Introduction

World War I (“The Great War”) toppled empires, created new nations, and sparked tensions that would explode across future years. On the battlefield, its gruesome modern weaponry wrecked an entire generation of young men. The United States entered the conflict in 1917 and was never the same. The war heralded to the world the United States’ potential as a global military power, and, domestically, it advanced but then beat back American progressivism by unleashing vicious waves of repression. The war simultaneously stoked national pride and fueled disenchantments that burst Progressive Era hopes for the modern world. And it laid the groundwork for a global depression, a second world war, and an entire history of national, religious, and cultural conflict around the globe. These sources reveal some of that tumultuous history.

Documents

1. Woodrow Wilson Requests War (April 2, 1917)

In this speech before Congress, President Woodrow Wilson made the case for America’s entry into World War I.

2. Alan Seeger on World War I (1914; 1916)

The poet Alan Seeger, born in New York and educated at Harvard University, lived among artists and poets in Greenwich Village, New York and Paris, France. When the Great War engulfed Europe, and before the United State entered the fighting, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion. He would be killed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. His wartime experiences would anticipate those of his countrymen, a million of whom would be deployed to France. Seeger’s writings were published posthumously. The first selection is excerpted from a letter Seeger wrote to the New York Sun in 1914; the second is from his collection of poems, published in 1916.

3. The Sedition Act of 1918 (1918)

Passed by Congress in May 1918 and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, the Sedition Act of 1918 amended the Espionage Act of 1917 to include greater limitations on war-time dissent.

4. Emma Goldman on Patriotism (July 9, 1917)

The Anarchist Emma Goldman was tried for conspiring to violate the Selective Service Act. The following is an excerpt from her speech to the court, in which she explains her views on patriotism.

5. W.E.B DuBois, “Returning Soldiers” (May, 1919)

In the aftermath of World War I, W.E.B. DuBois urged returning soldiers to continue fighting for democracy at home.

6. Lutiant Van Wert describes the 1918 Flu Pandemic (1918)

Lutiant Van Wert, a Native American woman, volunteered as a nurse in Washington D.C. during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Here, she writes to a former classmate still enrolled at the Haskell Institute, a government-run boarding school for Native American students in Kansas, and describes her work as a nurse.

7. Manuel Quezon calls for Filipino Independence (1919)

During World War I, Woodrow Wilson set forth a vision for a new global future of democratic self-determination. The United States had controlled the Philippines since the Spanish-American War. After World War I, the U.S. legislature held joint hearings on a possible Philippine independence. Manuel Quezon came to Washington as part of a delegation to make the following case for Filipino independence. It would be fifteen years until the United States acted and, in 1935, Manuel Quezon became the first president of the Philippines.

Media

Boy Scout Charge (1917)

In this 1917 photograph, The Boy Scouts of America charge up Fifth Avenue in New York City in a “Wake Up, America” parade to support recruitment efforts. Nearly 60,000 people attended this single parade.

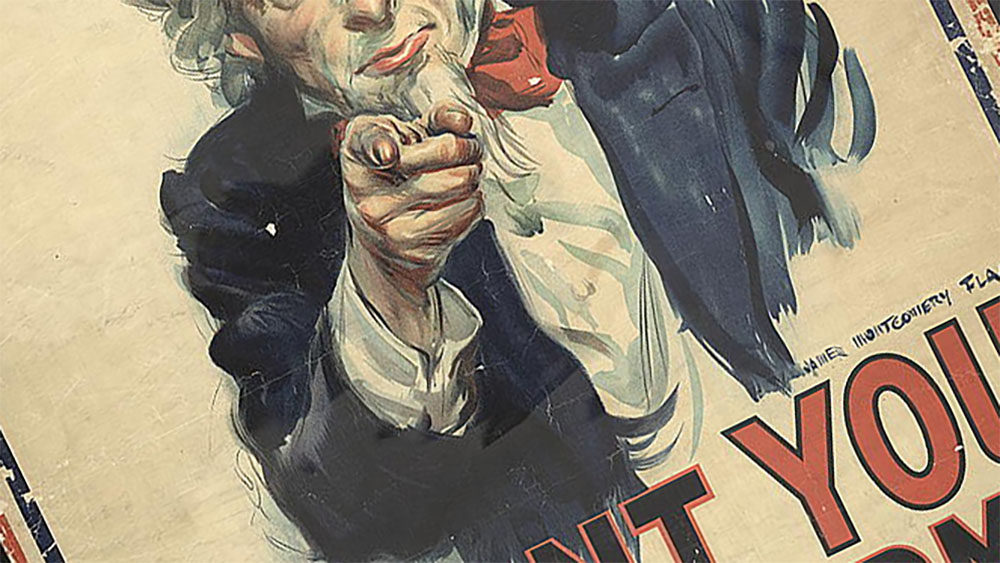

“I Want You” (1917)

In this war poster, Uncle Sam points his finger at the viewer and says, “I want you for U.S. Army.” The poster was printed with a blank space to attach the address of the “nearest recruiting station.” Click on the image to view the full poster.