Introduction

The early nineteenth century was a period of great optimism, with the possibilities of self-governance infusing everything from religion to politics. Yet it was also a period of great discord, as the benefits of industrialization and democratization increasingly accrued along starkly uneven lines of gender, race, and class. Westward expansion distanced urban dwellers from frontier settlers more than ever before, even as the technological innovations of industrialization—like the telegraph and railroads—offered exciting new ways to maintain communication. The spread of democracy opened the franchise to nearly all white men, but urbanization and a dramatic influx of European migration increased social tensions and class divides. Americans looked on these changes with a mixture of enthusiasm and suspicion, wondering how the moral fabric of the new nation would hold up against emerging social challenges. Increasingly, many turned to two powerful tools to help understand and manage the various transformations: spiritual revivalism and social reform. These sources illustrate how religion and reform encouraged Americans to dream of a better nation and a better world.

Documents

Charles Grandison Finney left a successful law practice when he believed God called him to become a preacher. He enjoyed great success, particularly in Upstate New York, a region that Finney called “the burned over district.” Finney’s revivals emphasized human action, and he encouraged his converts to join various reform organizations, including avoiding alcohol and eventually opposing slavery.

Dorothea Dix worked as an educator and author until she took up the campaign for improving the treatment for the mentally ill. Struggling with depression and other mental illnesses herself, Dix presented this petition to the Massachusetts state legislature after visiting a number of jails to chronicle abuses.

David Walker was the son of an enslaved man and a free Black woman. He traveled widely before settling in Boston where he worked in and owned clothing stores and involved himself in various reform causes. In 1829, he wrote the remarkable Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. In it, he exposed the hypocrisies of American claims of freedom and Christianity, attacked the plan to colonize Black Americans in Africa, and predicted that God’s justice promised violence for the enslaving United States.

William Lloyd Garrison participated in reform causes in Massachusetts from a young age. In the 1820s he advocated Black colonization in Africa and the gradual abolition of slavery. Reading the work of Black northerners like David Walker changed his mind. In 1831, he created a newspaper, called The Liberator. The following is the opening essay that Garrison used to explain the purpose of his paper.

Women were active participants in every aspect of the abolitionist movement. In this document, Angelina Grimké, a former Southerner herself, attempts to persuade Southern women of the immorality of slavery. This tactic, called moral suasion, directed the efforts of abolitionists, especially in the 1830s and 1840s.

Antebellum Americans increasingly confined middle-class white women to the home, where they were responsible for educating children and maintaining household virtue. Yet women used these ideas to become more active in the public sphere than ever before, taking prominent roles in all the major reform causes of the era. Women’s participation in the antislavery crusade most directly inspired specific women’s rights campaigns. In this document, Sarah Moore Grimké calls for equality between men and women.

The Transcendentalist movement began in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1836, when a group of Unitarian clergymen formed what later became known as the Transcendental Club. The club met for four years and quickly expanded to include numerous literary intellectuals. Among these were the author Henry David Thoreau. In 1845, Thoreau took up residence at Walden Pond and began to write. The result was Walden, which touted simple living, communion with nature, and self-sufficiency.

Media

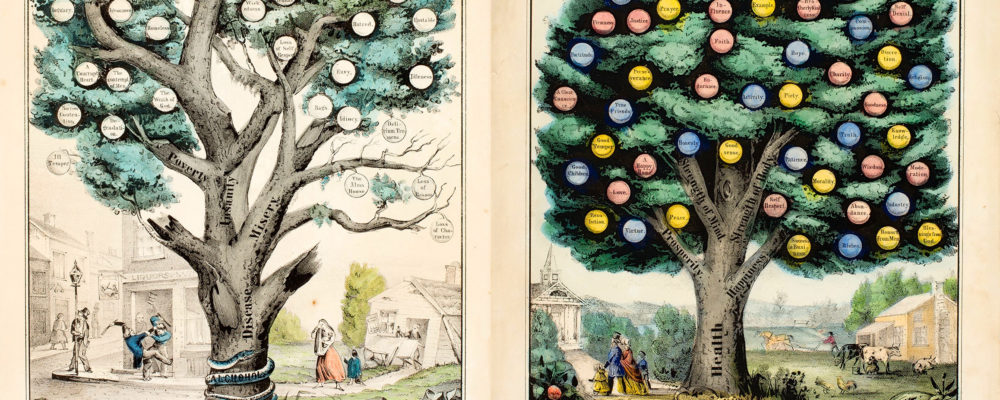

This pair of lithographs, created by Nathaniel Currier (later of Currier & Ives fame), contrasts the “fruits” of abstaining from alcohol to those of indulging in strong drink. It leaves little to the imagination. Intemperance is symbolized by a diseased tree, surrounded by drunks outside of a pawn shop and a woman and her children being thrown out of their home. The lush foliage of temperance, on the other hand, is surrounded by prosperous church-going farm families.

The Second Great Awakening moved American evangelicals to proselytize at home and abroad. The image on this lifetime membership certificate to a missionary society shows how the new member’s money will be used. The guiding hand of Providence and an angel bearing a book (presumably a Bible) hover at the top of the image. In the background, a mosque topples over. An African family kneels and reaches towards the heavens on the left side, while a minister preaches to Native Americans gathered before him on the right.