Introduction

In the early years of the nineteenth century, Americans’ endless commercial ambition—what one Baltimore paper in 1815 called an “almost universal ambition to get forward”—remade the nation. Steam power, the technology that moved steamboats and railroads, fueled the rise of American industry by powering mills and sparking new national transportation networks. More and more farmers grew crops for profit, not self-sufficiency. Vast factories and cities arose in the North. As northern textile factories boomed, the demand for southern cotton swelled, and the institution of American slavery accelerated. The market revolution sparked not only explosive economic growth and new personal wealth but also devastating depressions—“panics”—and a growing lower class of property-less workers. Many Americans labored for low wages and became trapped in endless cycles of poverty. Although northern states gradually abolished slavery, their factories fueled the demand for slave-grown southern cotton that ensured the profitability and continued existence of the American slave system. And so, as the economy advanced, the market revolution wrenched the United States in new directions as it became a nation of free labor and slavery, of wealth and inequality, and of new promise and peril. These sources illustrate how the market revolution transformed how Americans worked, traveled, politicked, and even loved.

Documents

After the War of 1812, Americans looked to strengthen their nation through government spending on infrastructure, or what were then called internal improvements. In his seventh annual address to congress, Madison called for public investment to create national roads, canals, and even a national seminary. He also called for a tariff, or tax on certain imports, designed to make foreign goods more expensive, giving American producers an advantage in domestic markets.

Basil Hall, a British visitor traveled along the Erie Canal and took careful notes on what he found. In this excerpt, he described life in Rochester, New York. Rochester, and other small towns in upstate New York, grew rapidly as a result of the Erie Canal.

The factories and production of the Market Revolution eroded the wealth and power of skilled small business owners called artisans. This indenture contract illustrated the former way of doing things, where a young person would agree to serve for a number of years as an apprentice to a skilled artisan before venturing out on his own.

Maria Stewart electrified audiences in Boston with a number of powerful speeches. Her most common theme was the evil of slavery. However, here she attacks the soul-crushing consequences of racism in American capitalism, claiming that the lack of social and economic equality doomed Black Americans to a life of suffering and spiritual death.

Rebecca Burlend, her husband, and children emigrated to Illinois from England in 1831. These reflections describe her reaction to landing in New Orleans, sailing up the Mississippi to St. Louis, and finally arriving at her new home in Illinois. This was her first experience encountering American slavery, the American landscape, and the rugged living conditions of her new home.

The social upheavals of the Market Revolution created new tensions between rich and poor, particularly between the new class of workers and the new class of managers. Lowell, Massachusetts was the location of the first American factory. In this document, a woman reminisces about a strike that she participated in at a Lowell textile mill.

The French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville travelled extensively through the United States in gathering research for his book Democracy In America. In this excerpt, he described the belief that American men and women lived in “separate spheres:” men in public, women in the home. This expectation justified the denial of rights to women. All women were denied political rights in nineteenth century America, but only a small number of wealthy families could afford to remove women from economic production, like de Tocqueville claimed.

Media

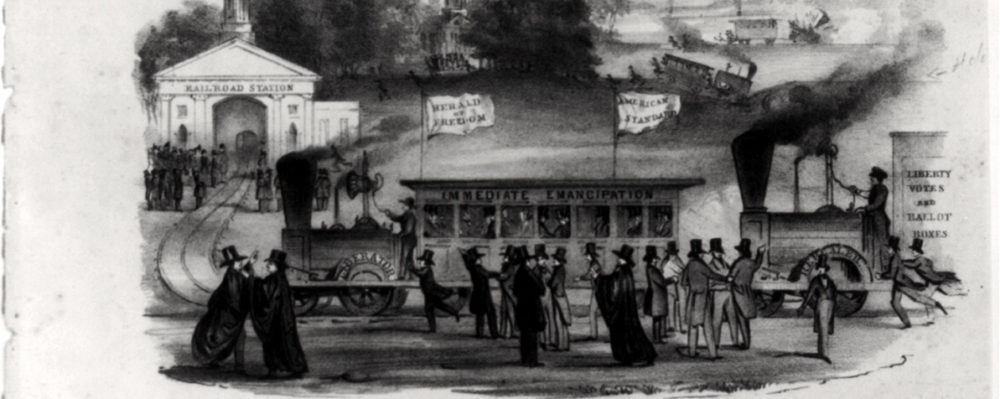

Jesse Hutchinson and B.W. Thayer & Co, “’Get off the track!’ A song for emancipation, sung by The Hutchinsons,” 1844, via Library of Congress.

Irish immigration transformed American cities. Yet many Americans greeted the new arrivals with suspicion or hostility. Nathanial Currier’s anti-Catholic cartoon reflected the popular American perception that Irish Catholic immigrants posed a threat to the United States.

![This anti-Catholic print depicts Catholic priests arriving by boat and then threatening Uncle Sam and a young Protestant boy who holds out a Bible in resistance. N. Currier, “The Propagation Society, More Free than Welcome,” 1855, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003656589/. An anti-Catholic cartoon, reflecting the nativist perception of the threat posed by the Roman Church's influence in the United States through Irish immigration and Catholic education. The invading Catholics have speech bubbles which say, "Only let us get a good foothold on the soil and we'll burn up those [uncldar] and elevate this country to the same degree of happiness and prosperity to which we have brought Italy, Spain, Ireland, and many other lands." "Soverign pontiff say that if his friends have any money when he dies, they may purchase a hole for him in my cemetery at a fair price." "I cannot bear to see that boy with that horrible book [the Bible]" "Go ahead Reverend Father, I'll hold our boat by this sprig of shamrock." "My friend we have concluded to take charge of your spiritual welfare and your temporal estate, so that you need not be troubled with the care of them in future, we will say your prayers and spend your money while you live and bury you in the Potters Field when you die. Revel then, and kiss our big toe in token of submission. The boy and man on the shore respond, "You can neither coax nor frighten our boys, Sir! We can take care of our own worldly affairs and are determined to know nothing but this book [the Bible] to guide us in spiritual things." The man adds, "No you don't Mr. Pope! You're altogether [unclear] but you can't put the mark of the beast on Americans!"](https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/wp-content/uploads/headernoborders.jpg)

![This anti-Catholic print depicts Catholic priests arriving by boat and then threatening Uncle Sam and a young Protestant boy who holds out a Bible in resistance. N. Currier, “The Propagation Society, More Free than Welcome,” 1855, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003656589/. An anti-Catholic cartoon, reflecting the nativist perception of the threat posed by the Roman Church's influence in the United States through Irish immigration and Catholic education. The invading Catholics have speech bubbles which say, "Only let us get a good foothold on the soil and we'll burn up those [uncldar] and elevate this country to the same degree of happiness and prosperity to which we have brought Italy, Spain, Ireland, and many other lands." "Soverign pontiff say that if his friends have any money when he dies, they may purchase a hole for him in my cemetery at a fair price." "I cannot bear to see that boy with that horrible book [the Bible]" "Go ahead Reverend Father, I'll hold our boat by this sprig of shamrock." "My friend we have concluded to take charge of your spiritual welfare and your temporal estate, so that you need not be troubled with the care of them in future, we will say your prayers and spend your money while you live and bury you in the Potters Field when you die. Revel then, and kiss our big toe in token of submission. The boy and man on the shore respond, "You can neither coax nor frighten our boys, Sir! We can take care of our own worldly affairs and are determined to know nothing but this book [the Bible] to guide us in spiritual things." The man adds, "No you don't Mr. Pope! You're altogether [unclear] but you can't put the mark of the beast on Americans!"](https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/wp-content/uploads/cropped-1000x398.jpg)