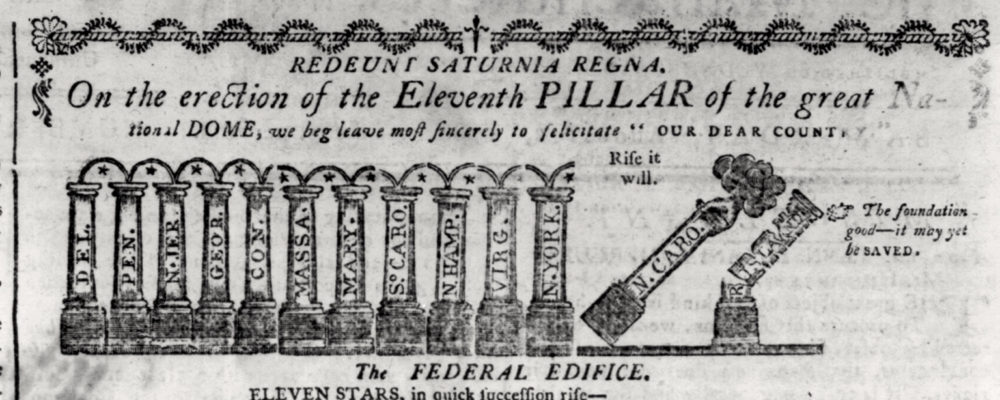

“The Federal Pillars,” from The Massachusetts Centinel, August 2, 1789, via Library of Congress.

Introduction

A grand debate over political power engulfed the young United States. The Constitution ensured that there would be a strong federal government capable of taxing, waging war, and making law, but it could never resolve the young nation’s many conflicting constituencies. The new nation was never as cohesive as its champions had hoped. Although the officials of the new federal government—and the people who supported it—placed great emphasis on unity and cooperation, the country was often anything but unified. As the 1790s progressed, Americans became bitterly divided over political parties and foreign wars. As party differences and regional quarrels tested the federal government, the new nation increasingly explored the limits of its democracy. Analyzing these sources allows us to see these national tensions and the limits to American democracy.

Documents

Hector St. John de Crèvecœur was born in France, but relocated to the colony of New York and married a local woman named Mehitable Tippet. For a period of several years, de Crèvecœur wrote about the people he encountered in North America. The resulting work was widely successful in Europe. In this passage, Crèvecœur attempts to reflect on the difference between life in Europe and life in North America.

In 1786, half a year before the Constitutional Convention, a collection of Native American leaders gathered on the banks of the Detroit River to offer a unified message to the Congress of the United States. Despite this proposal, American surveyors, settlers, and others continued to cross the Ohio River.

In the aftermath of the Revolution, politics became a sport consumed by both men and women. In a series of letters sent to her sister, Mary Smith Cranch comments on a series of political events including the lack of support for diplomats, the circulation of paper or hard currency, legal reform, tariffs against imported tea tables, Shays rebellion, and the role of women in supporting the nation’s interests.

Before the American Revolution, Virginia supported local Anglican churches through taxes. After the American Revolution, Virginia had to decide what to do with this policy. Some founding fathers, including Patrick Henry, wanted to equally distribute tax dollars to all churches. In this document, James Madison explains why he did not want any government money to support religious causes in Virginia.

George Washington used his final public address as president to warn against what he understood as the two greatest dangers to American prosperity: political parties and foreign wars. Washington urged the American people to avoid political partisanship and entanglements with European wars.

Venture Smith’s autobiography is one of the earliest slave narratives to circulate in the Atlantic World. Slave narratives grew into the most important genre of antislavery literature and bore testimony to the injustices of the slave system. Smith was unusually lucky in that he was able to purchase his freedom, but his story nonetheless reveals the hardships faced by even the most fortunate enslaved men and women.

In Charlotte Temple, the first novel written in America, Susannah Rowson offered a cautionary tale of a woman deceived and then abandoned by a roguish man. Americans throughout the new nation read the book with rapt attention and many even traveled to New York City to visit the supposed grave of this fictional character.

Media

“The Federal Pillars,” from The Massachusetts Centinel, August 2, 1789, via Library of Congress.

The Massachusetts Centinel ran a series of cartoons depicting the ratification of the Constitution. Each vertical pillar represents a state that has ratified the new government. In this cartoon, North Carolina’s pillar is being guided into place (it would vote for ratification in November 1789). Rhode Island’s pillar, however, is crumbling and shows the uncertainty of the vote there.

This image attacks Jefferson’s support of the French Revolution and religious freedom. The letter, “To Mazzei,” refers to a 1796 correspondence that criticized the Federalists and, by association, President Washington. Providential Detection, 1797. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society. Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

“Providential Detection,” 1797 via American Antiquarian Society.

This image attacks Jefferson’s support of the French Revolution and religious freedom. The Altar to “Gallic Despotism” mocks Jefferson’s allegiance to the French. The letter, “To Mazzei,” refers to a 1796 correspondence that criticized the Federalists and, by association, President Washington.