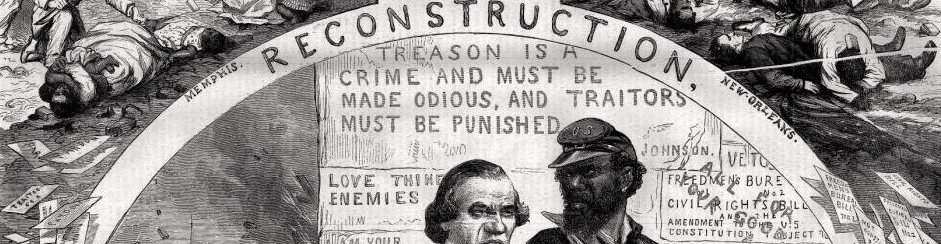

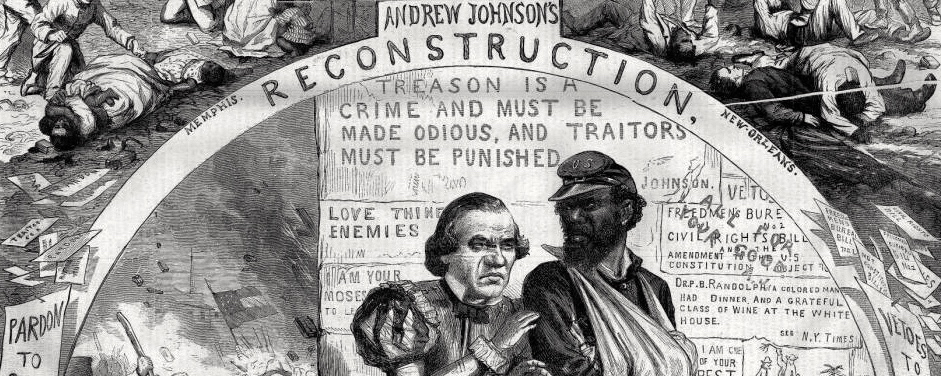

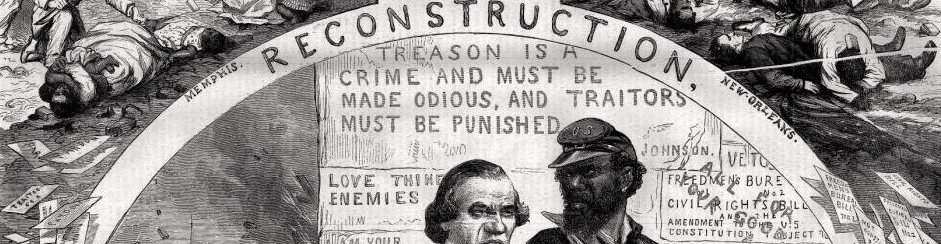

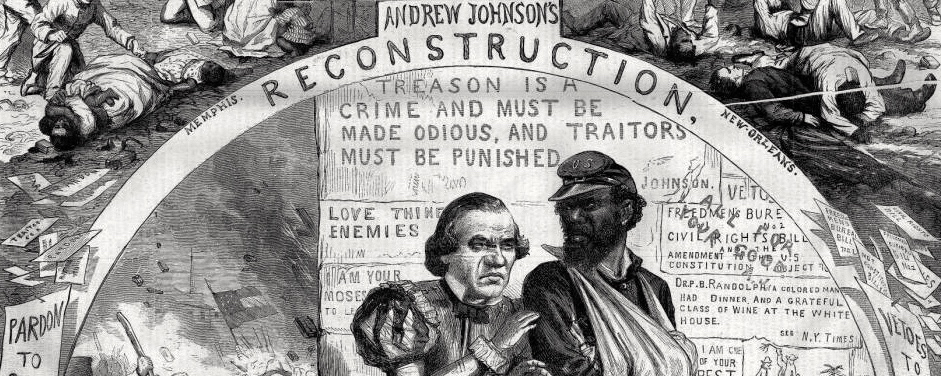

Thomas Nast, “Reconstruction and How It Works,” Harper’s Weekly, 1866, via HarpWeek.

Introduction

After the Civil War, much of the South lay in ruins. How would these states be brought back into the Union? Would they be conquered territories or equal states? How would they rebuild their governments, economies, and social systems? What rights did freedom confer upon formerly enslaved people? The answers to many of Reconstruction’s questions hinged upon the concepts of citizenship and equality. The era witnessed perhaps the most open and widespread discussions of citizenship since the nation’s founding. It was a moment of revolutionary possibility and violent backlash. African Americans and Radical Republicans pushed the nation to finally realize the Declaration of Independence’s promises that “all men were created equal” and had “certain, unalienable rights.” Conservative white Democrats granted African Americans legal freedom but little more. When black Americans and their radical allies succeeded in securing citizenship for freedpeople, a new fight commenced to determine the legal, political, and social implications of American citizenship. Resistance continued, and Reconstruction eventually collapsed. In the South, limits on human freedom endured and would stand for nearly a century more. These sources gesture toward both the successes and failures of Reconstruction.

Documents

Charlotte Forten was born into a wealthy black family in Philadelphia. After receiving an education in Salem, Massachusetts, Forten became the first black American hired to teach white students. She lent her educational expertise to the war effort by relocating to South Carolina in 1862 with the goal of educating former slaves. This excerpt from her diary explains her experiences during this time.

Black Americans hoped that the end of the Civil War would create an entirely new world, while white southerners tried to restore the antebellum order as much as they could. Most slave-owners sought to maintain control over their former slaves through sharecropping contracts. P.H. Anderson of Tennessee was one such former slave-owner. After the war, he contacted his former slave Jourdon Anderson, offering him a job opportunity. The following is Jourdon Anderson’s reply.

Many southern governments enacted legislation that reestablished antebellum power relationships. South Carolina and Mississippi passed laws known as Black Codes to regulate black behavior and impose social and economic control. While they granted some rights to African Americans – like the right to own property, to marry or to make contracts – they also denied other fundamental rights. Mississippi’s vagrant law, excerpted here, required all freedmen to carry papers proving they had means of employment. If they had no proof, they could be arrested, fined, or even re-enslaved and leased out to their former master.

Most histories of the Civil War claim that the war ended in the summer of 1865 when Confederate armies surrendered. However, violent resistance and terrorism continued in the South for over a decade. In this report, General J.J. Reynolds describes the lawlessness of Texas during Reconstruction.

Americans came together after the Civil War largely by collectively forgetting what the war was about. Celebrations honored the bravery of both armies, and the meaning of the war faded. Frederick Douglass and other black leaders engaged with Confederate sympathizers in a battle of historical memory. In this speech, Douglass calls on Americans to remember the war for what it was—a struggle between an army fighting to protect slavery and a nation reluctantly transformed into a force for liberation.

Media

Thomas Nast, “Reconstruction and How It Works,” Harper’s Weekly, 1866, via HarpWeek.

This print mocks Reconstruction by making several allusions to Shakespeare. The center illustration shows a black soldier as Othello and President Andrew Johnson as Iago. Johnson’s slogans “Treason is a crime and must be made odious” and “I am your Moses” are on the wall. The top left shows a riot in Memphis and at the top a riot in New Orleans. At the bottom, Johnson is trying to charm a Confederate Copperhead. General Benjamin Butler is at the bottom left, accepting the Confederate surrender of New Orleans in 1862. This scene is contrasted to the bottom right where General Philips Sheridan bows to Louisiana Attorney General Andrew Herron in 1866, implying a defeat for Reconstruction. Click on the image for more information.

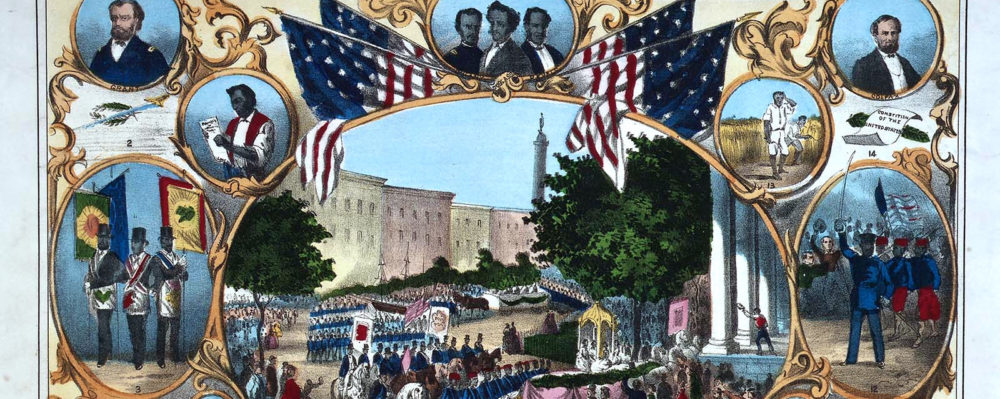

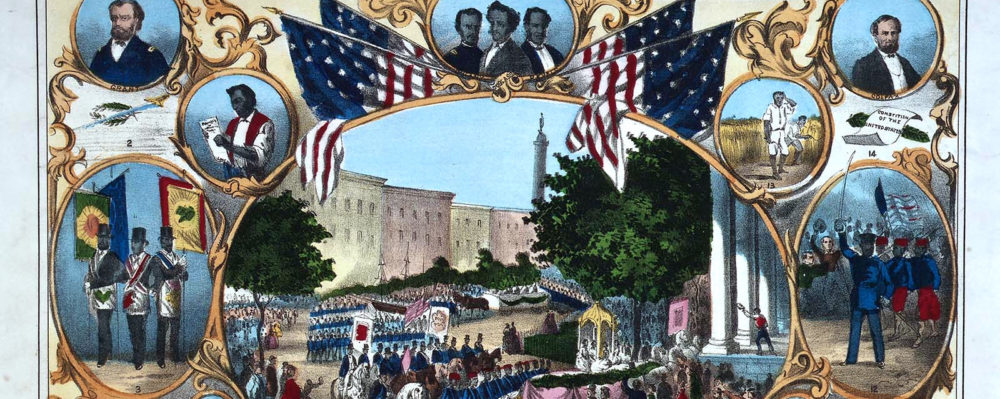

Thomas Kelley, “The Fifteenth Amendment,” 1870, via Wikimedia.

This 1870 print celebrated the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. Here we see several of the themes most important to black Americans during Reconstruction: The print celebrates the military achievements of black veterans, the voting rights protected by the amendment, the right to marry and establish families, the creation and protection of black churches, and the right to own and improve land. Unfortunately, many of these freedoms would be short-lived as the United States retreated from Reconstruction.