better spent on social reform. In 1907 she wrote Newer Ideals of Peace, a book that would become for many a philosophical foundation of pacifism. Addams emerged as a prominent opponent of America’s entry into World War I. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

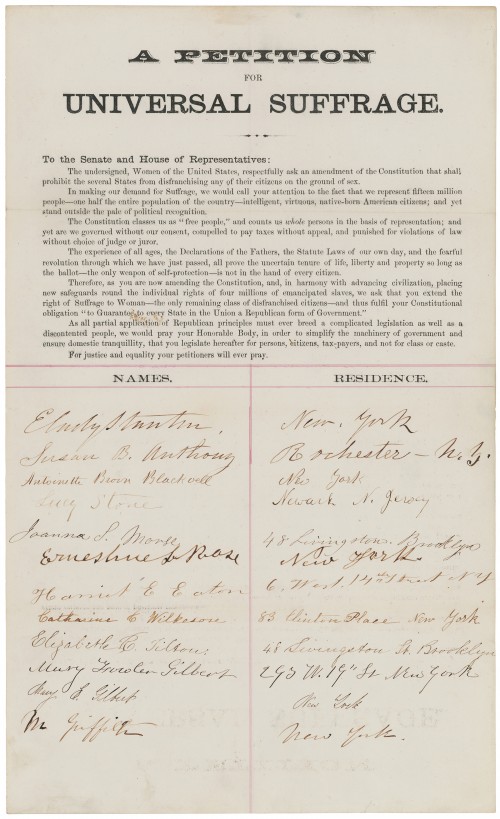

It would be suffrage, ultimately, that would mark the full emergence of women in American public life. Generations of women—and, occasionally, men—had pushed for women’s suffrage. Suffragists’ hard work resulted in slow but encouraging steps forward during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Notable victories were won in the West, where suffragists mobilized large numbers of women and male politicians were open to experimental forms of governance. By 1911, six western states had passed suffrage amendments to their constitutions.

Women’s suffrage was typically entwined with a wide range of reform efforts. Many suffragists argued that women’s votes were necessary to clean up politics and combat social evils. By the 1890s, for example, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, then the largest women’s organization in America, endorsed suffrage. Working-class women organized the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) in 1905 and campaigned for the vote alongside the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), a leading suffrage organization comprised largely of middle and upper-class women. WTUL members viewed the vote as a way to further their economic interests and to foster a new sense of respect for working-class women. “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist,” said Rose Schneiderman, a WTUL leader, during a 1912 speech. “The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.”

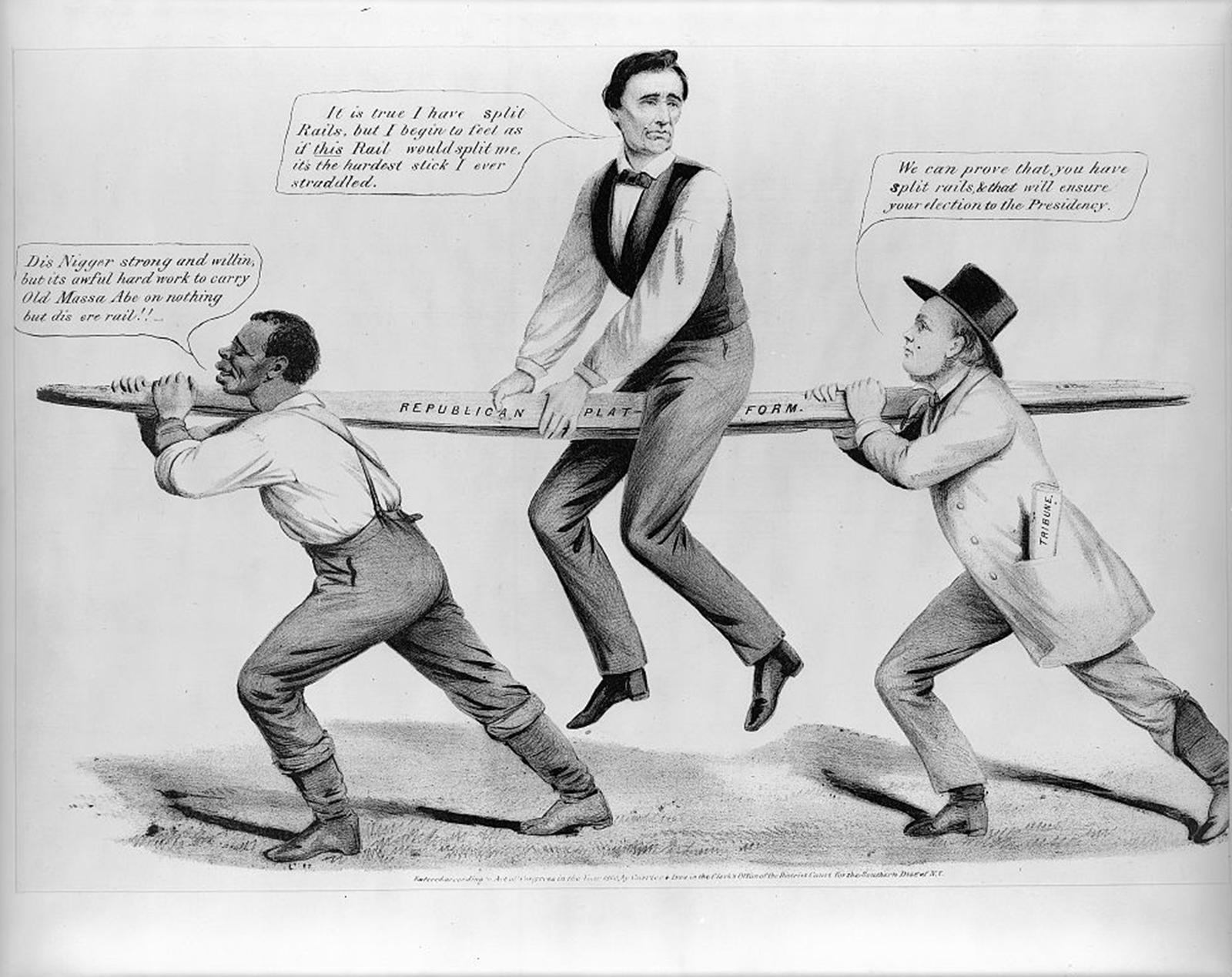

Many suffragists adopted a much crueler message. Some, even outside of the South, argued that white women’s votes were necessary to maintain white supremacy. Many American women found it advantageous to base their arguments for the vote on the necessity of maintaining white supremacy by enfranchising white, upper and middle class women. These arguments even stretched into international politics. But whatever the message, the suffrage campaign was winning.

The final push for women’s suffrage came on the eve of World War I. Determined to win the vote, NAWSA developed a dual strategy that focused on the passage of state voting rights laws and on the ratification of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Meanwhile, a new, more militant, suffrage organization emerged on the scene. Led by Alice Paul, the National Woman’s Party (NWP) took to the streets to demand voting rights, organizing marches and protests that mobilized thousands of women. Beginning in January 1917, NWP members also began to picket the White House, an action that led to the arrest and imprisonment of over 150 women.

In January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson declared his support for the women’s suffrage amendment and, two years later women’s suffrage became a reality. After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, women from all walks of life mobilized to vote. They were driven by both the promise of change, but also in some cases by their anxieties about the future. Much had changed since their campaign began, the US was now more industrial than not, increasingly more urban than rural. The activism and activities of these new urban denizens also gave rise to a new American culture.

IV. Targeting the Trusts

In one of the defining books of the Progressive Era, The Promise of American Life, Herbert Croly argued that because “the corrupt politician has usurped too much of the power which should be exercised by the people,” the “millionaire and the trust have appropriated too many of the economic opportunities formerly enjoyed by the people.” Croly and other reformers believed that wealth inequality eroded democracy and reformers had to win back for the people the power usurped by the moneyed trusts. But what exactly were these “trusts,” and why did it suddenly seem so important to reform them?

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a “trust” was a monopoly or cartel associated with the large corporations of the Gilded and Progressive Eras who entered into agreements—legal or otherwise—or consolidations to exercise exclusive control over a specific product or industry under the control of a single entity. Certain types of monopolies, specifically for intellectual property like copyrights, patents, trademarks and trade-secrets, are protected under the Constitution for the “to promote the progress of science and useful arts,” but for power entities to control entire national markets was something wholly new, and, for many Americans, wholly unsettling.

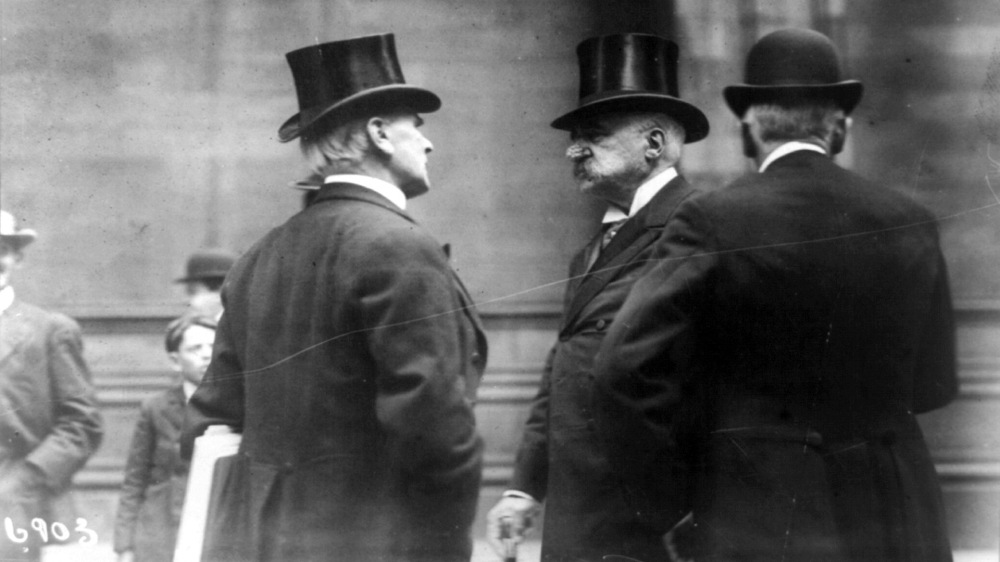

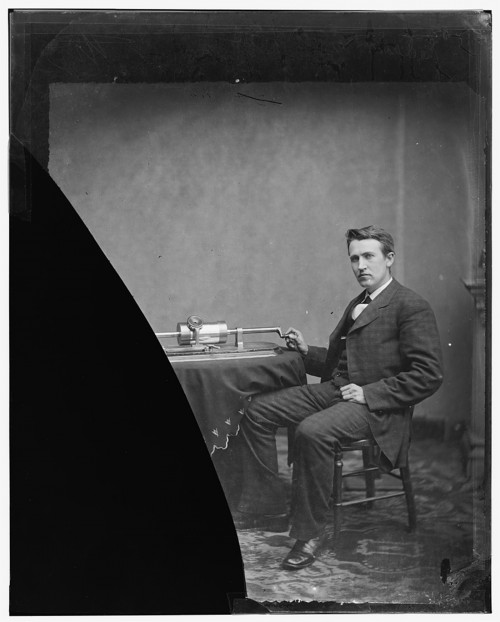

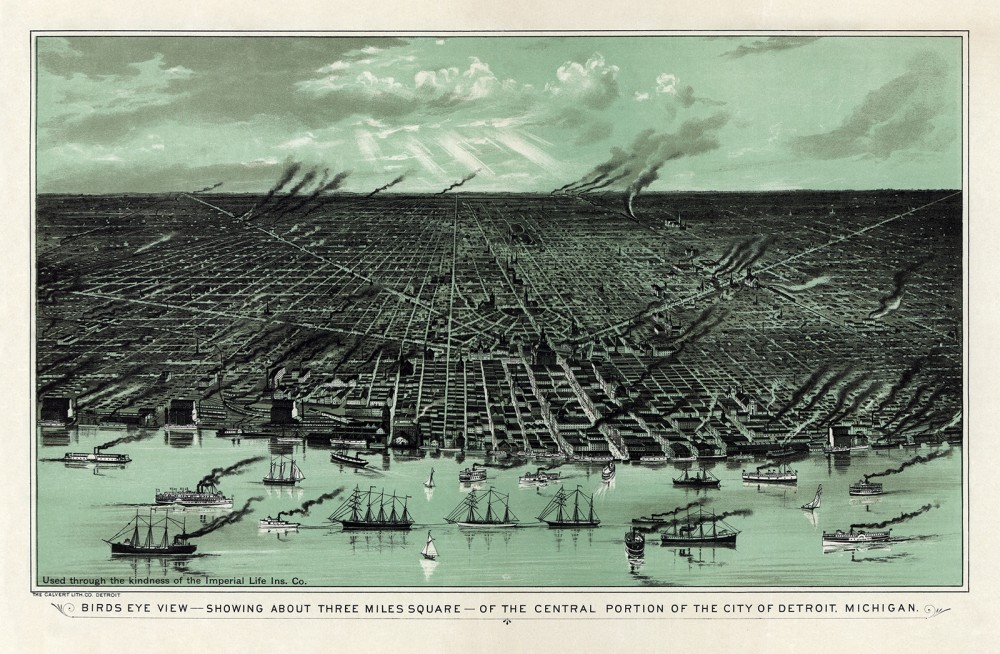

The rapid industrialization, technological advancement, and urban growth of the 1870s and 1880s triggered major changes in the way businesses structured themselves. The “second industrial revolution,” made possible by the available natural resources, growth in the labor supply through immigration, increasing capital, new legal economic entities, novel production strategies, and a growing national market, was commonly asserted to be the natural product of the federal government’s laissez faire, or “hands off,” economic policy. An unregulated business climate, the argument went, allowed for the growth of major trusts, most notably Andrew Carnegie’s Carnegie Steel (later consolidated with other producers as U.S. Steel) and John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. Each displayed the vertical and horizontal integration strategies common to the new trusts: Carnegie first utilized vertical integration by controlling every phase of business (raw materials, transportation, manufacturing, distribution), and Rockefeller adhered to horizontal integration by buying out competing refineries. Once dominant in a market, critics alleged, the trusts could artificially inflate prices, bully rivals, and bribe politicians.

Between 1897 and 1904 over 4,000 companies were consolidated down into 257 corporate firms. As one historian wrote, “By 1904 a total of 318 trusts held 40% of US manufacturing assets and boasted a capitalization of $7 billion, seven times bigger than the US national debt.” With the 20th century came the age of monopoly. From such mergers and the aggressive business policies of wealthy men such as Carnegie and Rockefeller—controversial figures often referred to as “robber barons,” so named for the cutthroat stifling of economic competition and their mistreatment of their workers—and the widely accepted political corruption that facilitated it, opposition formed and pushed for regulations to reign the power of monopolies. The great corporations became a major target of reformers.

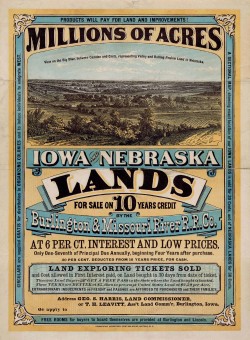

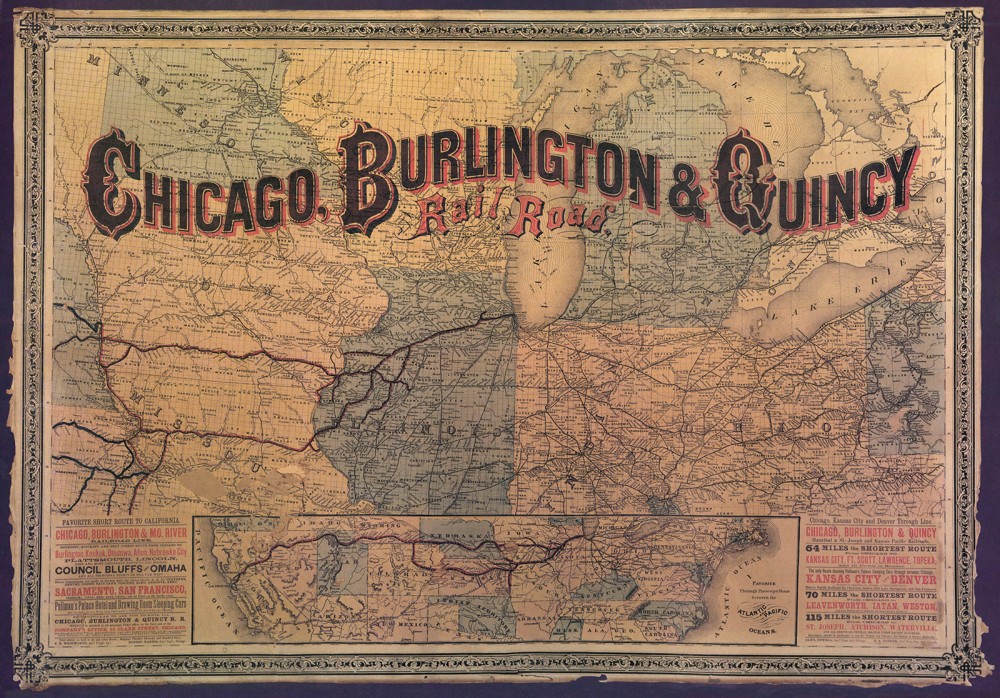

Big business, whether in meatpacking, railroads, telegraph lines, oil, or steel, posed new problems for the American legal system. Before the Civil War, most businesses operated in single state. They might ship goods across state lines or to other countries, but they typically had offices and factories in just one state. Individual states naturally regulated industry and commerce. But extensive railroad routes crossed several state lines and new mass-producing corporations operated across the nation, raising questions about where the authority to regulate such practices rested. During the 1870s, many states passed laws to check the growing power of vast new corporations. In the Midwest, so-called “Granger laws” (spurred by farmers who formed a network of organizations that were part political pressure group, part social club, and part mutual-aid society that became known as “the Grange”) regulated railroads and other new companies. Railroads and others opposed these regulations for restraining profits and, also, because of the difficulty of meeting the standards of 50 separate state regulatory laws. In 1877, the United States Supreme Court upheld these laws in a series of rulings, finding in cases such as Munn v. Illinois and Stone v. Wisconsin that railroads, and other companies of such size necessarily affected the public interest and could thus be regulated by individual states. In Munn, the court declared that “Property does become clothed with a public interest when used in a manner to make it of public consequence, and affect the community at large. When, therefore, one devoted his property to a use in which the public has an interest, he, in effect, grants to the public an interest in that use, and must submit to be controlled by the public for the common good, to the extent of the interest he has thus created.”

Later rulings, however, conceded that only the federal government could constitutionally regulate interstate commerce and the new national businesses operating it. And as more and more power and capital and market share flowed to the great corporations, the onus of regulation passed to the federal government. In 1887 Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act, which established the Interstate Commerce Commission to stop discriminatory and predatory pricing practices. The Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 aimed to limit anticompetitive practices, such as those institutionalized in cartels and monopolistic corporations. It declared a “trust …or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce… is declared to be illegal” and that those who “monopolize…any part of the trade or commerce…shall be deemed guilty.” The Sherman Anti-Trust Act declared that not all monopolies were illegal, only those that “unreasonably” stifled free trade. The courts seized on the law’s vague language, however, and the Act was turned against itself, manipulated and used, for instance, to limit the growing power of labor unions. Only in 1914, with the Clayton Anti-Trust Act, did Congress attempt to close loop holes in previous legislation.

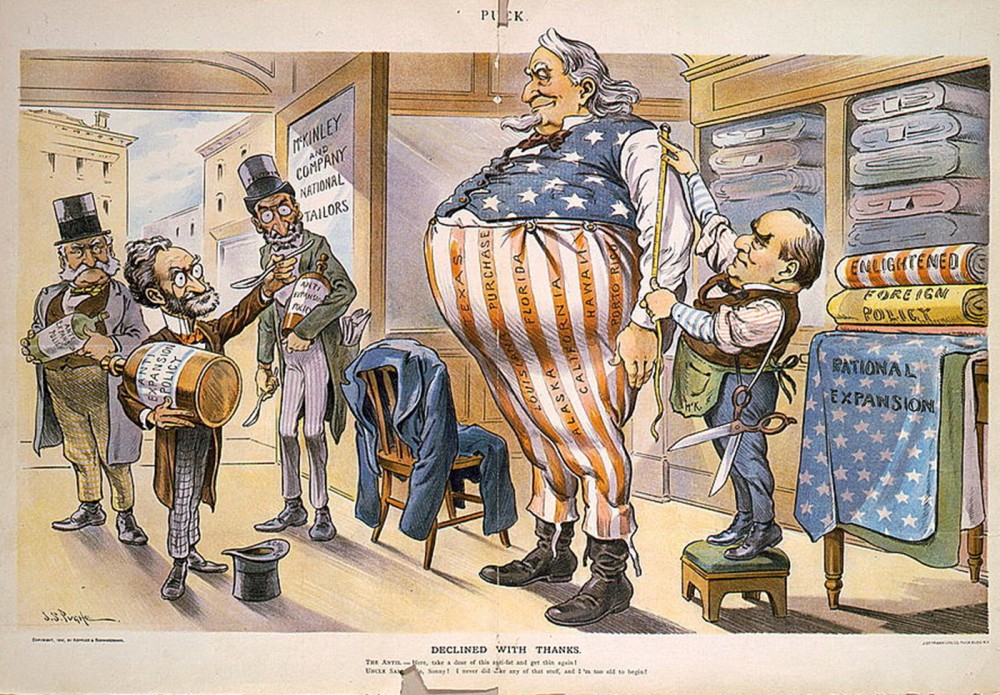

Aggression against the trusts—and the progressive vogue for “trust busting”—took on new meaning under the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. A reform Republican who ascended to the presidency after the death of William McKinley in 1901, Roosevelt’s youthful energy and confrontational politics captivated the nation. The writer Henry Adams said that he “showed the singular primitive quality that belongs to ultimate matter—the quality that medieval theology assigned to God—he was pure act.” Roosevelt was by no means anti-business. Instead, je envisioned his presidency as a mediator between opposing forces, for example, between labor unions and corporate executives. Despite his own wealthy background, Roosevelt pushed for anti-trust legislation and regulations, arguing that the courts could not be relied upon to break up the trusts. Roosevelt also used his own moral judgment to determining which monopolies he would pursue. Roosevelt believed that there were good and bad trusts, necessary monopolies and corrupt ones. Although his reputation was wildly exaggerated, he was first major national politician to go after the trusts.

“The great corporations which we have grown to speak of rather loosely as trusts are the creatures of the State, and the State not only has the right to control them, but it is in duty bound to control them wherever the need of such control is shown.” Teddy Roosevelt

His first target was the Northern Securities Company, a “holding” trust in which several wealthy bankers, most famously J.P. Morgan, used to hold controlling shares in all the major railroad companies in the American Northwest. Holding trusts had emerged as a way to circumvent the Sherman Anti-Trust Act: by controlling the majority of shares, rather than the principal, Morgan and his collaborators tried to claim that it was not a monopoly. Roosevelt’s administration sued and won in court and in 1904 the Northern Securities Company was ordered to disband into separate competitive companies. Two years later, in 1906, Roosevelt signed the Hepburn Act, allowing the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate best practices and set reasonable rates for the railroads.

Roosevelt was more interested in regulating corporations than breaking them apart. Besides, the courts were slow and unpredictable. However, his successor after 1908, William Howard Taft, firmly believed in court-oriented trust-busting and during his four years in office more than doubled the quantity of monopoly break-ups that occurred during Roosevelt’s seven years in office. Taft notably went after Carnegie’s U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation formed from the consolidation of nearly every major American steel producer.

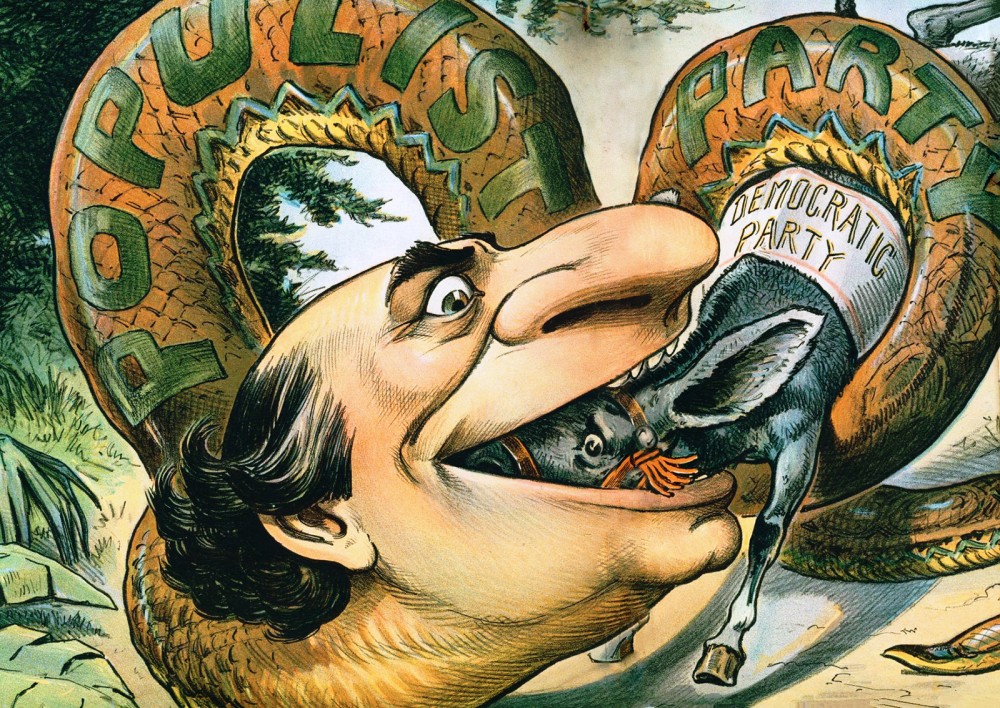

Trust-busting and the handling of monopolies dominated the election of 1912. When the Republican Party spurned Roosevelt’s return to politics and renominated the incumbent Taft, Roosevelt left and formed his own coalition, the Progressive, or “Bull-Moose,” Party. Whereas Taft took an all-encompassing view on the illegality of monopolies, Roosevelt adopted a “New Nationalism” program, which once again emphasized the regulation of already existing corporations, or, the expansion of federal power over the economy. In contrast, Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic Party nominee, emphasized in his “New Freedom” agenda neither trust-busting or federal regulation but rather small business incentives so that individual companies could increase their competitive chances. Yet once he won the election, Wilson edged near to Roosevelt’s position, signing the Clayton Anti-Trust Act of 1914. The Clayton Anti-Trust Act substantially enhanced the Sherman Act, specifically regulating mergers, price discrimination, and protecting labor’s access to collective bargaining and related strategies of picketing, boycotting, and protesting. Congress further created the Federal Trade Commission to enforce the Clayton Act, ensuring at least some measure of implementation/

While the three presidents—Roosevelt, Taft and Wilson—pushed the development and enforcement of anti-trust law, their commitments were uneven, and trust-busting itself manifested the political pressure put on politicians by the workers and farmers and progressive writers who so strongly drew attention to the ramifications of trusts and corporate capital on the lives of everyday Americans.

V. Progressive Environmentalism

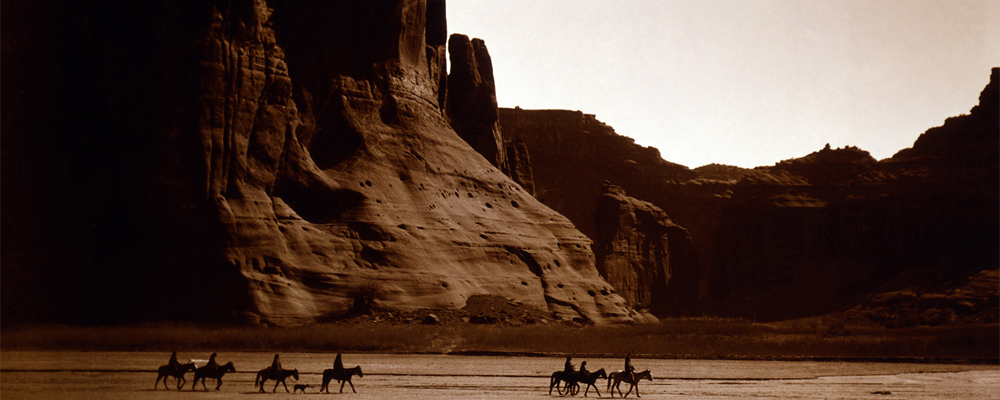

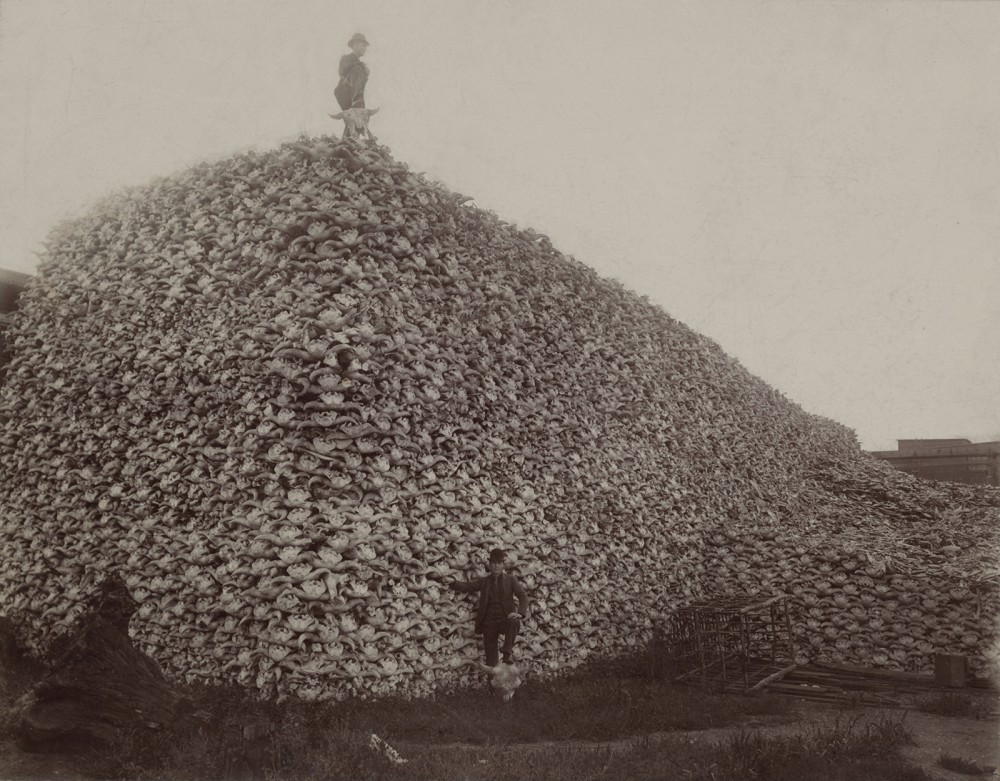

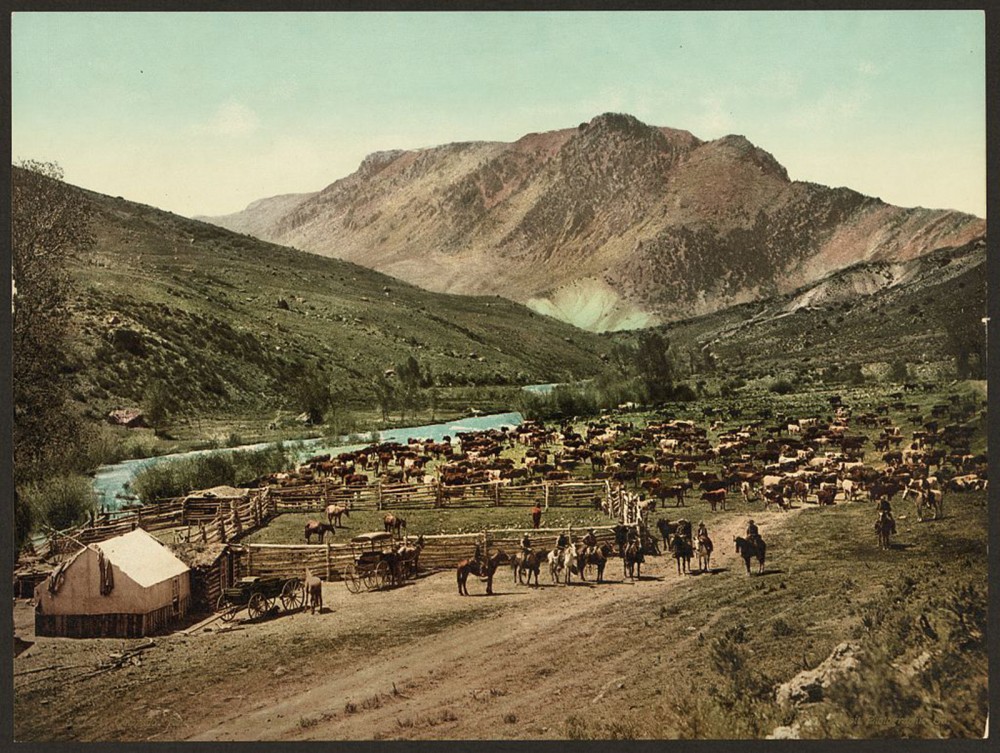

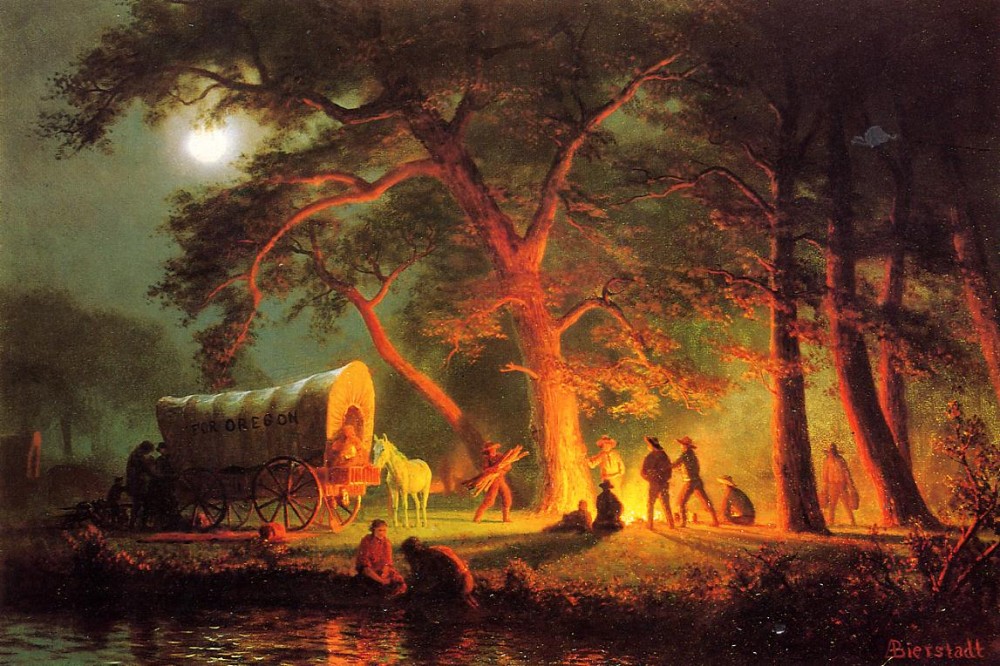

The potential scope of environmental destruction wrought by industrial capitalism was unparalleled in human history. Professional bison hunting expeditions nearly eradicated an entire species, industrialized logging companies could denude whole forests, chemical plants could pollute an entire region’s water supply. As Americans built up the West and industrialization marched ever onward, reformers embraced environmental protections.

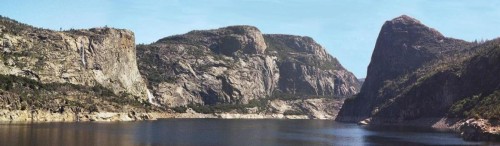

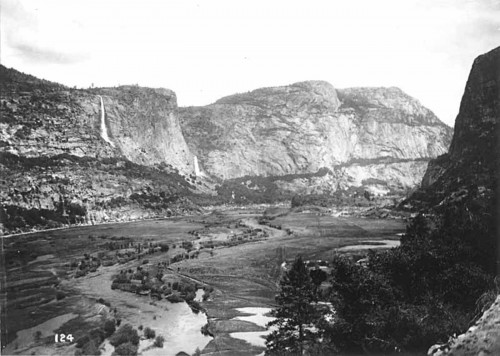

Historians often cite preservation and conservation as the two competing strategies that dueled for supremacy among environmental reformers during the Progressive Era. The tensions between these two approaches crystalized in the debate over a proposed dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley in California. The fight revolved around the provision of water for San Francisco. Engineers identified the location where the Tuolomne River ran through Hetch Hetchy as an ideal site for a reservoir. The project had been suggested in the 1880s but picked up momentum in the early twentieth century. But the valley was located inside Yosemite National Park. (Yosemite was designated a national park in 1890, though the land had been set aside earlier in a grant approved by President Lincoln in 1864.) The debate over Hetch Hetchy revealed two distinct positions on the value of the valley and on the purpose of public lands.

John Muir, a naturalist, writer, and founder of the Sierra Club, invoked the “God of the Mountains” in his defense of the valley in its supposedly pristine condition. On the other side, Gifford Pinchot, arguably the father of American forestry and a key player in the federal management of national forests, focused on what he understood to be the purpose of conservation: “to take every part of the land and its resources and put it to that use in which it will serve the most people.”Muir took a wider view of what the people needed, writing that “everybody needs beauty as well as bread.” These dueling arguments revealed the key differences in environmental thought: Muir, on the side of the preservationists, advocated setting aside pristine lands for their aesthetic and spiritual value, for those who could take his advice to “[get] in touch with the nerves of Mother Earth.”Pinchot, on the other hand, led the charge for conservation, a kind of environmental utilitarianism. Conservation was about efficient use of available resources, about planning and control, and about “the prevention of waste.” In Hetch Hetchy, conservation won out. Congress approved the project in 1913. The dam was built and the valley flooded for the benefit of San Francisco residents.

The image on the top shows the Hetch Hetchy Valley before it was dammed. The bottom photograph, taken almost a century later, shows the obvious difference after damming, with the submergence of the valley floor under the reservoir waters. Photograph of the Hetch Hetchy Valley before damming, from the Sierra Club Bulletin, January 1908. Wikimedia; Daniel Mayer (photographer), May 2002. Wikimedia.

While preservation was often articulated as an escape from an increasingly urbanized and industrialized way of life and as a welcome respite from the challenges of modernity (at least, for those who had the means to escape), the conservationists were more closely aligned with broader trends in American society. Although the “greatest good for the greatest number” was very nearly the catch phrase of conservation, conservationist policies most often benefited the nation’s financial interests. For example, many states instituted game laws to regulate hunting and protect wildlife, but laws could be entirely unbalanced. In Pennsylvania, local game laws included requiring firearm permits for non-citizens, barred hunting on Sundays, and banned the shooting of songbirds. These laws disproportionately affected Italian immigrants, critics said, as Italians often hunted songbirds for subsistence, worked in mines for low wages every day but Sunday, and were too poor to purchase permits or to pay the fines levied against them when game wardens caught them breaking these new laws. Other laws, for example, offered up resources to businesses at costs prohibitive to all but the wealthiest companies and individuals, or with regulatory requirements that could be met only by companies with extensive resources.

But it Progressive Era environmentalism was about more than the management of American public lands. After all, reformers addressing issues facing the urban poor were doing environmental work. Settlement house workers like Jane Addams and Florence Kelley focused on questions of health and sanitation, while activists concerned with working conditions, most notably Dr. Alice Hamilton, investigated both worksite hazards and occupational and bodily harm. The Progressives’ commitment to the provision of public services at the municipal level meant more coordination and oversight in matters of public health, waste management, even playgrounds and city parks. Their work focused on the intersection of communities and their material environments, highlighting the urgency of urban environmental concerns.

While reform movements focused their attention on the urban poor, other efforts targeted rural communities. The Country Life movement, spearheaded by Liberty Hyde Bailey, sought to support agrarian families and encourage young people to stay in their communities and run family farms. Early-twentieth-century educational reforms included a commitment to environmentalism at the elementary level. Led by Bailey and Anna Botsford Comstock, the nature study movement took students outside to experience natural processes and to help them develop observational skills and an appreciation for the natural world.

Other examples highlight the interconnectedness of urban and rural communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The extinction of the North American passenger pigeon reveals the complexity of Progressive Era relationships between people and nature. Passenger pigeons were actively hunted, prepared at New York’s finest restaurants and in the humblest of farm kitchens. Some hunted them for pay; others shot them in competitions at sporting clubs. And then they were gone, their ubiquity giving way only to nostalgia. Many Americans took notice at the great extinction of a species that had perhaps numbered in the billions and then was eradicated. Women in Audubon Society chapters organized against the fashion of wearing feathers—even whole birds—on ladies’ hats. Upper and middle-class women made up the lion’s share of the membership of these societies. They used their social standing to fight for birds. Pressure created national wildlife refuges and key laws and regulations that included the Lacey Act of 1900, banning the shipment of species killed illegally across state lines. Following the feathers backward, from the hats to the hunters to the birds themselves, and examining the ways women mobilized contemporary notions of womanhood in the service of protecting avian beauty, reveals a tangle of cultural and economic processes. Such examples also reveal the range of ideas, policies, and practices wrapped up in figuring out what—and who—American nature should be for.

VI. Jim Crow and African American Life

Just as reformers advocated for business regulations, anti-trust laws, environmental protections, women’s rights, and urban health campaigns, so too did many push for racial legislation in the American South. America’s tragic racial history was not erased by the Progressive Era. In fact, in all to many ways, reform removed African Americans ever farther from American public life.

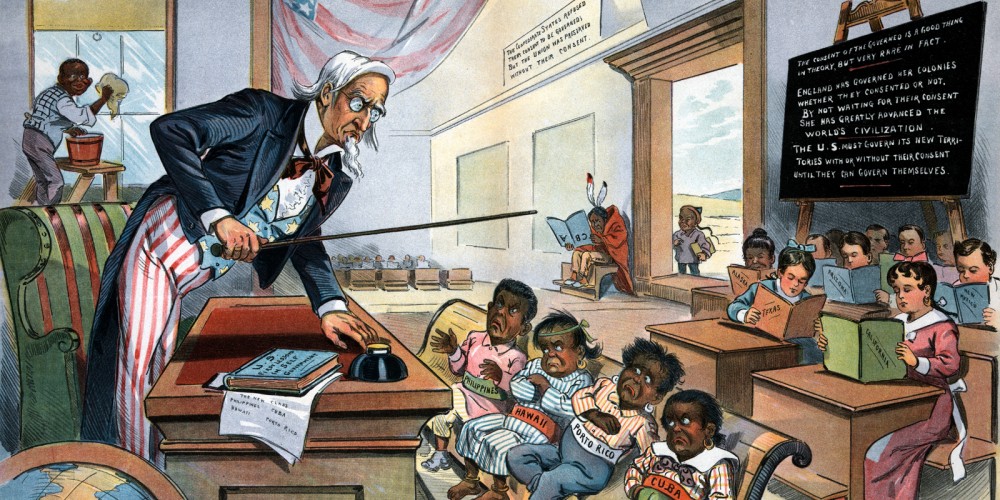

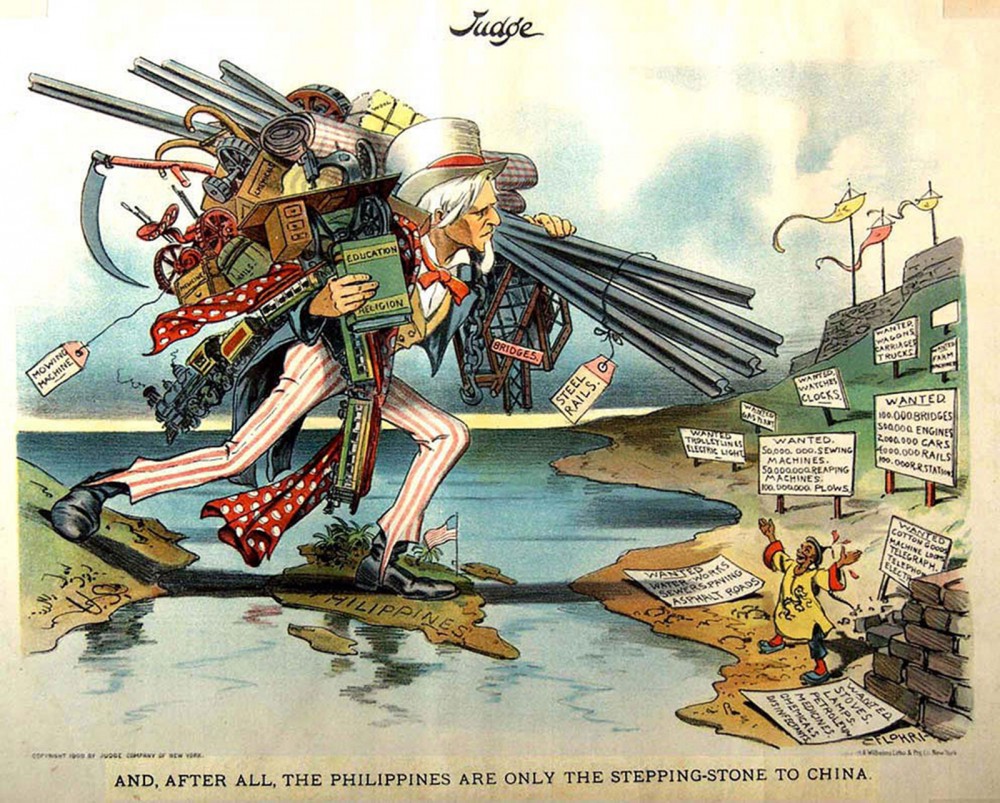

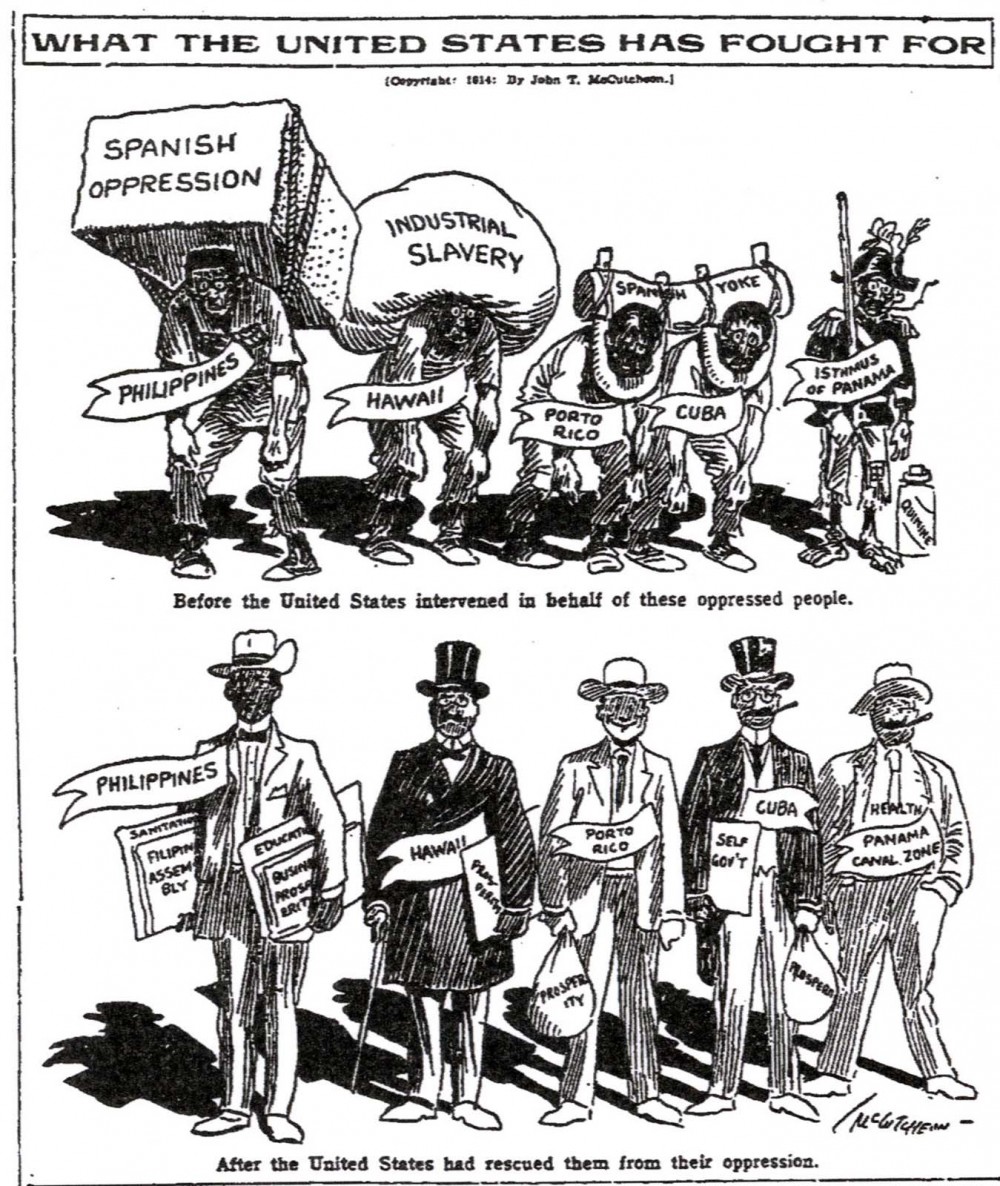

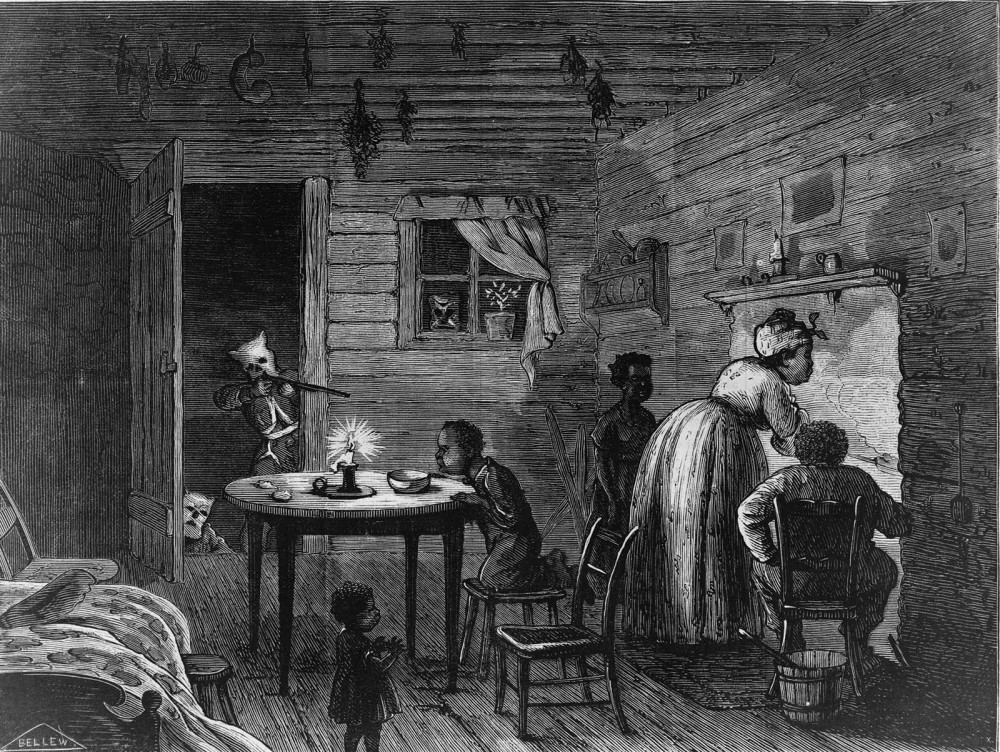

In the South, electoral politics remained a parade of electoral fraud, voter intimidation, and race-baiting. Democratic Party candidates stirred southern whites into frenzies with warnings of “negro domination” and of black men violating white women. The region’s culture of racial violence and the rise of lynching as a mass public spectacle accelerated. And as the remaining African American voters threatened the dominance of Democratic leadership in the South, southern Democrats turned to what many white southerners understood as a series of progressive electoral and social reforms—disenfranchisement and segregation. Just as reformers would clean up politics by taming city political machines, white southerners would “purify” the ballot box by restricting black voting and they would prevent racial strife by legislating the social separation of the races. The strongest supporters of such measures in the South movement were progressive Democrats and former Populists, both of whom saw in these reforms a way to eliminate the racial demagoguery that conservative Democratic party leaders had so effectively wielded. Leaders in both the North and South embraced and proclaimed the reunion of the sections on the basis of a shared Anglo-Saxon, white supremacy. As the nation took up the “white man’s burden” to uplift the world’s racially inferior peoples, the North looked to the South as an example of how to manage non-white populations. The South had become the nation’s racial vanguard.

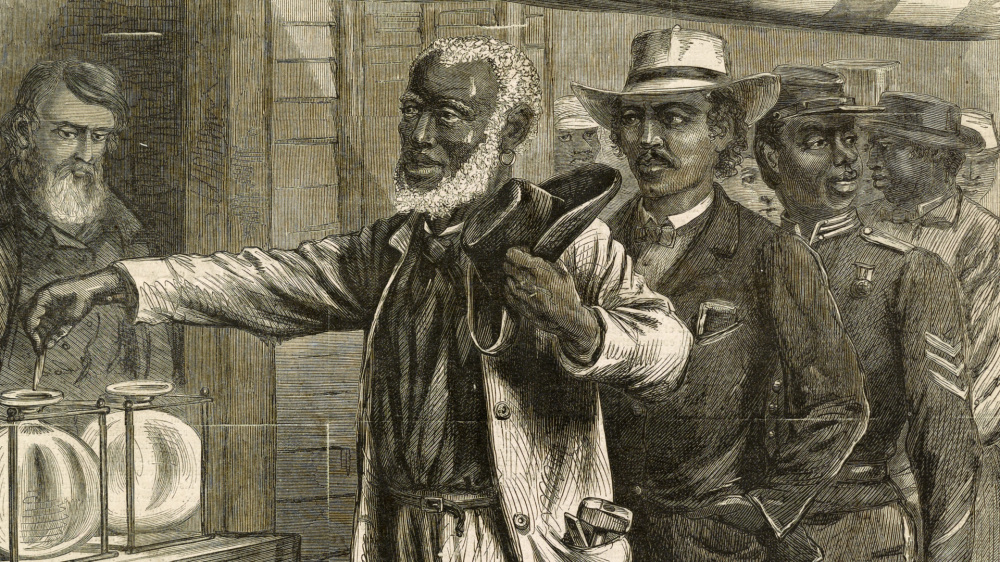

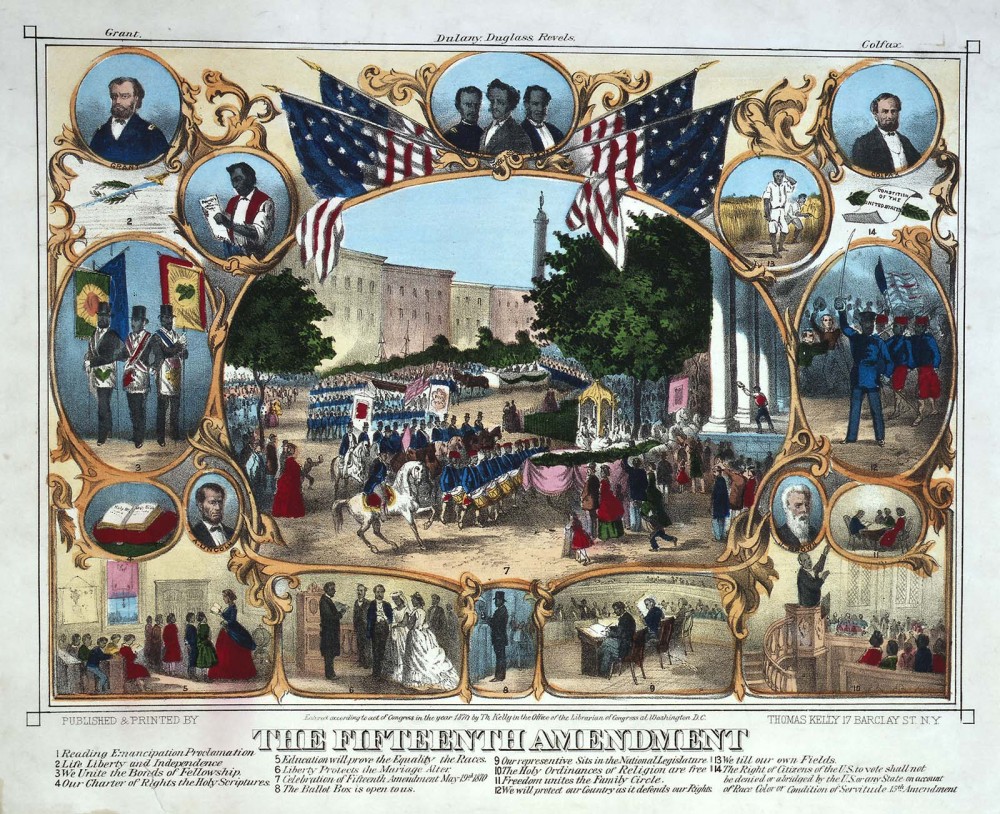

The question was how to accomplish disfranchisement. The 15th Amendment clearly prohibited states from denying any citizen the right to vote on the basis of race. In 1890 the state of Mississippi took on this legal challenge. A state newspaper called on politicians to devise “some legal defensible substitute for the abhorrent and evil methods on which white supremacy lies.” The state’s Democratic Party responded with a new state constitution designed to purge corruption at the ballot box through disenfranchisement. Those hoping to vote in Mississippi would have to jump through a series of hurdles designed with the explicit purpose of excluding the state’s African American population from political power. The state first established a poll tax, which required voters to pay for the privilege of voting. Second, it stripped the suffrage from those convicted of petty crimes most common among the state’s African Americans. Next, the state required voters to pass a literacy test. Local voting officials, who were themselves part of the local party machine, were responsible for judging whether voters were able to read and understand a section of the Constitution. In order to protect illiterate whites from exclusion, the so called “understanding clause” allowed a voter to qualify if they could adequately explain the meaning of a section that was read to them. In practice these rules were systematically abused to the point where local election officials effectively wielded the power to permit and deny suffrage at will. The disenfranchisement laws effectively moved electoral conflict from the ballot box, where public attention was greatest, to the voting registrar, where supposedly color-blind laws allowed local party officials to deny the ballot without the appearance of fraud.

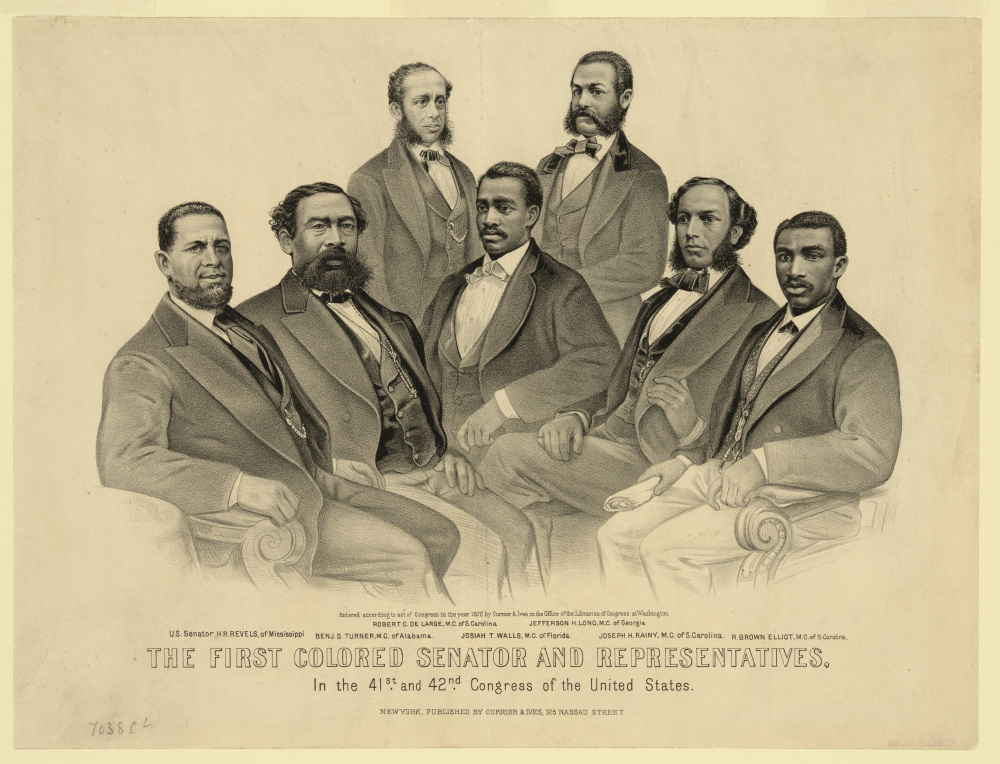

Between 1895 and 1908 the rest of the states in the South approved new constitutions including these disenfranchisement tools. Six southern states also added a grandfather clause, which bestowed the suffrage on anyone whose grandfather was eligible to vote in 1867. This ensured that whites who would have been otherwise excluded would still be eligible, at least until it was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1915. Finally, each southern state adopted an all-white primary, excluded blacks from the Democratic primary, the only political contests that mattered across much of the South.

For all the legal double-talk, the purpose of these laws was plain. James Kimble Vardaman, later Governor of Mississippi, boasted “there is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. Mississippi’s constitutional convention was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics; not the ignorant—but the nigger.” These technically colorblind tools did their work well. In 1900 Alabama had 121,159 literate black men of voting age. Only 3,742 were registered to vote. Louisiana had 130,000 black voters in the contentious election of 1896. Only 5,320 voted in 1900. Blacks were clearly the target of these laws, but that did not prevent some whites from being disenfranchised as well. Louisiana dropped 80,000 white voters over the same period. Most politically engaged southern whites considered this a price worth paying in order to prevent the fraud that had plagued the region’s elections.

At the same time that the South’s Democratic leaders were adopting the tools to disenfranchise the region’s black voters, these same legislatures were constructing a system of racial segregation even more pernicious. While it built on earlier practice, segregation was primarily a modern and urban system of enforcing racial subordination and deference. In rural areas, white and black southerners negotiated the meaning of racial difference within the context of personal relationships of kinship and patronage. An African American who broke the local community’s racial norms could expect swift personal sanction that often included violence. The crop lien and convict lease systems were the most important legal tools of racial control in the rural South. Maintaining white supremacy there did not require segregation. Maintaining white supremacy within the city, however, was a different matter altogether. As the region’s railroad networks and cities expanded, so too did the anonymity and therefore freedom of southern blacks. Southern cities were becoming a center of black middle class life that was an implicit threat to racial hierarchies. White southerners created the system of segregation as a way to maintain white supremacy in restaurants, theaters, public restrooms, schools, water fountains, train cars, and hospitals. Segregation inscribed the superiority of whites and the deference of blacks into the very geography of public spaces.

As with disenfranchisement, segregation violated a plain reading of the constitution—in this case the Fourteenth Amendment. Here the Supreme Court intervened, ruling in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) that the Fourteenth Amendment only prevented discrimination directly by states. It did not prevent discrimination by individuals, businesses, or other entities. Southern states exploited this interpretation with the first legal segregation of railroad cars in 1888. In a case that reached the Supreme Court in 1896, New Orleans resident Homer Plessy challenged the constitutionality of Louisiana’s segregation of streetcars. The court ruled against Plessy and, in the process, established the legal principle of separate but equal. Racially segregated facilities were legal provided they were equivalent. In practice this was rarely the case. The court’s majority defended its position with logic that reflected the racial assumptions of the day. “If one race be inferior to the other socially,” the court explained, “the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” Justice John Harlan, the lone dissenter, countered, “our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law” Harlan went on to warn that the court’s decision would “permit the seeds of race hatred to be planted under the sanction of law.” In their rush to fulfill Harlan’s prophecy, southern whites codified and enforced the segregation of public spaces.

Segregation was built on a fiction—that there could be a white South socially and culturally distinct from African Americans. Its legal basis rested on the constitutional fallacy of “separate but equal.” Southern whites erected a bulwark of white supremacy that would last for nearly sixty years. Segregation and disenfranchisement in the South rejected black citizenship and relegated black social and cultural life to segregated spaces. African Americans lived divided lives, acting the part whites demanded of them in public, while maintaining their own world apart from whites. This segregated world provided a measure of independence for the region’s growing black middle class, yet at the cost of poisoning the relationship between black and white. Segregation and disenfranchisement created entrenched structures of racism that completed the total rejection of the promises of Reconstruction.

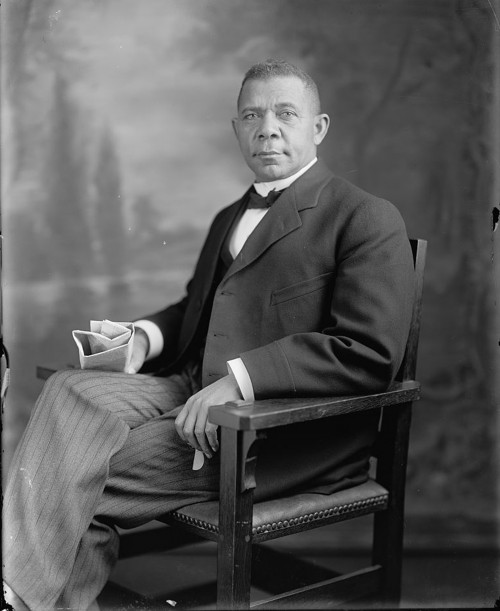

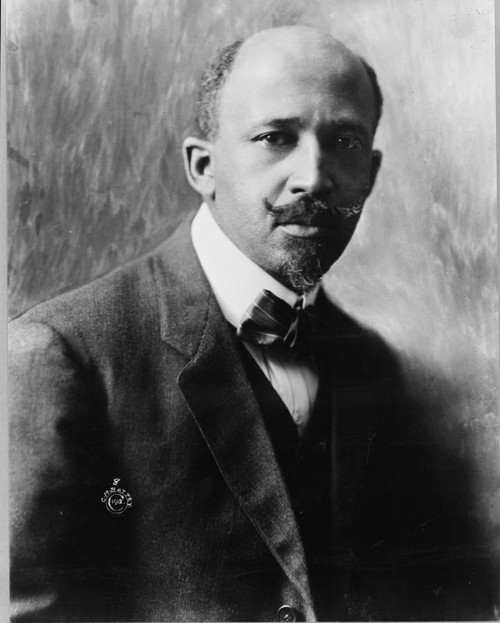

And yet, many black Americans of the Progressive Era fought back. Just as activists such as Ida Wells worked against southern lynching, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois vied for leadership among African American activists, resulting in years of intense rivalry and debated strategies for the uplifting of black Americans.

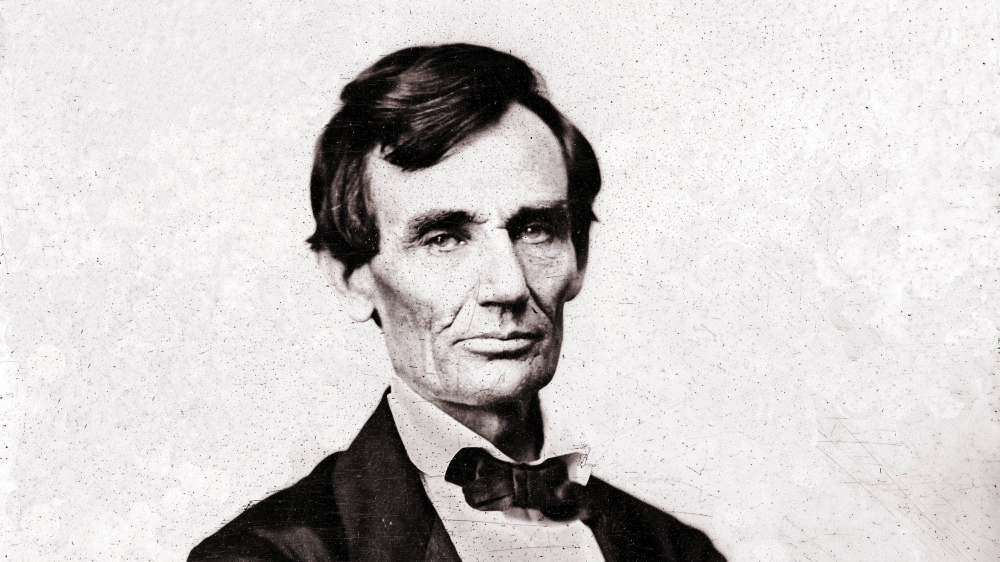

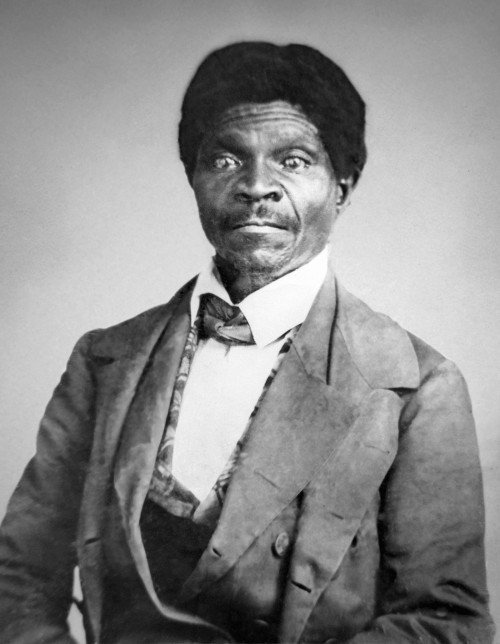

Born into the world of bondage in Virginia in 1856, Booker Taliaferro Washington was subjected to the degradation and exploitation of slavery early in life. But Washington also developed an insatiable thirst to learn. Working against tremendous odds, Washington matriculated into Hampton University in Virginia and thereafter established a southern institution that would educate many black Americans, the Tuskegee Institute. Located in Alabama, Washington envisioned Tuskegee’s contribution to black life to come through industrial education and vocational training. He believed that such skills would help African Americans too accomplish economic independence while developing a sense of self-worth and pride of accomplishment, even while living within the putrid confines of Jim Crow. Washington poured his life into Tuskegee, and thereby connected with leading white philanthropic interests. Individuals such as Andrew Carnegie, for instance, financially assisted Washington and his educational ventures.

The strategies of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois differed, but their desire remained the same: better lives for African Americans. Harris & Ewing, “WASHINGTON BOOKER T,” between 1905 and 1915. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/hec2009002812/.

As a leading spokesperson for black Americans at the turn of the twentieth century, particularly after Frederick Douglass’s exit from the historical stage in early 1895, Washington’s famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech from that same year encouraged black Americans to “cast your bucket down” to improve life’s lot under segregation. In the same speech, delivered one year before the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision that legalized segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine, Washington said to white Americans, “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Both praised as a race leader and pilloried as an accommodationist to America’s unjust racial hierarchy, Washington’s public advocacy of a conciliatory posture towards white supremacy concealed the efforts to which Washington went to assist African Americans in the legal and economic quest for racial justice. In addition to founding Tuskegee, Washington also published a handful of influential books, including the autobiography Up from Slavery (1901). Like Du Bois, Washington was also active in black journalism, working to fund and support black newspaper publications, most of which sought to counter Du Bois’s growing influence. Washington died in 1915, during World War I, of ill health in Tuskegee, Alabama.

Speaking decades later, W.E.B. DuBois said Washington had, in his 1895 “Compromise” speech, “implicitly abandoned all political and social rights. . . I never thought Washington was a bad man . . . I believed him to be sincere, though wrong.” Du Bois would directly attack Washington in his classic 1903 The Souls of Black Folk, but at the turn of the century he could never escape the shadow of his longtime rival. “I admired much about him,” Du Bois admitted, “Washington . . . died in 1915. A lot of people think I died at the same time.”

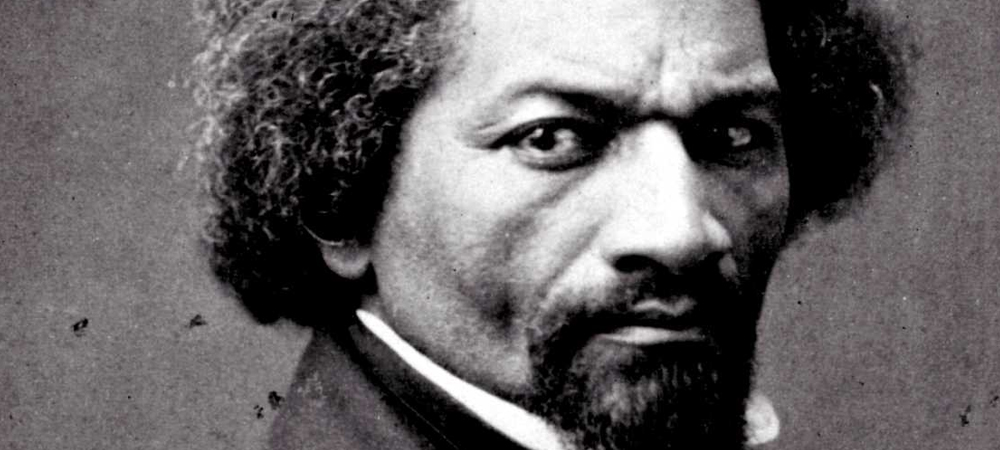

Du Bois’s criticism reveals the politicized context of the black freedom struggle and exposes the many positions available to black activists. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1868, W. E. B. Du Bois entered the world as a free person of color three years after the Civil War ended. Raised by a hardworking and independent mother, Du Bois’s New England childhood alerted him to the reality of race even as it invested the emerging thinker with an abiding faith in the power of education. Du Bois graduated at the top of his high school class and attended Fisk University. Du Bois’s sojourn to the South in 1880s left a distinct impression that would guide his life’s work to study what he called the “Negro problem,” the systemic racial and economic discrimination that Du Bois prophetically pronounced would be the problem of the twentieth century. After Fisk, Du Bois’s educational path trended back North, and he attended Harvard, earned his second degree, crossed the Atlantic for graduate work in Germany, and circulated back to Harvard and in 1895—the same year as Washington’s famous Atlanta address—became the first black American to receive a Ph.D. there.

“W.E.B. (William Edward Burghardt) Du Bois,” 1919. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003681451/.

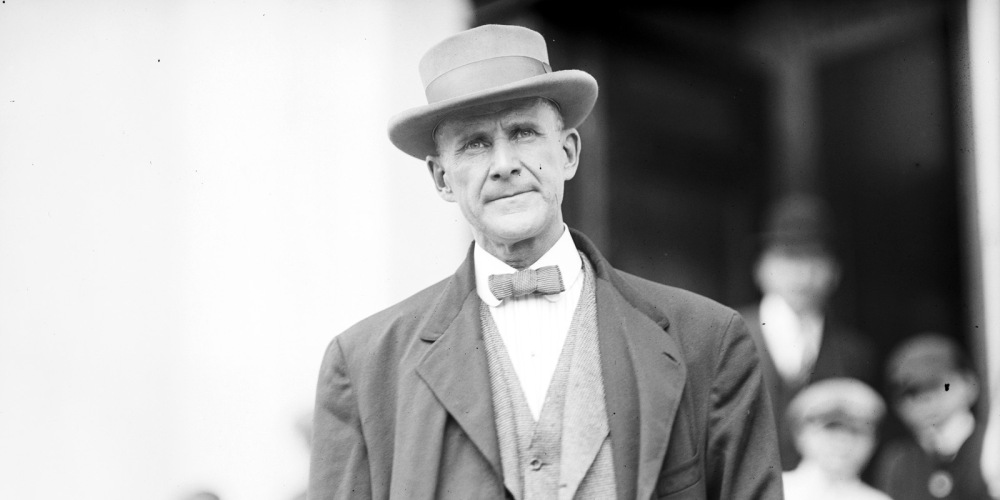

Du Bois became one of America’s foremost intellectual leaders on questions of social justice by producing scholarship that underscored the humanity of African Americans. Du Bois’s work as an intellectual, scholar, and college professor began during the Progressive Era, a time in American history marked by rapid social and cultural change as well as complex global political conflicts and developments. Du Bois addressed these domestic and international concerns not only his classrooms at Wilberforce University in Ohio and Atlanta University in Georgia, but also in a number of his early publications on the history of the transatlantic slave trade and black life in urban Philadelphia. The most well-known of these early works included The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Darkwater (1920). In these books, Du Bois combined incisive historical analysis with engaging literary drama to validate black personhood and attack the inhumanity of white supremacy, particularly in the lead up to and during World War I. In addition to publications and teaching, Du Bois set his sights on political organizing for civil rights, first with the Niagara Movement and later with its offspring the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Du Bois’s main work with the NAACP lasted from 1909 to 1934 as editor of The Crisis, one of America’s leading black publications. DuBois attacked Washington and urged black Americans to concede to nothing, to make no compromises and advocate for equal rights under the law. Throughout his early career, he pushed for civil rights legislation, launched legal challenges against discrimination, organized protests against injustice, and applied his capacity for clear research and sharp prose to expose the racial sins of Progressive Era America.

“We refuse to allow the impression to remain that the Negro-American assents to inferiority, is submissive under oppression and apologetic before insults… Any discrimination based simply on race or color is barbarous, we care not how hallowed it be by custom, expediency or prejudice … discriminations based simply and solely on physical peculiarities, place of birth, color of skin, are relics of that unreasoning human savagery of which the world is and ought to be thoroughly ashamed … Persistent manly agitation is the way to liberty.” W.E.B. DuBois

W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington made a tremendous historical impact and left a notable historical legacy. Reared in different settings, early life experiences and even personal temperaments oriented both leader’s lives and outlooks in decidedly different ways. Du Bois’s confrontational voice boldly targeted white supremacy. He believed in the power of social science to arrest the reach of white supremacy. Washington advocated incremental change for longer-term gain. He contended that economic self-sufficiency would pay off at a future date. Although Du Bois directly spoke out against Washington in the chapter “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington” in Souls of Black Folk, four years later in 1907 they shared the same lectern at Philadelphia Divinity School to address matters of race, history, and culture in the American South. As much as the philosophies of Du Bois and Washington diverged when their lives overlapped, highlighting their respective quests for racial and economic justice demonstrates the importance of understanding the multiple strategies used to demand that America live up to its democratic creed.

VII. Conclusion

Industrial capitalism unleashed powerful forces in American life. Along with wealth, technological innovation, and rising standards of living, a host of social problems unsettled many who turned to reform politics to set the world right again. The Progressive Era signaled that a turning point had been reached for many Americans who were suddenly willing to confront the age’s problems with national political solutions. Reformers sought to bring order to chaos, to bring efficiency to inefficiency, and to bring justice to injustice. Causes varied, constituencies shifted, and the tangible effects of so much energy was difficult to measure, but the Progressive Era signaled a bursting of long-simmering tensions and introduced new patterns in the relationship between American society, American culture, and American politics.

This chapter was edited by Mary Anne Henderson, with content contributions by Andrew C. Baker, Peter Catapano, Blaine Hamilton, Mary Anne Henderson, Amanda Hughett, Amy Kohout, Maria Montalvo, Brent Ruswick, Philip Luke Sinitiere, Nora Slonimsky, Whitney Stewart, and Brandy Thomas Wells.

![Conservative William McKinley promised prosperity to ordinary Americans through his “sound money” initiative, a policy he ran on during his election campaigns in 1896 and again in 1900. This election poster touts McKinley’s gold standard policy as bringing “Prosperity at Home, Prestige Abroad.” “Prosperity at home, prestige abroad,” [between 1895 and 1900]. Library of Congress,.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/18_McKinley_LC-USZC4-1329-1000x562.jpg)

![Buffalo Soldiers, the nickname given to African-American cavalrymen by the native Americans they fought, were the first peacetime all-black regiments in the regular United States army. These soldiers regularly confronted racial prejudice from other Army members and civilians, but were an essential part of American victories during the Indian Wars of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “[Buffalo soldiers of the 25th Infantry, some wearing buffalo robes, Ft. Keogh, Montana] / Chr. Barthelmess, photographer, Fort Keogh, Montana,” 1890. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98501226/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/11406v-1000x635.jpg)

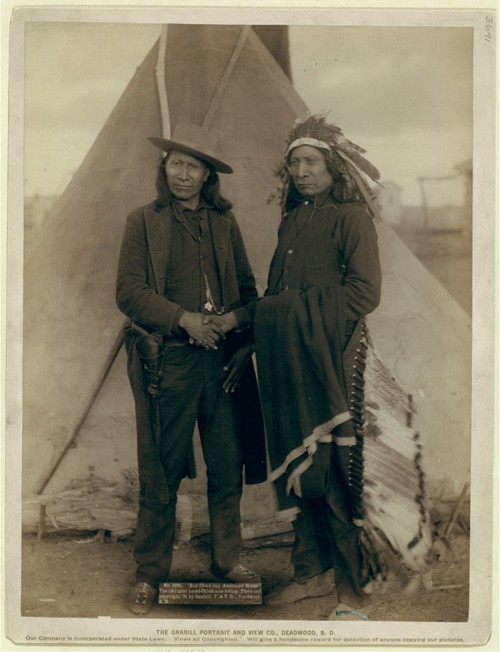

![This photograph, taken only two years after the establishment of South Dakota, shows the dire situation of the Lakota people on what was formerly their own land. John C. Grabill, “[A young Oglala girl sitting in front of a tipi, with a puppy beside her, probably on or near Pine Ridge Reservation],” 1891. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99613799/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/02515v-500x658.jpg)

![American frontierswoman and professional scout Martha Jane Canary was better known to America as Calamity Jane. A figure in western folklore during her life and after, Calamity Jane was a central character in many of the increasingly popular novels and films that romanticized western life in the twentieth century. “[Martha Canary, 1852-1903, ("Calamity Jane"), full-length portrait, seated with rifle as General Crook's scout],” c. 1895. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005689345/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3a53082v-500x629.jpg)

![Stereoscopic view of the Great Union Stockyards in turn-of-the-century Chicago. The stockyards were the epicenter of the American meat-packing industry for much of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The yards were made possible through the joint purchase of over three acres of unuseable swamp land by railroad companies, who then turned it into a hugely profitable centralized meatpacking district. In the Great Union Stock Yards [stockyards], Chicago, U.S.A., c. 1890. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:In_the_Great_Union_Stock_Yards_%28stockyards%29,_Chicago,_U.S.A,_from_Robert_N._Dennis_collection_of_stereoscopic_views_3.png.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/In_the_Great_Union_Stock_Yards_stockyards_Chicago_U.S.A_from_Robert_N._Dennis_collection_of_stereoscopic_views_3-1000x515.png)

![Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton maintained a strong and productive relationship for nearly half a century as they sought to secure political rights for women. While the fight for women’s rights stalled during the war, it sprung back to life as Anthony, Stanton, and others formed the American Equal Rights Association. “[Elizabeth Cady Stanton, seated, and Susan B. Anthony, standing, three-quarter length portrait],” between 1880 and 1902. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97500087/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3a02558v-500x695.jpg)

![War brought destruction across the South. Governmental and private buildings, communication systems, the economy, and transportation infrastructure were all debilitated. “[Richmond, Va. Crippled locomotive, Richmond & Petersburg Railroad depot],” c. 1865. Library of Congress.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/15_Richmond_LC-B811-3258-1000x562.jpg)

![Photography captured the horrors of war as never before. Some Civil War photographers arranged the actors in their frames to capture the best picture, even repositioning bodies of dead soldiers for battlefield photos. Alexander Gardner, “[Antietam, Md. Confederate dead by a fence on the Hagerstown road],” September 1862. Library of Congress.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/antietam-1000x562.jpg)

![The creation of black regiments was another kind of innovation during the Civil War. Northern free blacks and newly freed slaves joined together under the leadership of white officers to fight for the Union cause. This novelty was not only beneficial for the Union war effort; it also showed the Confederacy that the Union sought to destroy the foundational institution (slavery) upon which their nation was built. William Morris Smith, “[District of Columbia. Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln],” between 1863 and 1866. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000946/PP/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/04294v-1000x801.jpg)

![This African American family dressed in their finest clothes (including a USCT uniform) for this photograph, projecting respectability and dignity that was at odds with the southern perception of black Americans. “[Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform with wife and two daughters],” between 1863 and 1865. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010647216/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/36454v-1000x845.jpg)

![The slave markets of the South varied in size and style, but the St. Louis Exchange in New Orleans was so frequently described it became a kind of representation for all southern slave markets. Indeed, the St. Louis Hotel rotunda was cemented in the literary imagination of nineteenth-century Americans after Harriet Beecher Stowe chose it as the site for the sale of Uncle Tom in her 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. After the ruin of the St. Clare plantation, Tom and his fellow slaves were suddenly property that had to be liquidated. Brought to New Orleans to be sold to the highest bidder, Tom found himself “[b]eneath a splendid dome” where “men of all nations” scurried about. J. M. Starling (engraver), "Sale of estates, pictures and slaves in the rotunda, New Orleans,” 1842. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans.jpg.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans-1000x732.jpg)