Andreas F. Borchert, “Mesa Verde National Park Cliff Palace” via Wikimedia.

Introduction

Europeans called the Americas “The New World.” But for the millions of Native Americans they encountered, it was anything but. Human beings have lived here for over ten millennia. American history begins with them, the first Americans. But where does their story begin? Native Americans passed stories through the millennia that tell of their creation and values. The arrival of Europeans and resulting Columbian Exchange united two worlds and ten-thousand years of history. Both sides of the world transformed. And neither would ever again be the same. These sources explore the contours of Native American life and the conflicts that resulted from the arrival of Europeans.

Documents

These two Native American creation stories are among thousands of accounts for the origins of the world. The Salinian and Cherokee, from what we now call California and the American southeast respectively, both exhibit the common Native American tendency to locate spiritual power in the natural world. For both Native Americans and Europeans, the collision of two continents challenged old ideas and created new ones as well.

First encounters between Europeans and Native Americans were dramatic events. In this account we see the assumptions and intentions of Christopher Columbus, as he immediately began assessing the potential of these people to serve European economic interests. He also predicted easy success for missionaries seeking to convert these people to Christianity.

This source aggregates a number of early written reports by Aztec authors describing the destruction of Tenochtitlan at the hands of a coalition of Spanish and Indigenous armies. This collection of sources was assembled by Miguel Leon Portilla, a Mexican anthropologist.

Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Spanish Dominican priest, wrote directly to the King of Spain hoping for new laws to prevent the brutal exploitation of Native Americans. Las Casas’s writings quickly spread around Europe and were used as humanitarian justification for other European nations to challenge Spain’s colonial empire with their own schemes of conquest and colonization.

Thomas Morton both admired and condemned aspects of Native American culture. In his descriptions, we can find not only information about the people he is describing but also a window into the concerns of Englishmen like Morton who could use descriptions of Native Americans as a means of criticizing English culture.

Cuauhtlatoatzin was one of the first Aztec men to convert to Christianity after the Spanish invasion. Renamed as Juan Diego, he soon thereafter reported an appearance of the Virgin Mary called the Virgin of Guadalupe. This apparition became an important symbol for a new native Christianity. These excerpts are translated from an account first published in Nahuatl by Luis Lasso de la Vega in 1649.

Spanish explorer, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, traveled across the Gulf South, from Florida to Mexico. As he traveled, Cabeza de Vaca developed a reputation as a faith healer. In his account he claimed several instances of performing miracles, illustrating his spiritual beliefs as well as offering a rare, if perhaps unreliable, glimpse at the life of Native Americans in the area.

Media

Andreas F. Borchert, “Mesa Verde National Park Cliff Palace” via Wikimedia.

Native peoples in the Southwest began constructing these highly defensible cliff dwellings in 1190 CE and continued expanding and refurbishing them until 1260 CE before abandoning them around 1300 CE. Changing climatic conditions resulted in an increased competition for resources that led some groups to ally with their neighbors for both protection and subsistence. The circular rooms in the foreground were called kivas and had ceremonial and religious importance for the inhabitants. Cliff Palace had 23 kivas and 150 rooms housing a population of approximately 100 people; the number of rooms and large population has led scholars to believe that this complex may have been the center of a larger polity that included surrounding communities.

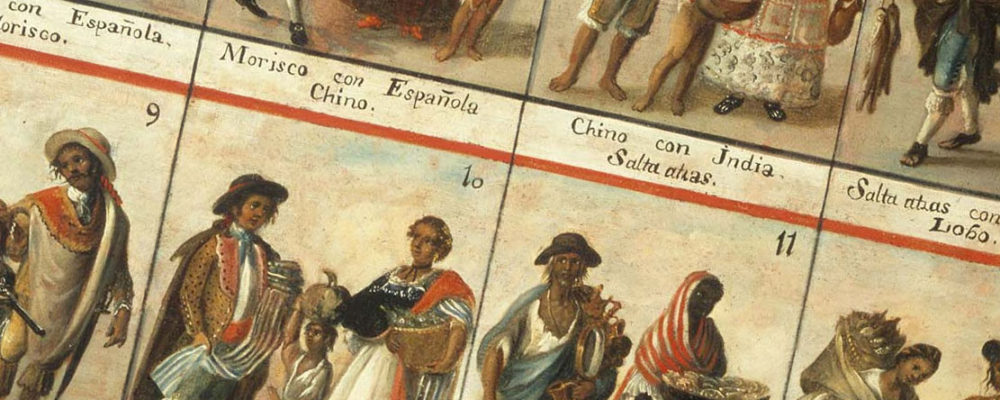

Unknown artist, “Las Castas,” Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlan, Mexico, via Wikimedia.

The elaborate Sistema de Castas painting reveals one of the less-discussed effects of Spanish conquest: sexual liaisons and their progeny. Casta paintings illustrated the varying degrees of intermixture between colonial subjects, defining them for Spanish officials. Race was less fixed in the Spanish colonies, as some individuals, through legal action or colonial service, “changed” their race in the colonial records. Though this particular image does not, some casta paintings attributed particular behaviors to different groups, demonstrating how class and race were intertwined.