Supporters of defeated U.S. President Donald Trump cheer the breaching of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Via Wikimedia.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

The U.S. Capitol was stormed on January 6, 2021. Thousands of right-wing protestors, fueled by an onslaught of lies and fabrications and conspiracy theories surrounding the November 2020 elections, rallied that morning in front of the White House to “Stop the Steal.” Repeating a familiar litany of lies and distortions, the sitting president of the United States then urged them to march on the Capitol and stop the certification of the November electoral vote. “You’ll never take back our country with weakness,” he said. “Fight like hell,” he said. “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”1 And so they did. They marched on the capitol, armed themselves with metal pipes, baseball bats, hockey sticks, pepper spray, stun guns, and flag poles, and attacked the police officers barricading the building.

“It was like something from a medieval battle,” Capitol Police Officer Aquilino Gonell recalled 2 The mob pulled D.C. Metropolitan Police Officer Michael Fanone into the crowd, beat him with flagpoles, and tasered him. “Kill him with his own gun,” Fanone remembered the mob shouting just before he lost consciousness. “I can still hear those words in my head today,” he testified six months later.3

The mob breached the barriers and poured into the building, marking perhaps the greatest domestic assault on the American federal government since the Civil War. But the events of January 6 were rooted in history.

Revolutionary technological change, unprecedented global flows of goods and people and capital, an amorphous decades-long War on Terror, accelerating inequality, growing diversity, a changing climate, political stalemate: our present is not an island of circumstance but a product of history. Time marches forever on. The present becomes the past, but, as William Faulkner famously put it, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”4 The last several decades of American history have culminated in the present, an era of innovation and advancement but also of stark partisan division, racial and ethnic tension, protests, gender divides, uneven economic growth, widening inequalities, military interventions, bouts of mass violence, and pervasive anxieties about the present and future of the United States. Through boom and bust, national tragedy, foreign wars, and the maturation of a new generation, a new chapter of American history is busy being written.

II. American Politics before September 11, 2001

The conservative Reagan Revolution lingered over the presidential election of 1988. At stake was the legacy of a newly empowered conservative movement, a movement that would move forward with Reagan’s vice president, George H. W. Bush, who triumphed over Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis with a promise to continue the conservative work that had commenced in the 1980s.

The son of a U.S. senator from Connecticut, George H. W. Bush was a World War II veteran, president of a successful oil company, chair of the Republican National Committee, director of the CIA, and member of the House of Representatives from Texas. After failing to best Reagan in the 1980 Republican primaries, he was elected as his vice president in 1980 and again in 1984. In 1988, Michael Dukakis, a proud liberal from Massachusetts, challenged Bush for the White House.

Dukakis ran a weak campaign. Bush, a Connecticut aristocrat who had never been fully embraced by movement conservatism, particularly the newly animated religious right, nevertheless hammered Dukakis with moral and cultural issues. Bush said Dukakis had blocked recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in Massachusetts schools and that he was a “card-carrying member” of the ACLU. Bush meanwhile dispatched his eldest son, George W. Bush, as his ambassador to the religious right.5 Bush also infamously released a political ad featuring the face of Willie Horton, a Black Massachusetts man and convicted murderer who raped a woman after being released through a prison furlough program during Dukakis’s tenure as governor. “By the time we’re finished,” Bush’s campaign manager, Lee Atwater, said, “they’re going to wonder whether Willie Horton is Dukakis’ running mate.”6 Liberals attacked conservatives for perpetuating the ugly “code word” politics of the old Southern Strategy—the underhanded appeal to white racial resentments perfected by Richard Nixon in the aftermath of civil rights legislation.7 Buoyed by such attacks, Bush won a large victory and entered the White House.

Bush’s election signaled Americans’ continued embrace of Reagan’s conservative program and further evidenced the utter disarray of the Democratic Party. American liberalism, so stunningly triumphant in the 1960s, was now in full retreat. It was still, as one historian put it, the “Age of Reagan.”8

The Soviet Union collapsed during Bush’s tenure. Devastated by a stagnant economy, mired in a costly and disastrous war in Afghanistan, confronted with dissident factions in Eastern Europe, and rocked by internal dissent, the Soviet Union crumbled. Soviet leader and reformer Mikhail Gorbachev loosened the Soviet Union’s tight personal restraints and censorship (glasnost) and liberalized the Soviet political machinery (perestroika). Eastern Bloc nations turned against their communist organizations and declared their independence from the Soviet Union. Gorbachev let them go. Soon, the Soviet Union unraveled. On December 25, 1991, Gorbachev resigned his office, declaring that the Soviet Union no longer existed. At the Kremlin—Russia’s center of government—the new tricolor flag of the Russian Federation was raised.9

The dissolution of the Soviet Union left the United States as the world’s only remaining superpower. Global capitalism seemed triumphant. Observers wondered if some final stage of history had been reached, if the old battles had ended and a new global consensus built around peace and open markets would reign forever. “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such,” wrote Francis Fukuyama in his much-talked-about 1989 essay, “The End of History?”10 Assets in Eastern Europe were privatized and auctioned off as newly independent nations introduced market economies. New markets were rising in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe. India, for instance, began liberalizing its economic laws and opening itself up to international investment in 1991. China’s economic reforms, advanced by Chairman Deng Xiaoping and his handpicked successors, accelerated as privatization and foreign investment proceeded.

The post–Cold War world was not without international conflicts, however. When Iraq invaded the small but oil-rich nation of Kuwait in 1990, Congress granted President Bush approval to intervene. The United States laid the groundwork for intervention (Operation Desert Shield) in August and commenced combat operations (Operation Desert Storm) in January 1991. With the memories of Vietnam still fresh, many Americans were hesitant to support military action that could expand into a protracted war or long-term commitment of troops. But the Gulf War was a swift victory for the United States. New technologies—including laser-guided precision bombing—amazed Americans, who could now watch twenty-four-hour live coverage of the war on the Cable News Network (CNN). The Iraqi army disintegrated after only a hundred hours of ground combat. President Bush and his advisors opted not to pursue the war into Baghdad and risk an occupation and insurgency. And so the war was won. Many wondered if the “ghosts of Vietnam” had been exorcised.11 Bush won enormous popular support. Gallup polls showed a job approval rating as high as 89 percent in the weeks after the end of the war.12

During the Gulf War, the Iraqi military set fire to Kuwait’s oil fields, many of which burned for months. March 21, 1991. Wikimedia.

President Bush’s popularity seemed to suggest an easy reelection in 1992, but Bush had still not won over the New Right, the aggressively conservative wing of the Republican Party, despite his attacks on Dukakis, his embrace of the flag and the pledge, and his promise, “Read my lips: no new taxes.” He faced a primary challenge from political commentator Patrick Buchanan, a former Reagan and Nixon White House advisor, who cast Bush as a moderate, as an unworthy steward of the conservative movement who was unwilling to fight for conservative Americans in the nation’s ongoing culture war. Buchanan did not defeat Bush in the Republican primaries, but he inflicted enough damage to weaken his candidacy.13

Still thinking that Bush would be unbeatable in 1992, many prominent Democrats passed on a chance to run, and the Democratic Party nominated a relative unknown, Arkansas governor Bill Clinton. Dogged by charges of marital infidelity and draft dodging during the Vietnam War, Clinton was a consummate politician with enormous charisma and a skilled political team. He framed himself as a New Democrat, a centrist open to free trade, tax cuts, and welfare reform. Twenty-two years younger than Bush, he was the first baby boomer to make a serious run at the presidency. Clinton presented the campaign as a generational choice. During the campaign he appeared on MTV, played the saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show, and told voters that he could offer the United States a new way forward.

Bush ran on his experience and against Clinton’s moral failings. The GOP convention in Houston that summer featured speeches from Pat Buchanan and religious leader Pat Robertson decrying the moral decay plaguing American life. Clinton was denounced as a social liberal who would weaken the American family through both his policies and his individual moral character. But Clinton was able to convince voters that his moderated southern brand of liberalism would be more effective than the moderate conservatism of George Bush. Bush’s candidacy, of course, was perhaps most damaged by a sudden economic recession. As Clinton’s political team reminded the country, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Clinton won the election, but the Reagan Revolution still reigned. Clinton and his running mate, Tennessee senator Albert Gore Jr., both moderate southerners, promised a path away from the old liberalism of the 1970s and 1980s (and the landslide electoral defeats of the 1980s). They were Democrats, but conservative Democrats, so-called New Democrats. In his first term, Clinton set out an ambitious agenda that included an economic stimulus package, universal health insurance, a continuation of the Middle East peace talks initiated by Bush’s secretary of state James A. Baker III, welfare reform, and a completion of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to abolish trade barriers between the United States, Mexico, and Canada. His moves to reform welfare, open trade, and deregulate financial markets were particular hallmarks of Clinton’s Third Way, a new Democratic embrace of heretofore conservative policies.14

With NAFTA, Clinton reversed decades of Democratic opposition to free trade and opened the nation’s northern and southern borders to the free flow of capital and goods. Critics, particularly in the Midwest’s Rust Belt, blasted the agreement for opening American workers to competition by low-paid foreign workers. Many American factories relocated and set up shops—maquilas—in northern Mexico that took advantage of Mexico’s low wages. Thousands of Mexicans rushed to the maquilas. Thousands more continued on past the border.

If NAFTA opened American borders to goods and services, people still navigated strict legal barriers to immigration. Policy makers believed that free trade would create jobs and wealth that would incentivize Mexican workers to stay home, and yet multitudes continued to leave for opportunities in el norte. The 1990s proved that prohibiting illegal migration was, if not impossible, exceedingly difficult. Poverty, political corruption, violence, and hopes for a better life in the United States—or simply higher wages—continued to lure immigrants across the border. Between 1990 and 2010, the proportion of foreign-born individuals in the United States grew from 7.9 percent to 12.9 percent, and the number of undocumented immigrants tripled from 3.5 million to 11.2. While large numbers continued to migrate to traditional immigrant destinations—California, Texas, New York, Florida, New Jersey, and Illinois—the 1990s also witnessed unprecedented migration to the American South. Among the fastest-growing immigrant destination states were Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Georgia, and North Carolina, all of which had immigration growth rates in excess of 100 percent during the decade.15

In response to the continued influx of immigrants and the vocal complaints of anti-immigration activists, policy makers responded with such initiatives as Operation Gatekeeper and Hold the Line, which attempted to make crossing the border more prohibitive. The new strategy “funneled” immigrants to dangerous and remote crossing areas. Immigration officials hoped the brutal natural landscape would serve as a natural deterrent. It wouldn’t. By 2017, hundreds of immigrants died each year of drowning, exposure, and dehydration.16

Clinton, meanwhile, sought to carve out a middle ground in his domestic agenda. In his first weeks in office, Clinton reviewed Department of Defense policies restricting homosexuals from serving in the armed forces. He pushed through a compromise plan, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, that removed any questions about sexual orientation in induction interviews but also required that gay military personnel keep their sexual orientation private. The policy alienated many. Social conservatives were outraged and his credentials as a conservative southerner suffered, while many liberals recoiled at continued antigay discrimination.

In his first term, Clinton also put forward universal healthcare as a major policy goal, and first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton played a major role in the initiative. But the push for a national healthcare law collapsed on itself. Conservatives revolted, the healthcare industry flooded the airwaves with attack ads, Clinton struggled with congressional Democrats, and voters bristled. A national healthcare system was again repulsed.

The midterm elections of 1994 were a disaster for the Democrats, who lost the House of Representatives for the first time since 1952. Congressional Republicans, led by Georgia congressman Newt Gingrich and Texas congressman Dick Armey, offered a policy agenda they called the Contract with America. Republican candidates from around the nation gathered on the steps of the Capitol to pledge their commitment to a conservative legislative blueprint to be enacted if the GOP won control of the House. The strategy worked.

Social conservatives were mobilized by an energized group of religious activists, especially the Christian Coalition, led by Pat Robertson and Ralph Reed. Robertson was a television minister and entrepreneur whose 1988 long shot run for the Republican presidential nomination brought him a massive mailing list and a network of religiously motivated voters around the country. From that mailing list, the Christian Coalition organized around the country, seeking to influence politics on the local and national level.

In 1996 the generational contest played out again when the Republicans nominated another aging war hero, Senator Bob Dole of Kansas, but Clinton again won the election, becoming the first Democrat to serve back-to-back terms since Franklin Roosevelt. He was aided in part by the amelioration of conservatives by his signing of welfare reform legislation, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, which decreased welfare benefits, restricted eligibility, and turned over many responsibilities to states. Clinton said it would “break the cycle of dependency.”17

Clinton presided over a booming economy fueled by emergent computing technologies. Personal computers had skyrocketed in sales, and the Internet became a mass phenomenon. Communication and commerce were never again the same. The tech boom was driven by business, and the 1990s saw robust innovation and entrepreneurship. Investors scrambled to find the next Microsoft or Apple, suddenly massive computing companies. But it was the Internet that sparked a bonanza. The dot-com boom fueled enormous economic growth and substantial financial speculation to find the next Google or Amazon.

Republicans, defeated at the polls in 1996 and 1998, looked for other ways to undermine Clinton’s presidency. Political polarization seemed unprecedented and a sensation-starved, post-Watergate media demanded scandal. The Republican Congress spent millions on investigations hoping to uncover some shred of damning evidence to sink Clinton’s presidency, whether it be real estate deals, White House staffing, or adultery. Rumors of sexual misconduct had always swirled around Clinton. The press, which had historically turned a blind eye to such private matters, saturated the media with Clinton’s sex scandals. Congressional investigations targeted the allegations and Clinton denied having “sexual relations” with Monica Lewinsky before a grand jury and in a statement to the American public. Republicans used the testimony to allege perjury. In December 1998, the House of Representatives voted to impeach the president. It was a wildly unpopular step. Two thirds of Americans disapproved, and a majority told Gallup pollsters that Republicans had abused their constitutional authority. Clinton’s approval rating, meanwhile, jumped to 78 percent.18 In February 1999, Clinton was acquitted by the Senate by a vote that mostly fell along party lines.

The 2000 election pitted Vice President Albert Gore Jr. against George W. Bush, the twice-elected Texas governor and son of the former president. Gore, wary of Clinton’s recent impeachment despite Clinton’s enduring approval ratings, distanced himself from the president and eight years of relative prosperity. Instead, he ran as a pragmatic, moderate liberal. Bush, too, ran as a moderate, claiming to represent a compassionate conservatism and a new faith-based politics. Bush was an outspoken evangelical. In a presidential debate, he declared Jesus Christ his favorite political philosopher. He promised to bring church leaders into government, and his campaign appealed to churches and clergy to get out the vote. Moreover, he promised to bring honor, dignity, and integrity to the Oval Office, a clear reference to Clinton. Utterly lacking the political charisma that had propelled Clinton, Gore withered under Bush’s attacks. Instead of trumpeting the Clinton presidency, Gore found himself answering the media’s questions about whether he was sufficiently an alpha male and whether he had invented the Internet.

Few elections have been as close and contentious as the 2000 election, which ended in a deadlock. Gore had won the popular vote by 500,000 votes, but the Electoral College hinged on a contested Florida election. On election night the media called Florida for Gore, but then Bush made late gains and news organizations reversed themselves by declaring the state for Bush—and Bush the probable president-elect. Gore conceded privately to Bush, then backpedaled as the counts edged back toward Gore yet again. When the nation awoke the next day, it was unclear who had been elected president. The close Florida vote triggered an automatic recount.

Lawyers descended on Florida. The Gore campaign called for manual recounts in several counties. Local election boards, Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris, and the Florida Supreme Court all weighed in until the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in and, in an unprecedented 5–4 decision in Bush v. Gore, ruled that the recount had to end. Bush was awarded Florida by a margin of 537 votes, enough to win him the state and give him a majority in the Electoral College. He had won the presidency.

In his first months in office, Bush fought to push forward enormous tax cuts skewed toward America’s highest earners. The bursting of the dot-com bubble weighed down the economy. Old political and cultural fights continued to be fought. And then the towers fell.

III. September 11 and the War on Terror

On the morning of September 11, 2001, nineteen operatives of the al-Qaeda terrorist organization hijacked four passenger planes on the East Coast. American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City at 8:46 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT). United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower at 9:03. American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the western façade of the Pentagon at 9:37. At 9:59, the South Tower of the World Trade Center collapsed. At 10:03, United Airlines Flight 93 crashed in a field outside Shanksville, Pennsylvania, brought down by passengers who had received news of the earlier hijackings. At 10:28, the North Tower collapsed. In less than two hours, nearly three thousand Americans had been killed.

Ground Zero six days after the September 11th attacks. Wikimedia, .

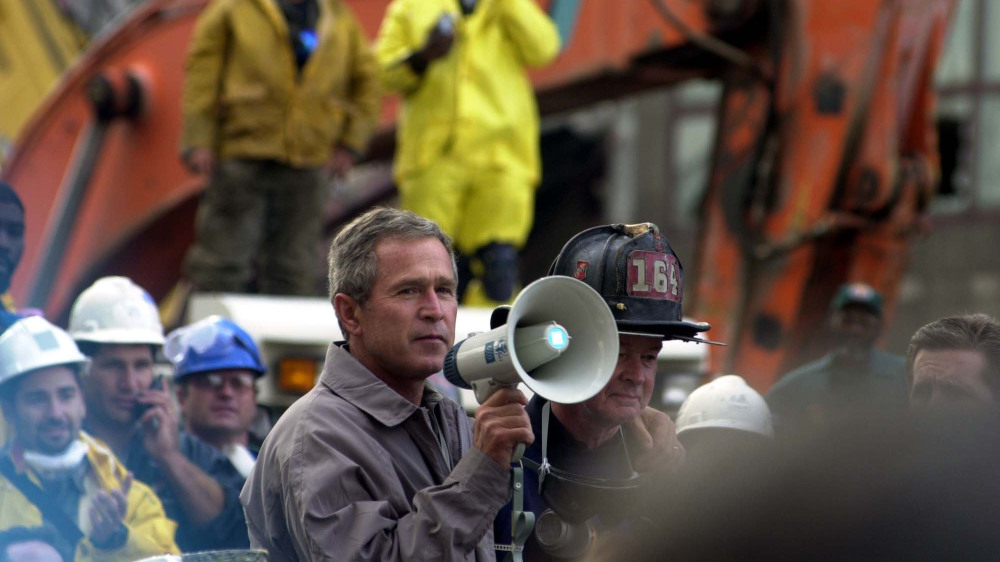

The attacks stunned Americans. Late that night, Bush addressed the nation and assured the country that “the search is under way for those who are behind these evil acts.” At Ground Zero three days later, Bush thanked first responders for their work. A worker said he couldn’t hear him. “I can hear you,” Bush shouted back, “The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.”

President Bush addresses rescue workers at Ground Zero. 2001. FEMA Photo Library.

American intelligence agencies quickly identified the radical Islamic militant group al-Qaeda, led by the wealthy Saudi Osama bin Laden, as the perpetrators of the attack. Sheltered in Afghanistan by the Taliban, the country’s Islamic government, al-Qaeda was responsible for a 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center and a string of attacks at U.S. embassies and military bases across the world. Bin Laden’s Islamic radicalism and his anti-American aggression attracted supporters across the region and, by 2001, al-Qaeda was active in over sixty countries.

Although in his presidential campaign Bush had denounced foreign nation-building, he populated his administration with neoconservatives, firm believers in the expansion of American democracy and American interests abroad. Bush advanced what was sometimes called the Bush Doctrine, a policy in which the United States would have the right to unilaterally and preemptively make war on any regime or terrorist organization that posed a threat to the United States or to U.S. citizens. It would lead the United States into protracted conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq and entangle the United States in nations across the world. Journalist Dexter Filkins called it a Forever War, a perpetual conflict waged against an amorphous and undefeatable enemy.19 The geopolitical realities of the twenty-first-century world were forever transformed.

The United States, of course, had a history in Afghanistan. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December 1979 to quell an insurrection that threatened to topple Kabul’s communist government, the United States financed and armed anti-Soviet insurgents, the Mujahideen. In 1981, the Reagan administration authorized the CIA to provide the Mujahideen with weapons and training to strengthen the insurgency. An independent wealthy young Saudi, Osama bin Laden, also fought with and funded the Mujahideen. And they began to win. Afghanistan bled the Soviet Union dry. The costs of the war, coupled with growing instability at home, convinced the Soviets to withdraw from Afghanistan in 1989.20

Osama bin Laden relocated al-Qaeda to Afghanistan after the country fell to the Taliban in 1996. Under Bill Clinton, the United States launched cruise missiles at al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan in retaliation for al-Qaeda bombings on American embassies in Africa.

After September 11, with a broad authorization of military force, Bush administration officials made plans for military action against al-Qaeda and the Taliban. What would become the longest war in American history began with the launching of Operation Enduring Freedom in October 2001. Air and missile strikes hit targets across Afghanistan. U.S. Special Forces joined with fighters in the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance. Major Afghan cities fell in quick succession. The capital, Kabul, fell on November 13. Bin Laden and al-Qaeda operatives retreated into the rugged mountains along the border of Pakistan in eastern Afghanistan. The American occupation of Afghanistan continued.

As American troops struggled to contain the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Bush administration set its sights on Iraq. After the conclusion of the Gulf War in 1991, American officials established economic sanctions, weapons inspections, and no-fly zones. By mid-1991, American warplanes were routinely patrolling Iraqi skies and coming under periodic fire from Iraqi missile batteries. The overall cost to the United States of maintaining the two no-fly zones over Iraq was roughly $1 billion a year. Related military activities in the region added almost another $500 million to the annual bill. On the ground in Iraq, meanwhile, Iraqi authorities clashed with UN weapons inspectors. Iraq had suspended its program for weapons of mass destruction, but Saddam Hussein fostered ambiguity about the weapons in the minds of regional leaders to forestall any possible attacks against Iraq.

In 1998, a standoff between Hussein and the United Nations over weapons inspections led President Bill Clinton to launch punitive strikes aimed at debilitating what was thought to be a developed chemical weapons program. Attacks began on December 16, 1998. More than two hundred cruise missiles fired from U.S. Navy warships and Air Force B-52 bombers flew into Iraq, targeting suspected chemical weapons storage facilities, missile batteries, and command centers. Airstrikes continued for three more days, unleashing in total 415 cruise missiles and 600 bombs against 97 targets. The number of bombs dropped was nearly double the number used in the 1991 conflict.

The United States and Iraq remained at odds throughout the 1990s and early 2000, when Bush administration officials began championing “regime change.” The administration publicly denounced Saddam Hussein’s regime and its alleged weapons of mass destruction. Deceptively tying Saddam Hussein to international terrorists—a majority of Americans linked Hussein to the 9/11 attacks21 The administration’s push for war was in full swing. Protests broke out across the country and all over the world, but majorities of Americans supported military action. On October 16, Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq resolution, giving Bush the power to make war in Iraq. Iraq began cooperating with UN weapons inspectors in late 2002, but the Bush administration pressed on. On February 6, 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell, who had risen to public prominence as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of State during the Persian Gulf War in 1991, presented allegations of a robust Iraqi weapons program to the UN. Protests continued.

The first American bombs hit Baghdad on March 20, 2003. Several hundred thousand troops moved into Iraq and Hussein’s regime quickly collapsed. Baghdad fell on April 9. On May 1, 2003, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, beneath a banner reading Mission Accomplished, George W. Bush announced that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended.”22 No evidence of weapons of mass destruction were ever found. And combat operations had not ended, not really. The Iraqi insurgency had begun, and the United States would spend the next ten years struggling to contain it.

Despite George W. Bush’s ill-conceived photo op under a Mission Accomplished banner in May 2003, combat operations in Iraq continued for years. Wikimedia.

Efforts by various intelligence gathering agencies led to the capture of Saddam Hussein, hidden in an underground compartment near his hometown, on December 13, 2003. The new Iraqi government found him guilty of crimes against humanity and he was hanged on December 30, 2006. But the war in Iraq was not over.

IV. The End of the Bush Years

The War on Terror was a centerpiece in the race for the White House in 2004. The Democratic ticket, headed by Massachusetts senator John F. Kerry, a Vietnam War hero who entered the public consciousness for his subsequent testimony against it, attacked Bush for the ongoing inability to contain the Iraqi insurgency or to find weapons of mass destruction, the revelation and photographic evidence that American soldiers had abused prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison outside Baghdad, and the inability to find Osama bin Laden. Moreover, many enemy combatants who had been captured in Iraq and Afghanistan were “detained” indefinitely at a military prison in Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. “Gitmo” became infamous for its harsh treatment, indefinite detentions, and torture of prisoners. Bush defended the War on Terror, and his allies attacked critics for failing to “support the troops.” Moreover, Kerry had voted for the war—he had to attack the very thing that he had authorized. Bush won a close but clear victory.

The second Bush term saw the continued deterioration of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but Bush’s presidency would take a bigger hit from his perceived failure to respond to the domestic tragedy that followed Hurricane Katrina’s devastating hit on the Gulf Coast. Katrina had been a category 5 hurricane. It was, the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported, “the storm we always feared.”23

New Orleans suffered a direct hit, the levees broke, and the bulk of the city flooded. Thousands of refugees flocked to the Superdome, where supplies and medical treatment and evacuation were slow to come. Individuals died in the heat. Bodies wasted away. Americans saw poor Black Americans abandoned. Katrina became a symbol of a broken administrative system, a devastated coastline, and irreparable social structures that allowed escape and recovery for some and not for others. Critics charged that Bush had staffed his administration with incompetent supporters and had further ignored the displaced poor and Black residents of New Orleans.24

Hurricane Katrina was one of the deadliest and more destructive hurricanes to hit American soil in U.S. history. It nearly destroyed New Orleans, Louisiana, as well as cities, towns, and rural areas across the Gulf Coast. It sent hundreds of thousands of refugees to near-by cities like Houston, Texas, where they temporarily resided in massive structures like the Astrodome. Photograph, September 1, 2005. Wikimedia.

Immigration, meanwhile, had become an increasingly potent political issue. The Clinton administration had overseen the implementation of several anti-immigration policies on the U.S.-Mexico border, but hunger and poverty were stronger incentives than border enforcement policies were deterrents. Illegal immigration continued, often at great human cost, but nevertheless fanned widespread anti-immigration sentiment among many American conservatives. But George W. Bush used the issue to win re-election and Republicans used it in the 2006 mid-terms, passing legislation—with bipartisan support—that provided for a border “fence.” 700 miles of towering steel barriers sliced through border towns and deserts. Many immigrants and their supporters tried to fight back. The spring and summer of 2006 saw waves of protests across the country. Hundreds of thousands marched in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, and tens of thousands marched in smaller cities around the country. Legal change, however, went nowhere. Moderate conservatives feared upsetting business interests’ demand for cheap, exploitable labor and alienating large voting blocs by stifling immigration, and moderate liberals feared upsetting anti-immigrant groups by pushing too hard for liberalization of immigration laws. The fence was built and the border was tightened.

At the same time, Iraq descended further into chaos as insurgents battled against American troops and groups such as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s al-Qaeda in Iraq bombed civilians and released video recordings of beheadings. In 2007, twenty-seven thousand additional U.S. forces deployed to Iraq under the command of General David Petraeus. The effort, “the surge,” employed more sophisticated anti-insurgency strategies and, combined with Sunni efforts, pacified many of Iraq’s cities and provided cover for the withdrawal of American forces. On December 4, 2008, the Iraqi government approved the U.S.-Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, and U.S. combat forces withdrew from Iraqi cities before June 30, 2009. The last U.S. combat forces left Iraq on December 18, 2011. Violence and instability continued to rock the country.

Afghanistan, meanwhile, had also continued to deteriorate. In 2006, the Taliban reemerged, as the Afghan government proved both highly corrupt and incapable of providing social services or security for its citizens. The Taliban began re-acquiring territory. Money and American troops continued to prop up the Afghanistan government until American forces withdrew hastily in August 2021. The Taliban immediately took over the remainder of the country, outlasting America’s twenty-year occupation.

V. The Great Recession

The Great Recession began, as most American economic catastrophes began, with the bursting of a speculative bubble. Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium, home prices continued to climb, and financial services firms looked to cash in on what seemed to be a safe but lucrative investment. After the dot-com bubble burst, investors searched for a secure investment rooted in clear value, rather than in trendy technological speculation. What could be more secure than real estate? But mortgage companies began writing increasingly risky loans and then bundling them together and selling them over and over again, sometimes so quickly that it became difficult to determine exactly who owned what.

Decades of financial deregulation had rolled back Depression-era restraints and again allowed risky business practices to dominate the world of American finance. It was a bipartisan agenda. In the 1990s, for instance, Bill Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, repealing provisions of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act separating commercial and investment banks, and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which exempted credit-default swaps—perhaps the key financial mechanism behind the crash—from regulation.

Mortgages had been so heavily leveraged that when American homeowners began to default on their loans, the whole system collapsed. Major financial services firms such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers disappeared almost overnight. In order to prevent the crisis from spreading, President Bush signed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act and the federal government immediately began pouring billions of dollars into the industry, propping up hobbled banks. Massive giveaways to bankers created shock waves of resentment throughout the rest of the country, contributing to Obama’s 2008 election. But Obama oversaw the program after his inauguration. Thereafter, conservative members of the Tea Party decried the cronyism of an incoming Obama administration filled with former Wall Street executives. The same energies also motivated the Occupy Wall Street movement, as mostly young left-leaning New Yorkers protested an American economy that seemed overwhelmingly tilted toward “the one percent.”25

The Great Recession only magnified already rising income and wealth inequalities. According to the chief investment officer at JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States, “profit margins have reached levels not seen in decades,” and “reductions in wages and benefits explain the majority of the net improvement.”26 A study from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found that since the late 1970s, after-tax benefits of the wealthiest 1 percent grew by over 300 percent. The “average” American’s after-tax benefits had grown 35 percent. Economic trends have disproportionately and objectively benefited the wealthiest Americans. Still, despite political rhetoric, American frustration failed to generate anything like the social unrest of the early twentieth century. A weakened labor movement and a strong conservative bloc continue to stymie serious attempts at reversing or even slowing economic inequalities. Occupy Wall Street managed to generate a fair number of headlines and shift public discussion away from budget cuts and toward inequality, but its membership amounted to only a fraction of the far more influential and money-driven Tea Party. Its presence on the public stage was fleeting.

The Great Recession, however, was not. While American banks quickly recovered and recaptured their steady profits, and the American stock market climbed again to new heights, American workers continued to lag. Job growth was slow and unemployment rates would remain stubbornly high for years. Wages froze, meanwhile, and well-paying full-time jobs that were lost were too often replaced by low-paying, part-time work. A generation of workers coming of age within the crisis, moreover, had been savaged by the economic collapse. Unemployment among young Americans hovered for years at rates nearly double the national average.

VI. The Obama Years

In 2008, Barack Obama became the first African American elected to the presidency. In this official White House photo from May, 2009, 5-year-old Jacob Philadelphia said, “I want to know if my hair is just like yours.” The White House via Flickr.

By the 2008 election, with Iraq still in chaos, Democrats were ready to embrace the antiwar position and sought a candidate who had consistently opposed military action in Iraq. Senator Barack Obama had only been a member of the Illinois state senate when Congress debated the war actions, but he had publicly denounced the war, predicting the sectarian violence that would ensue, and remained critical of the invasion through his 2004 campaign for the U.S. Senate. He began running for president almost immediately after arriving in Washington.

A former law professor and community activist, Obama became the first African American candidate to ever capture the nomination of a major political party.27 During the election, Obama won the support of an increasingly antiwar electorate. When an already fragile economy finally collapsed in 2007 and 2008, Bush’s policies were widely blamed. Obama’s opponent, Republican senator John McCain, was tied to those policies and struggled to fight off the nation’s desire for a new political direction. Obama won a convincing victory in the fall and became the nation’s first African American president.

President Obama’s first term was marked by domestic affairs, especially his efforts to combat the Great Recession and to pass a national healthcare law. Obama came into office as the economy continued to deteriorate. He continued the bank bailout begun under his predecessor and launched a limited economic stimulus plan to provide government spending to reignite the economy.

Despite Obama’s dominant electoral victory, national politics fractured, and a conservative Republican firewall quickly arose against the Obama administration. The Tea Party became a catch-all term for a diffuse movement of fiercely conservative and politically frustrated American voters. Typically whiter, older, and richer than the average American, flush with support from wealthy backers, and clothed with the iconography of the Founding Fathers, Tea Party activists registered their deep suspicions of the federal government.28 Tea Party protests dominated the public eye in 2009 and activists steered the Republican Party far to the right, capturing primary elections all across the country.

Obama’s most substantive legislative achievement proved to be a national healthcare law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). Presidents since Theodore Roosevelt had striven to pass national healthcare reform and failed. Obama’s plan forsook liberal models of a national healthcare system and instead adopted a heretofore conservative model of subsidized private care (similar plans had been put forward by Republicans Richard Nixon, Newt Gingrich, and Obama’s 2012 opponent, Mitt Romney). Beset by conservative protests, Obama’s healthcare reform narrowly passed through Congress. It abolished pre-existing conditions as a cause for denying care, scrapped junk plans, provided for state-run healthcare exchanges (allowing individuals without healthcare to pool their purchasing power), offered states funds to subsidize an expansion of Medicaid, and required all Americans to provide proof of a health insurance plan that measured up to government-established standards (those who did not purchase a plan would pay a penalty tax, and those who could not afford insurance would be eligible for federal subsidies). The number of uninsured Americans remained stubbornly high, however, and conservatives spent most of the next decade attacking the bill.

Meanwhile, in 2009, President Barack Obama deployed seventeen thousand additional troops to Afghanistan as part of a counterinsurgency campaign that aimed to “disrupt, dismantle, and defeat” al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Meanwhile, U.S. Special Forces and CIA drones targeted al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders. In May 2011, U.S. Navy Sea, Air and Land Forces (SEALs) conducted a raid deep into Pakistan that led to the killing of Osama bin Laden. The United States and NATO began a phased withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2011, with an aim of removing all combat troops by 2014. Although weak militarily, the Taliban remained politically influential in south and eastern Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda remained active in Pakistan but shifted its bases to Yemen and the Horn of Africa. As of December 2013, the war in Afghanistan had claimed the lives of 3,397 U.S. service members.

Former Taliban fighters surrender their arms to the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan during a reintegration ceremony at the provincial governor’s compound in May 2012. Wikimedia.

VII. Stagnation

In 2012, Barack Obama won a second term by defeating Republican Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts. However, Obama’s inability to control Congress and the ascendancy of Tea Party Republicans stunted the passage of meaningful legislation. Obama was a lame duck before he ever won reelection, and gridlocked government came to represent an acute sense that much of American life—whether in politics, economics, or race relations—had grown stagnant.

The economy continued its halfhearted recovery from the Great Recession. The Obama administration campaigned on little to specifically address the crisis and, faced with congressional intransigence, accomplished even less. While corporate profits climbed and stock markets soared, wages stagnated and employment sagged for years after the Great Recession. By 2016, the statistically average American worker had not received a raise in almost forty years. The average worker in January 1973 earned $4.03 an hour. Adjusted for inflation, that wage was about two dollars per hour more than the average American earned in 2014. Working Americans were losing ground. Moreover, most income gains in the economy had been largely captured by a small number of wealthy earners. Between 2009 and 2013, 85 percent of all new income in the United States went to the top 1 percent of the population.29

But if money no longer flowed to American workers, it saturated American politics. In 2000, George W. Bush raised a record $172 million for his campaign. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first presidential candidate to decline public funds (removing any applicable caps to his total fund-raising) and raised nearly three quarters of a billion dollars for his campaign. The average House seat, meanwhile, cost about $1.6 million, and the average Senate Seat over $10 million.30 The Supreme Court, meanwhile, removed barriers to outside political spending. In 2002, Senators John McCain and Russ Feingold had crossed party lines to pass the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, bolstering campaign finance laws passed in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal in the 1970s. But political organizations—particularly PACs—exploited loopholes to raise large sums of money and, in 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. FEC that no limits could be placed on political spending by corporations, unions, and nonprofits. Money flowed even deeper into politics.

The influence of money in politics only heightened partisan gridlock, further blocking bipartisan progress on particular political issues. Climate change, for instance, has failed to transcend partisan barriers. In the 1970s and 1980s, experts substantiated the theory of anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming. Eventually, the most influential of these panels, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded in 1995 that there was a “discernible human influence on global climate.”31 This conclusion, though stated conservatively, was by that point essentially a scientific consensus. By 2007, the IPCC considered the evidence “unequivocal” and warned that “unmitigated climate change would, in the long term, be likely to exceed the capacity of natural, managed and human systems to adapt.”32

Climate change became a permanent and major topic of public discussion and policy in the twenty-first century. Fueled by popular coverage, most notably, perhaps, the documentary An Inconvenient Truth, based on Al Gore’s book and presentations of the same name, addressing climate change became a plank of the American left and a point of denial for the American right. American public opinion and political action still lagged far behind the scientific consensus on the dangers of global warming. Conservative politicians, conservative think tanks, and energy companies waged war to sow questions in the minds of Americans, who remain divided on the question, and so many others.

Much of the resistance to addressing climate change is economic. As Americans looked over their shoulder at China, many refused to sacrifice immediate economic growth for long-term environmental security. Twenty-first-century relations with China remained characterized by contradictions and interdependence. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, China reinvigorated its efforts to modernize its country. By liberating and subsidizing much of its economy and drawing enormous foreign investments, China has posted massive growth rates during the last several decades. Enormous cities rise by the day. In 2000, China had a GDP around an eighth the size of U.S. GDP. Based on growth rates and trends, analysts suggest that China’s economy will bypass that of the United States soon. American concerns about China’s political system have persisted, but money sometimes matters more to Americans. China has become one of the country’s leading trade partners. Cultural exchange has increased, and more and more Americans visit China each year, with many settling down to work and study.

VIII. American Carnage

By 2016, American voters were fed up. In that year’s presidential race, Republicans spurned their political establishment and nominated a real estate developer and celebrity billionaire, Donald Trump, who, decrying the tyranny of political correctness and promising to Make America Great Again, promised to build a wall to keep out Mexican immigrants and bar Muslim immigrants. The Democrats, meanwhile, flirted with the candidacy of Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist from Vermont, before ultimately nominating Hillary Clinton, who, after eight years as first lady in the 1990s, had served eight years in the Senate and four more as secretary of state. Voters despaired: Trump and Clinton were the most unpopular nominees in modern American history. Majorities of Americans viewed each candidate unfavorably and majorities in both parties said, early in the election season, that they were motivated more by voting against their rival candidate than for their own.33 With incomes frozen, politics gridlocked, race relations tense, and headlines full of violence, such frustrations only channeled a larger sense of stagnation, which upset traditional political allegiances. In the end, despite winning nearly three million more votes nationwide, Clinton failed to carry key Midwestern states where frustrated white, working-class voters abandoned the Democratic Party—a Republican president hadn’t carried Wisconsin, Michigan, or Pennsylvania, for instance, since the 1980s—and swung their support to the Republicans. Donald Trump won the presidency.

Donald Trump speaking at a 2018 rally. Photo by Gage Skidmore. Via Wikimedia.

Political divisions only deepened after the election. A nation already deeply split by income, culture, race, geography, and ideology continued to come apart. Trump’s presidency consumed national attention. Traditional print media and the consumers and producers of social media could not help but throw themselves at the ins and outs of Trump’s norm-smashing first years while seemingly refracting every major event through the prism of the Trump presidency. Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian election-meddling and the alleged collusion of campaign officials in that effort produced countless headlines.

New policies, meanwhile, enflamed widening cultural divisions. Border apprehensions and deportations reached record levels under the Obama administration, and Trump pushed even farther. He pushed for a massive wall along the border to supplement the fence built under the Bush administration. He began ordering the deportation of so-called Dreamers—students who were born elsewhere but grew up in the United States—and immigration officials separated refugee-status-seeking parents and children at the border. Trump’s border policies heartened his base and aggravated his opponents. While Trump enflamed America’s enduring culture war, his narrowly passed 2017 tax cut continued the redistribution of American wealth toward corporations and wealthy individuals. The tax cut grew the federal deficit and further exacerbated America’s widening economic inequality.

In his inaugural address, Donald Trump promised to end what he called “American carnage”—a nation ravaged, he said, by illegal immigrants, crime, and foreign economic competition. But, under his presidency, the nation only spiraled deeper into cultural and racial divisions, domestic unrest, and growing anxiety about the nation’s future. Trump represented an aggressive, pugilistic anti-liberalism, and, as president, never missing an opportunity to fuel on the fires of right-wing rage. Refusing to settle for the careful statement or defer to bureaucrats, Trump smashed many of the norms of the presidency and raged on his personal Twitter account. And he refused to be governed by the truth.

Few Americans, especially after the Johnson and Nixon administrations, believed that presidents never lied. But perhaps no president ever lied so boldly or so often as Donald Trump, who made, according to one accounting, an untrue statement every day for the first forty days of his presidency.34 By the latter years of his presidency, only about a third of Americans counted him as trustworthy.35 And that compulsive dishonesty led directly to January 6, 2021.

In November 2020, Joseph R. Biden, a longtime senator from Delaware and former Vice President under Barack Obama, running alongside Kamala Harris, a California senator who would become the nation’s first female vice president, convincingly defeated Donald Trump at the polls: Biden won the popular vote by a margin of four percent and the electoral vote by a margin of 74 votes, marking the first time an incumbent president had been defeated in over thirty years. But Trump refused to concede the election. He said it had been stolen. He said votes had been manufactured. He said it was all rigged. The claims were easily debunked, but it didn’t seem to matter: months after the election, somewhere between one-half and two-thirds of self-identified Republicans judged the election stolen.36 So when, on the afternoon of January 6, 2021, the president again articulated a litany of lies about the election and told the crowd of angry conspiracy-minded protestors to march to the Capitol and “fight like hell,” they did.

Thousands of Trump’s followers converged on the Capitol. Roughly one in seven of the more than 500 rioters later arrested were affiliated with extremist groups organized around conspiracy theories, white supremacy, and the right-wing militia movement.37 They waved American and Confederate flags, displayed conspiracy theory slogans and white supremacist icons, carried Christian iconography, and, above all, bore flags, hats, shirts, and other emblazoned with the name of Donald Trump.38 Arming themselves for hand-to-hand combat, they pushed past barriers and battled barricaded police officers. The Capitol attackers injured about 150 of them.39 Officers suffered concussions, burns, bruises, stab wounds, and broken bones.40 One suffered a non-fatal heart attack after being shocked repeatedly by a stun gun. Capitol Police Officer Brian D. Sicknick was killed, either by repeated attacks with a fire extinguisher or from mace or bear spray. Four other officers later died by suicide.

As the rioters breached the building, officers inside the House chamber moved furniture to barricade the doors as House members huddled together on the floor, waiting for a breach. Ashli Babbitt, a thirty-five-year-old Air Force veteran consumed by social-media conspiracy theories, and wearing a Trump flag around her neck, was shot and killed by a Capitol Police officer when she attempted to storm the chamber. The House Chamber held, but attackers breached the Senate Chamber on the opposite end of the building. Lawmakers had already been evacuated.

The rioters held the Capitol for several hours before the National Guard cleared it that evening. Congress, refusing to back down, stayed that evening to certify the results of the election. And yet, despite everything that had happened the day, the president’s unfounded claims of election fraud kept their grip on on Republican lawmakers. Eleven Republican senators and 150 of the House’s 212 Republicans lodged objections to the certification. And a little more than a month later, they refused to convict Donald Trump during his quickly organized second impeachment trial, this time for “incitement of insurrection.”

IX. The Pandemic

In the winter of 2019 and 2020, a new respiratory virus, Covid-19, emerged in Wuhan, China. It was a coronavirus, named after its spiky, crown-like appearance under a microscope. Other coronaviruses had been identified and contained in previous years, but, by December, Chinese doctors were treating dozens of cases, and, by January, hundreds. Wuhan shut down to contain the outbreak but the virus escaped. By January, the United States confirmed its first case. Deaths were reported in the Philippines and in France. Outbreaks struck Italy and Iran. And American case counts grew. Countries began locking down. Air travel slowed.

The virus was highly contagious and could be spread before the onset of symptoms. Many who had the virus were asymptomatic: they didn’t exhibit any symptoms at all. But others, especially the elderly and those with “co-morbidities,” were struck down. The virus attacked their airways, suffocating them. Doctors didn’t know what they were battling. They struggled to procure oxygen and respirators and incubated the worst cases with what they had. But the deaths piled up.

The virus hit New York City in the spring. The city was devastated. Hospitals overflowed as doctors struggled to treat a disease they barely understood. By April, thousands of patients were dying every day. The city couldn’t keep up with the bodies. Dozens of “mobile morgues” were set up to house bodies which wouldn’t be processed for months.41

With medical-grade masks in short supply, Americans made their own homemade cloth masks. Many right-wing Americans notably refused to wear them at all, further exposing workers and family members to the virus.

Failing to contain the outbreak, the country shut down. Flights stopped. Schools and restaurants closed. White-collar workers transitioned to working from home when offices shut down. But others weren’t so lucky. By April, 10 million Americans had lost their jobs.42

But shutdowns were scattered and incomplete. States were left to fend for themselves, setting their own policies and competing with one another to acquire scarce personal protective equipment (PPE). Many workers couldn’t stay home. Hourly workers, lacking paid sick leave, often had to choose between a paycheck and reporting to work having been exposed or even when presenting symptoms. Mask-wearing, meanwhile, was politicized. By May, 100,000 Americans were dead. A new wave of cases hit the South in July and August, overwhelming hospitals across much of the region. But the worst came in the winter, when the outbreak went fully national. Hundreds of thousands tested positive for the virus every day and nearly three-thousand Americans died every day throughout January and much of February.

The outbreak retreated in the spring, and pharmaceutical labs, flush with federal dollars, released new, cutting-edge vaccines. By late spring, Americans were getting vaccinated by the millions. The virus looked like it could be defeated. But many Americans, variously swayed by conspiracy theories peddled on social media or simply politically radicalized into associating vaccinations with anti-Trump politics, refused them. By late summer, barely a majority of those eligible for vaccines were fully vaccinated. More contagious and elusive strains evolved and spread and the virus continued churning through the population, sending many, especially the elderly, chronically ill, and unvaccinated, to hospitals and to early deaths. By the end of the summer of 2021, according to official counts, over 600,000 Americans had died from Covid-19. By May 2022, the official death toll in the United States crossed one million.

X. New Horizons

Americans looked anxiously to the future, and yet also, often, to a new generation busy discovering, perhaps, that change was not impossible. Much public commentary in the early twenty-first century concerned “Millennials” and “Generation Z,” the generations that came of age during the new millennium. Commentators, demographers, and political prognosticators continued to ask what the new generation will bring. Time’s May 20, 2013, cover, for instance, read Millennials Are Lazy, Entitled Narcissists Who Still Live with Their Parents: Why They’ll Save Us All. Pollsters focused on features that distinguish millennials from older Americans: millennials, the pollsters said, were more diverse, more liberal, less religious, and wracked by economic insecurity. “They are,” as one Pew report read, “relatively unattached to organized politics and religion, linked by social media, burdened by debt, distrustful of people, in no rush to marry—and optimistic about the future.”43

Millennial attitudes toward homosexuality and gay marriage reflected one of the most dramatic changes in the popular attitudes of recent years. After decades of advocacy, American attitudes shifted rapidly. In 2006, a majority of Americans still told Gallup pollsters that “gay or lesbian relations” was “morally wrong.”44 But prejudice against homosexuality plummeted and greater public acceptance of coming out opened the culture–in 2001, 73 percent of Americans said they knew someone who was gay, lesbian, or bisexual; in 1983, only 24 percent did. Gay characters—and in particular, gay characters with depth and complexity—could be found across the cultural landscape. Attitudes shifted such that, by the 2010s, polls registered majority support for the legalization of gay marriage. A writer for the Wall Street Journal called it “one of the fastest-moving changes in social attitudes of this generation.”45

Such change was, in many respects, a generational one: on average, younger Americans supported gay marriage in higher numbers than older Americans. The Obama administration, meanwhile, moved tentatively. Refusing to push for national interventions on the gay marriage front, Obama did, however, direct a review of Defense Department policies that repealed the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy in 2011. Without the support of national politicians, gay marriage was left to the courts. Beginning in Massachusetts in 2003, state courts had begun slowly ruling against gay marriage bans. Then, in June 2015, the Supreme Court ruled 5–4 in Obergefell v. Hodges that same-sex marriage was a constitutional right. Nearly two thirds of Americans supported the position.46

While liberal social attitudes marked the younger generation, perhaps nothing defined young Americans more than the embrace of technology. The Internet in particular, liberated from desktop modems, shaped more of daily life than ever before. The release of the Apple iPhone in 2007 popularized the concept of smartphones for millions of consumers and, by 2011, about a third of Americans owned a mobile computing device. Four years later, two thirds did.47.

Together with the advent of social media, Americans used their smartphones and their desktops to stay in touch with old acquaintances, chat with friends, share photos, and interpret the world—as newspaper and magazine subscriptions dwindled, Americans increasingly turned to their social media networks for news and information.48 Ambitious new online media companies, hungry for clicks and the ad revenue they represented, churned out provocatively titled, easy-to-digest stories that could be linked and tweeted and shared widely among like-minded online communities,49 but even traditional media companies, forced to downsize their newsrooms to accommodate shrinking revenues, fought to adapt to their new online consumers.

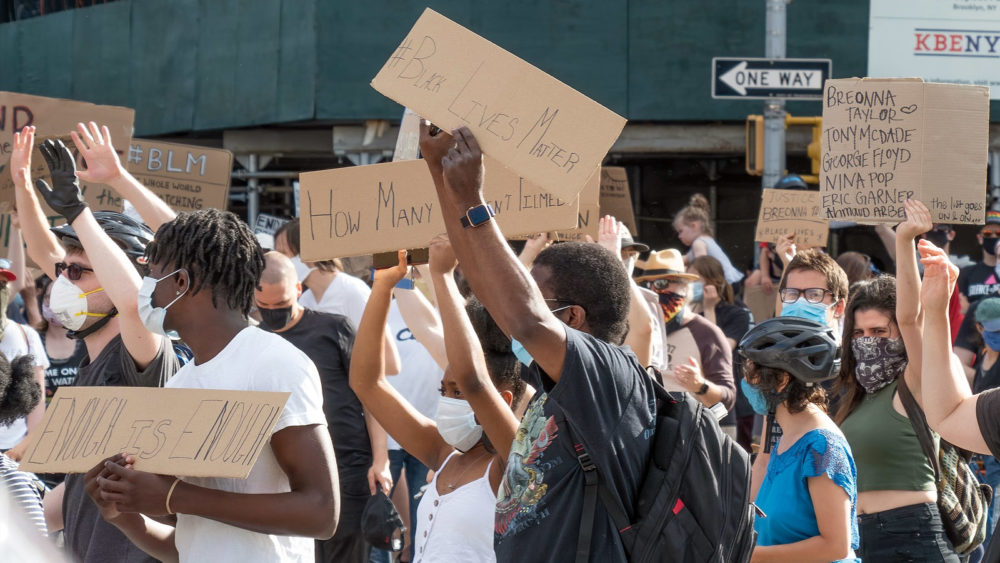

The ability of individuals to share stories through social media apps revolutionized the media landscape—smartphone technology and the democratization of media reshaped political debates and introduced new political questions. The easy accessibility of video capturing and the ability for stories to go viral outside traditional media, for instance, brought new attention to the tense and often violent relations between municipal police officers and African Americans. The 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, sparked protests and focused the issue. It perhaps became a testament to the power of social media platforms such as Twitter that a hashtag, #blacklivesmatter, became a rallying cry for protesters and counterhashtags, #alllivesmatter and #bluelivesmatter, for critics.50 But a relentless number of videos documenting the deaths of Black men at the hands of police officers continued to circulated across social media networks. The deaths of Eric Garner, twelve-year-old Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, and were captured on cell phone cameras and went viral. So too did the stories of Breonna Taylor and Botham Jean. “Say their names,” a popular chant at Black Lives Matters marches went. And then George Floyd was murdered.

George Floyd’s murder in 2020 sparked the largest protests in American history. Here, crowds holding homemade signs protest in New York City. Via Wikimedia.

On May 25, 2020, a teenager, Darnella Frazier, filmed Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin with his knee on the neck of George Floyd. “I can’t breathe,” Floyd said. Despite his pleas, and those of bystanders, Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes. Floyd’s body had long gone limp. The horrific footage shocked much of the country. Despite state and local lockdowns to slow the spread of Covid-19, spontaneous demonstrations broke out across the country. Protests erupted not only in major cities but in small towns and rural communities. The demonstrations dwarfed, in raw numbers, any comparable protest in American history. Taken together, as many as 25-million Americans may have participated in racial justice demonstrations that summer.51 And yet, despite the marches, no great national policy changes quickly followed. The “system” resisted calls to address “systemic racism.” Localities made efforts, of course. Criminal justice reformers won elections as district attorneys. Police departments mandated their officers carry body cameras. As cries of “defund the police” sounded among left-wing Americans, some cities experimented with alternative emergency services that emphasized mediation and mental health. Meanwhile, at a symbolic level, Democratic-leaning towns and cities in the South pulled down their Confederate iconography. But the intractable racial injustices embedded deeply within American life had not been uprooted and racial disparities in wealth, education, health, and other measures persevered, as they already had, in the United States, for hundreds of years.

As the Black Lives Matter movement captured national attention, another social media phenomenon, the #MeToo movement, began as the magnification of and outrage toward the past sexual crimes of notable male celebrities before injecting a greater intolerance toward those accused of sexual harassment and violence into much of the rest of American society. The sudden zero tolerance reflected the new political energies of many American women, sparked in large part by the candidacy and presidency of Donald Trump. The day after Trump’s inauguration, between five hundred thousand and one million people descended on Washington, D.C., for the Women’s March, and millions more demonstrated in cities and towns around the country to show a broadly defined commitment toward the rights of women and others in the face of the Trump presidency. And with three appointments to the Supreme Court, Donald Trump’s legacy persisted past his presidency. On June 24, 2022, the new conservative majority decided Dobbs v. Jackson, overturning Roe v. Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), cases that established a constitutional right to abortion. Meanwhile, other avenues of sexual politics opened across the country. By the 2020s, the broader American culture increasingly featured transgender individuals in media and many Americans began making their preferred pronouns explicit–as well as deploying “they” as a gender-neutral pronoun–to undermine fixed notions of gender. Many conservatives, however, fought back. State legislators around the country sponsored “bathroom bills” to keep transgender individuals out of the bathroom of their identified gender, alleging that they posed a violent sexual risk. In Texas, Attorney General Ken Paxton declared pediatric gender-affirming care to be child abuse.

As issues of race and gender captured much public discussion, immigration continued on as a potent political issue. Even as anti-immigrant initiatives like California’s Proposition 187 (1994) and Arizona’s SB1070 (2010) reflected the anxieties of many white Americans, younger Americans proved far more comfortable with immigration and diversity (which makes sense, given that they are the most diverse American generation in living memory). Since Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society liberalized immigration laws in the 1960s, the demographics of the United States have been transformed. In 2012, nearly one quarter of all Americans were immigrants or the sons and daughters of immigrants. Half came from Latin America. The ongoing Hispanicization of the United States and the ever-shrinking proportion of non-Hispanic whites have been the most talked about trends among demographic observers. By 2013, 17 percent of the nation was Hispanic. In 2014, Latinos surpassed non-Latino whites to become the largest ethnic group in California. In Texas, the image of a white cowboy hardly captures the demographics of a minority-majority state in which Hispanic Texans will soon become the largest ethnic group. For the nearly 1.5 million people of Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, for instance, where most residents speak Spanish at home, a full three fourths of the population is bilingual.52 Political commentators often wonder what political transformations these populations will bring about when they come of age and begin voting in larger numbers.

IX. Conclusion

The collapse of the Soviet Union brought neither global peace nor stability, and the attacks of September 11, 2001, plunged the United States into interminable conflicts around the world. At home, economic recession, a slow recovery, stagnant wage growth, and general pessimism infected American life as contentious politics and cultural divisions poisoned social harmony, leading directly to the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol. And yet the stream of history changes its course. Trends shift, things change, and events turn. New generations bring with them new perspectives, and they share new ideas. Our world is not foreordained. It is the product of history, the ever-evolving culmination of a longer and broader story, of a larger history, of a raw, distinctive, American Yawp.

X. Primary Sources

1. Bill Clinton on Free Trade and Financial Deregulation (1993-2000)

During his time in office, Bill Clinton passed the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) in 1993, allowing for the free movement of goods between Mexico, the United States, and Canada, signed legislation repealing the Glass-Steagall Act, a major plank of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal banking regulation, and deregulated the trading of derivatives, including credit default swaps, a complicated financial instrument that would play a key role in the 2007-2008 economic crash. In the following signing statements, Clinton offers his support of free trade and deregulation.

2. 9/11 Commission Report, “Reflecting On A Generational Challenge” (2004)

On July 22, 2004, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States—or, the 9/11 Commission—delivered a 500-plus-page report that investigated the origins of the 9/11 attacks and America’s response and offered policy prescriptions for a post-9/11 world.

3. George W. Bush on the Post-9/11 World (2002)

In his 2002 State of the Union Address, George W. Bush proclaimed that the attacks of September 11 signaled a new, dangerous world that demanded American interventions. Bush identified an “Axis of Evil” and provided a justification for a broad “war on terror.”

4. Obergefell v. Hodges (2015)

In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that prohibitions against same-sex marriage were unconstitutional. Gay marriage had been a divisive issue in American politics for well over a decade. Many states passed referendums and constitutional amendments barring same-sex marriages and, in 1996, Bill Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act, defining marriage at the federal level as between a man and a woman. In 2003, the Massachusetts Supreme Court struck down Massachusetts’ state’s prohibition, making it the first state to legally marry same-sex couples. More followed and public opinion began to turn. Although President Obama still refused to support it, by 2011 a majority of Americans believed same-sex marriages should be legally recognized. Four years later, the Supreme Court issued its Obergefell decision. The majority opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, considered the relationship between history and shifting notions of liberty and injustice.

5. Pedro Lopez on His Mother’s Deportation (2008/2015)

Pedro Lopez immigrated to Postville, Iowa, with his family as a young child. On May 12, 2008, Pedro Lopez’s mother, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, was arrested, jailed, and deported to Mexico. Pedro was 13. Here, he describes the experience.

6. Chelsea Manning Petitions for a Pardon (2013)

Chelsea Manning, a U.S. Army intelligence analyst, was convicted in 2013 for violating the Espionage Act by leaking classified documents revealing the killing of civilians, the torture of prisoners, and other nefarious actions committed by the United States in the War on Terror. After being sentenced to thirty-five years in federal prison, she delivered a statement, through her attorney, explaining her actions and requesting a pardon from President Barack Obama. Manning’s sentence was commuted in 2017.

7. Emily Doe, Victim Impact Statement (2015)

On January 18, 2015, Stanford University student Brock Turner sexually assaulted an unconscious woman outside of a university fraternity house. At his sentencing on June 2, 2016, his unnamed victim (“Emily Doe”) read a 7,000-word victim impact statement describing the effect of the assault on her life. [Note: Chanel Miller identified herself publicly as Emily Doe in September 2019.]

A worker stands in front of rubble from the World Trade Center at Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan several weeks after the September 11 attacks.

9. Barack Obama and a Young Boy (2009)

In 2008, Barack Obama became the first African American elected to the presidency. In this official White House photo from May, 2009, 5-year-old Jacob Philadelphia said, “I want to know if my hair is just like yours.”

XI. Reference Material

This chapter was edited by Michael Hammond, with content contributions by Eladio Bobadilla, Andrew Chadwick, Zach Fredman, Leif Fredrickson, Michael Hammond, Richara Hayward, Joseph Locke, Mark Kukis, Shaul Mitelpunkt, Michelle Reeves, Elizabeth Skilton, Bill Speer, and Ben Wright.

Recommended citation: Eladio Bobadilla et al., “The Recent Past,” Michael Hammond, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press, 2012.

- Canaday, Margot. The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1996.

- Cowie, Jefferson. Capital Moves: RCA’s 70-Year Quest for Cheap Labor. New York: New Press, 2001.

- Ehrenreich, Barbara. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. New York: Metropolitan, 2001.

- Evans, Sara. Tidal Wave: How Women Changed America at Century’s End. New York: Free Press, 2003.

- Gardner, Lloyd C. The Long Road to Baghdad: A History of U.S. Foreign Policy from the 1970s to the Present. New York: Free Press, 2008.

- Hinton, Elizabeth. From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Hollinger, David. Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

- Hunter, James D. Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

- Meyerowitz, Joanne. How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Mittelstadt, Jennifer. The Rise of the Military Welfare State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Moreton, Bethany. To Serve God and Walmart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Nadasen, Premilla. Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Osnos, Evan. Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Faith in the New China. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

- Packer, George. The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

- Patterson, James T. Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Translated from the French by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2013.

- Ricks, Thomas E. Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. New York: Penguin, 2006.

- Schlosser, Eric. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. New York: Norton, 2010.

- Taylor, Paul. The Next America: Boomers, Millennials, and the Looming Generational Showdown. New York: Public Affairs, 2014.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

- Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Wright, Lawrence. The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf, 2006.

Notes

- https://apnews.com/article/ap-fact-check-donald-trump-capitol-siege-violence-elections-507f4febbadecb84e1637e55999ac0ea. [↩]

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2021/01/14/dc-police-capitol-riot/. [↩]

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/27/us/jan-6-inquiry.html. [↩]

- William Faulker, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Random House, 1954), 73. [↩]

- Bill Minutaglio, First Son: George W. Bush and the Bush Family Dynasty (New York: Random House, 1999), 210–224. [↩]

- Roger Simon, “How a Murderer and Rapist Became the Bush Campaign’s Most Valuable Player,” Baltimore Sun, November 11, 1990. [↩]

- See especially Dan T. Carter, From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994 (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1996), 72–80. [↩]

- Sean Wilentz, The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008 (New York: HarperCollins, 2008). [↩]

- James F. Clarity, “End of the Soviet Union,” New York Times, December 26, 1991. [↩]

- Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest (Summer 1989). [↩]

- William Thomas Allison, The Gulf War, 1990–91 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 145, 165. [↩]

- Charles W. Dunn, The Presidency in the Twenty-first Century (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011), 152. [↩]

- Robert M. Collins, Transforming America: Politics and Culture During the Reagan Years (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 171, 172. [↩]

- For Clinton’s presidency and the broader politics of the 1990s, see James T. Patterson, Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Wilentz, Age of Reagan. [↩]

- Patterson, Restless Giant, 298–299. [↩]