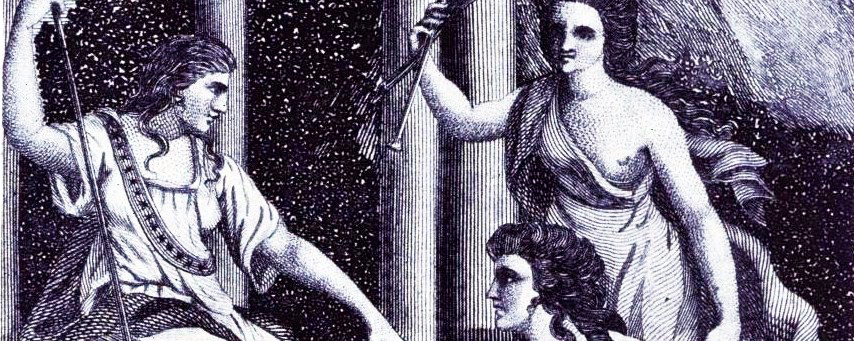

John J. Bartlett, “America guided by wisdom An allegorical representation of the United States depicting their independence and prosperity,” 1815, via Library of Congress.

Introduction

Thomas Jefferson’s electoral victory over John Adams—and the larger victory of the Republicans over the Federalists—was but one of many changes in the early republic. The wealthy and the powerful, middling and poor whites, Native Americans, free and enslaved African Americans, influential and poor women: all demanded a voice in the new nation that Thomas Paine called an “asylum” for liberty. They would all, in their own way, lay claim to the ideals of freedom and equality heralded, if not fully realized, by the Revolution. These sources show these competing claims to freedom and reveal the competing visions for the new nation.

Documents

The elimination of slavery in northern states like Pennsylvania was slow and hard-fought. A bill passed in 1780 began the slow process of eroding slavery in the state, but a proposal just one year later would have erased that bill and furthered the distance between slavery and freedom. The action of Black Philadelphians and others succeeded in defeating this measure. In this letter to the Black newspaper, Philadelphia Freedom’s Journal, a formerly enslaved man uses the rhetoric of the American Revolution to attack American slavery.

American racism spread during the first decades after the American Revolution. Racial prejudice existed for centuries, but the belief that African-descended peoples were inherently and permanently inferior to Anglo-descended peoples developed sometime around the late eighteenth century. Writings such as this piece from Thomas Jefferson fostered faulty scientific reasoning to justify laws that protected slavery and white supremacy.

Benjamin Banneker, a free Black American and largely self-taught astronomer and mathematician, wrote Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, on August 19, 1791. Banneker included this letter, as well as Jefferson’s short reply, in several of the first editions of his almanacs in part because he hoped it would dispel the widespread assumption that Jefferson perpetuated in his Notes on the State of Virginia that Black people were incapable of intellectual achievement.

Native peoples had long employed strategies of playing Europeans off against each other to maintain their independence and neutrality. As early as 1785, the Creek headman Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko) saw the threat the expansionist Americans placed on Native peoples and the inability of a weak United States government to restrain their citizens from encroaching on Native lands. McGillivray sought the aid and protection of the Spanish in order to maintain the supply of trade goods into Creek country and counter the Americans.

Like Pontiac before him, Tecumseh articulated a spiritual message of Native American unity and resistance. In this document, he acknowledges his Shawnee heritage, but appeals to a larger community of “red men,” who he describes as “once a happy race, since made miserable by the white people.” This document reveals not only Tecumseh’s message of resistance, but it also shows that Anglo-American understandings of race had spread to Native Americans as well.

Americans were not united in their support for the War of 1812. In these two documents we hear from members of congress as they debate whether or not America should go to war against Great Britain.

Women in early America suffered from a lack of rights or means of defending themselves against domestic abuse. The case of Abigail Bailey is remarkable because she was able to successfully free herself and her children from an abusive husband and father.

Media

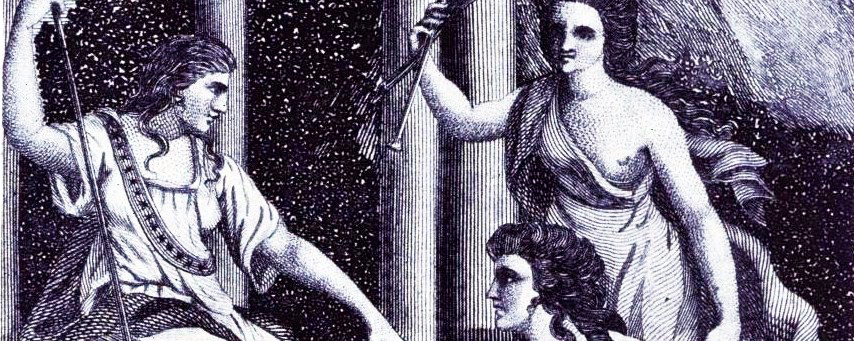

Thackara & Vallance, Frontispiece and title page from “The Lady’s magazine, and repository of entertaining knowledge” showing the “Genius of the Ladies magazine” presenting the figure of Liberty with a copy of Mary Wollstoncraft’s “Vindication of the rights of women,” 1792 via Library of Congress.

Despite the restrictions imposed on their American citizenship, white women worked to expand their rights to education in the new nation using literature and the arts. The first journal for women in the United States, The Lady’s Magazine, and repository of entertaining knowledge, introduced their initial volume with an engraving celebrating the transatlantic exchange between women’s rights advocates. In the engraving, English writer Mary Wollstonecraft presents her work, “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman,” to Liberty who has the tools of the arts at her feet.

John J. Bartlett, “America guided by wisdom An allegorical representation of the United States depicting their independence and prosperity,” 1815, via Library of Congress.

This engraving reflects the sense of triumph many white Americans felt following the War of 1812. Drawing from the visual language of Jeffersonian Republicans, we see America—represented as a woman in classical dress—surrounded by gods of wisdom, commerce, and agriculture on one side and a statue of George Washington emblazoned with the recent war’s victories on the other. The romantic sense of the United States as the heir to the ancient Roman republic, pride in military victory, and the glorification of domestic production contributed to the idea the young nation was about to enter an “era of good feelings.”